This EarthCache is the first in an EarthCache Trail running from Coal Banks Landing (RM 41.5) to Judith Landing (RM 88.5), along the White Cliffs section of the Upper Missouri River. RM is ‘River Mile’. Only this first cache is reachable by car—the remainder can ONLY be accessed from the river, and are intended for those floating the Upper Missouri who are looking for a fun and educational geology-scavenger hunt adventure. This 47-mile stretch, which typically requires three days and two nights to float in a canoe or kayak, is located within the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument/Wild and Scenic River. The Wild and Scenic designation is 149 miles long, from Fort Benton down to Kipp Recreation Area. This entire section of the Missouri is a Class I river, with no significant or dangerous rapids. However, the rest of the EarthCaches in the trail have a 5-star difficulty because the float requires special equipment (boat, tent, stove, etc.), camping experience and planning ahead. Otherwise, once on the river the EarthCaches in this trail are very doable and accessible. Children can certainly come along.

As you travel down the Wild and Scenic Upper Missouri, you will have the opportunity to view firsthand the last undammed portion of this great river, which features outstanding scenery, fascinating geology, and unique plants and animals. The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument plays host to a rich cultural history, including Lewis and Clark campsites, Native American heritage areas, old fur trade posts, steamboat landings, and homestead sites. Without a doubt, floating this segment of the Upper Missouri River is one of the premier canoe trips in North America. For more information on planning a float down the river, please call the Missouri Breaks Interpretive Center (406-622-4000) or visit the BLM website.

For the next EarthCache in the trail, click here.

There is also a series of EarthCaches for the lower section of the river, from Judith to Kipp Recreation Area and for the upper section of the river, from Fort Benton to Coal Banks. For this lower section EarthCache trail, click here.

For this upper section EarthCache trail, click here.

----------------------

Igneous Rocks and Shonkinite

This EarthCache involves floating by a few landforms that are clearly visible from the water. There’s no need to get out of your canoe. At river mile 52, (N 47º58.472, W 110º06.429) four miles before Eagle Creek campsite, you will notice Pilot Rock, a prominent feature on river left. Between 1860 and 1890, steamboat captains depended on this notable rock formation as a landmark while navigating. The ranch house that stands next to Pilot Rock is still managed by members of the same family that homesteaded the land over 100 years ago. There is a small pull-off and some interpretive signs about farming and the homeowners here, but the feature itself is on private land so please respect that and do not trespass to get a closer look (plus you’ll have plenty of opportunities to see igneous rock later).

As you may have noticed, Pilot Rock differs greatly compared to the surrounding rock, which is all sedimentary rock, laid down by the inland sea that once covered much of Montana. This is because Pilot Rock is an outcrop of igneous rock. Igneous rocks are those that have solidified from magma, or extremely hot molten (liquefied) rock. Magma is less dense than solid rock because it is hotter, so its molecules are less densely packed, and it often contains volatiles and gas too. This density contrast to the surrounding rock makes magma buoyant, causing it to rise through the Earth’s crust (the outermost solid “shell” of the Earth). If magma makes its way to the surface, it is called lava. But not all magma finds its way to the surface to erupt as lava. Magma that cools at depth is called an igneous intrusion, because the magma had to force its way through and “intrude” into the existing rock.

But why do rocks melt in the first place? Well, just like a block of ice, when a rock is heated to its melting temperature it turns to a liquid. Only compared to ice, a rock must be very, very hot to melt. It depends on the composition, but most rocks become molten at temperatures between 700-1200ºC (1300-2200ºF). You can actually take any rock into a lab, heat it up, and watch it turn into molten rock at a specific temperature. In nature, though, rocks melt when they are closer to the center of the Earth (the core), which is very hot, on the order of 5430ºC (9800ºF). The majority of this heat is heat derived from radioactive decay of unstable radioactive isotopes (potassium, uranium, and thorium), which shoot off heat energy in the form of neutrons (For more detailed information on why the Earth’s core is hot, see this Wikipedia page). The rate at which temperature increases with depth in the Earth is called the geothermal gradient. The geothermal gradient is approximately 22.1ºC per km, or 1ºF per 70 feet. The geothermal gradient is the reason why mine shafts get hotter as they descend into the ground and travel closer to the Earth’s hot core.

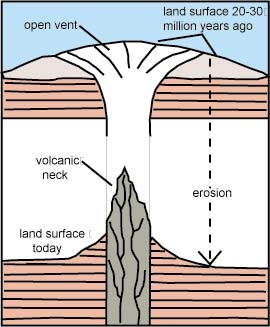

Volcanic plugs are a common intrusive formation here in the Missouri Breaks National Monument. Volcanic plugs (also known as volcanic necks) form when magma rising in a vent towards the surface cools and solidifies, creating a mass of igneous rock. Since igneous rock is hard and resistant to weathering, over time erosion wears away the surrounding softer sedimentary rock, exposing the volcanic plug and forming a prominent feature on the landscape. Sometimes, these plugs are actually the vent of an ancient volcano. The diagram below illustrates the formation of a volcanic plug through time.

Source: Jack Share, http://www.blogger.com/profile/09068066012491070695

Source: Jack Share, http://www.blogger.com/profile/09068066012491070695

Volcanic plugs in Cameroon (Wikipedia Commons)

Volcanic plugs in Cameroon (Wikipedia Commons)

The igneous intrusions in the Monument formed about 50 million years ago during a period of magmatic activity associated with the formation of the Rocky Mountains. Across central Montana, magma derived from a slab of crust sliding underneath North America at the time rose up through the crust, emplacing bodies of igneous rock and causing deformation in the overlying sedimentary rocks. This resulted in the many “island” mountain ranges in central Montana that we see today, which are distinctly removed from the linear Rocky Mountain Range to the west. These island ranges include the Highwoods, the Bears Paw Mountains, the Little Belts, the Judith Mountains, and the Little Rockies. These mountains of igneous origin are all part of a large geologic region called the Central Montana Alkalic Province.

The volcanic plugs and other igneous intrusions found in the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument actually stem from the same magmatic activity that formed the Central Montana Alkalic Province. The region and its intrusions are of particular interest because many are composed of a rare igneous rock called shonkinite. Shonkinite, named after the local town of Shonkin, MT, is only found in a few places in the world, and eastern Montana is one of them. In addition to its scarcity, what makes shonkinite so special is its unique mineral composition.

Shonkinite is a dark-colored, coarse-grained (meaning it is speckled with visible mineral grains) intrusive igneous rock. Shonkinite varies in color from black to dark gray to greenish, and even tan brown. Despite this wide range of colors, what makes it such a distinct igneous rock are the abundant biotite and augite mineral crystal grains. Biotite is an easily identifiable dark mica mineral, which has a characteristic sheet-like appearance and is very shiny. For you mineralogy experts, in shonkinite these mineral grains are embedded in a matrix of potassium-rich material, mostly feldspathoids (minerals that resemble feldspars, but have a different structure and a low silica content). Quartz and plagioclase fledspar, two common minerals found in other igneous rocks, are notably absent (or present in very low concentrations) in shonkinite.

To claim this cache: Answer the following questions and send the answers using Geocache's messaging tool.

Q. What type of feature lies just ahead on river left at N 47º55.720, W 110º03.665? Make sure you look back upstream after passing it, as the feature is more striking from a downstream perspective. Note that this feature is on private land. Please respect that and do not trespass. Just look at it from the river.

Q. There is another prominent feature at river mile 56 on river right, across from Eagle Creek Campground. What name did explorers give to this feature? Do you think it is made of the same rock as the feature mentioned in the previous question? Why? Is the feature here taller or shorter than the sandstone cliffs beside it? Why do you think that is?