Welcome to the Keweenaw Historic GeoTrail!

This twenty cache trail will lead you on an adventure through Keweenaw National Historical Park and many of its partner Heritage Sites. We hope you enjoy the beautiful sights as you explore the copper mining history, connect with the people involved, and discover the unique geology that made it possible. Click or scan the QR code to get your Keweenaw Historic GeoTrail passport.

Overview Map

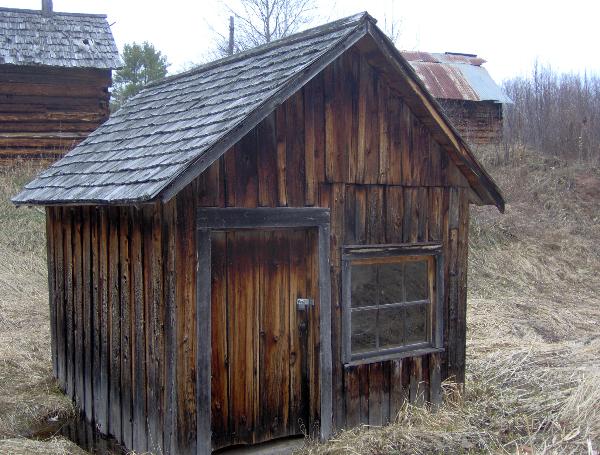

Though the Finnish influence is everywhere in the western Upper Peninsula, pure Finnish survivals are rare. Probably the most remarkable is this self-sufficient homestead farm on a beautiful, remote hillside near the Keweenaw Peninsula's base. Its farmhouse and nine outbuildings are carefully crafted Scandinavian log construction. The Hanka farm has been restored to the way it was in its prime in 1920, when it was the home of Herman Hanka, a disabled miner, his wife, and their four adult children. On the farm they continued the Old World ways they had brought with them to the U.S.

(Photo by sweetlife)

(Photo by sweetlife)

By the time you get to the Hankas' place, you've gone down five miles of country road from U.S. 41 toward Otter Lake; turned at a fire tower near the top of long, high Askel Hill; and driven down a rugged gravel road through a mile of forest. It's quite remote from the outside world, just as the Finns were who homesteaded in this neighborhood in the 1890s. The log house (now a century old), two-story log barn, sauna, and other small outbuildings sit in an 18-acre clearing, surrounded by forest. The Huron Mountains are blue in the distance across nearby Keweenaw Bay. The scene looks like something you'd expect to find in a remote hollow of the Smoky Mountains

(Photo by sweetlife)

One mainstay of self-sufficient local economies like these was cooperation. Neighbors traded and shared harvest work and other skills and products. The disabled father, Herman Hanka, tanned hides and made shoes for neighbors. His son Jalmar tinkered and fixed things; in the early days of automobiles he became a local legend as a self-taught auto mechanic. The family boarded logging horses, which needed intermittent rest between periods of strenuous work. In winter Jalmar and his brother Nik, the farm manager, worked in logging camps, where their sister, Mary, cooked. One neighbor went to town every Saturday to shop for the neighborhood.

(Photo by sweetlife)

People raised their own grains and vegetables, kept chickens and sometimes a pig. The Hankas depended on the Jersey cow and her rich milk for butter and cheese. And they hunted rabbits, partridges, and deer. Such a short growing season (an average of 85 frost-free days) made farmers focus on cold-resistant root crops like turnips, rutabagas, and potatoes. Preserving and preparing food took up an immense amount of time. Social life consisted of the weekly Saturday sauna, visiting, and music. Nik played a homemade kantele, a kind of zither that's the Finnish national folk instrument. Occasional dances were held at a pavilion that stood near where the fire tower is.

(Photo by sweetlife)

Finland's shifting 19th-century economy had transformed many independent farmers into a class of industrial workers and landless tenants without opportunities. Only the oldest son could hope to farm his own land. Finns emigrated to the northern U.S., and many found work in mines. Inexperienced as miners, they did the lower-paying work timbering and tramming. Between the peak emigration years of 1899 and 1914, over 200,000 Finns came to the U.S., largely from two rural counties, Vaasa and Oulu. On the edges of Upper Peninsula mining towns, miners also farmed smaller plots to support their large families. It was a big step up from working in the dark, dangerous mines to buying a 40-acre farm under the Homestead Act and becoming a full-time farmer.

(Photo by sweetlife)

For farms like the Hankas,' everything changed in the 1920s. New sanitation policies allowed the sale only of Grade A milk, which had to be produced and cooled under super-sanitary, refrigerated conditions. Grade B milk produced at farms like theirs could be sold only as cheese. Phone service in this remote neighborhood, unreliable to begin with, became so expensive as the population shrank that customers dropped it and lines were removed. Forests reclaimed many fields. Sons went into the army and saw a bigger world. Beginning when the 1913 copper miners' strike disrupted mining, many Finns went to work in Detroit's auto factories, like Mary's son, Arvo. Henry Ford's five-dollar day only hastened the exodus. Detroit even had a Finnish neighborhood around Livernois and Six Mile. The emigrant children came back to the U.P. only to retire.

(Photo by sweetlife)

The Hanka farm stopped being improved in 1923, when Nik, its energetic manager, died. Gradually most of the Hankas died off, but easygoing Jalmar lived on here until his death in 1966. His needs were simple, and he didn't have the ambition to modernize. The farm pretty much remained a time capsule of old Finnish folkways