The logging questions can be answered from the areas open to the public; please observe park hours and regulations and all "area closed" signs.

There is no cell reception on Garden Key, plan accordingly. App users may want to download all earthcaches nearby before travel so the cache descriptions are fully available.

FORTIFYING GARDEN KEY

Fort Jefferson is described by most sources as the largest masonry project in the Western Hemisphere and second only to the Great Wall of China. Part of Army Chief Engineer General Joseph Totten's "Third System" of coastal fortifications, the fort consists of over 16,000,000 bricks and took thirty years to build. After Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821, the defense of Florida's coastline and approaches became a top priority for the War Department. The Dry Tortugas were strategically significant -- if they fell into enemy hands, they could control access to the Gulf of Mexico. In 1824, Commodore David Porter scouted the Dry Tortugas to determine whether a naval base could be located there. In his report, he described them as "small sand Islands a little above the surface of the Ocean, on some of which is some low shrubbery, but all are liable to changes from gales of wind." Although he favored the harbor around Garden Key, he concluded that the Dry Tortugas would make a poor location for three reasons: the islands were small, they lacked fresh water, and "it is doubtful if they have solidity enough to bear [a fortification]."

Commodore John Rodgers stopped at the islands in 1829 and was much more upbeat about the possibility of a naval base at the Dry Tortugas due to the excellent harbor. His report was shelved for a while, but in 1844, concerned about Caribbean security, Congress appropriated funds to fortify Key West and the Dry Tortugas. Garden Key was selected as the site for a "bombproof cazerne," to be surrounded by outlying batteries, and Lieutenant Josiah Wright was selected as the lead engineer for the project.

FOUNDATION OF FORT JEFFERSON

When it came time to build the fort, engineers had to work around the fact that Garden Key was not exactly a stable platform. Initial planners had presumed that there was a limestone base under the sand that covered Garden Key. But they found that it actually consisted of sand and coral deposits, not solid rock. While the upper and middle Keys are composed of Key Largo limestone, which is fossilized coral, the lower Keys, including Garden Key, are made of oolitic limestone, basically sand bar deposits. Core samples from United States Geological Survey monitoring wells reveal that the upper 3 feet of Garden Key consists of sand and other debris. The next 50 feet is Holocene limestone (less than 12,000 years old), including head coral and sand pockets; below that is Pleistocene (based on current scientific theory, between 12,000 and 2.5 million years old) Key Largo limestone. The Holocene sediments at Dry Tortugas are mostly uncemented, and the mixture of paleocorals and sands proved an unstable foundation for the construction of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key.

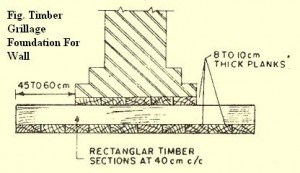

Because of the instability of the sand pockets underlying Garden Key, the engineers decided to use rams to compact the underlying sand and limestone as much as possible, then use "grillages" in building the foundation. Grillages are arrangements of sleeper beams and crossbeams that are used in soft soils to help spread the weight of the structure, compact the ground underneath the foundation, and help reduce the subsidence of the structure. Grillages can only do so much, though; the soil still has to be able to hold the structure. Too much weight, and the soil can shift from underneath the grillages, causing collapse. Although the engineers knew that the weight of Fort Jefferson would cause the building to settle further down into the ground, they hoped that it would settle evenly.

Unfortunately, as construction progressed, it became evident that the weight of the fort slightly exceeded the safe bearing capacity of Garden Key's sand. The fort was not settling evenly, causing cracks in walls and supporting arches. These cracks were continually repaired during the thirty years of Fort Jefferson's construction. But while the cracks above ground could be fixed, other cracks appeared in the cisterns that were part of the fort's foundations. The cisterns were supposed to collect rain water, drained from the roof, and store it for the fort's occupants. As the fort settled unevenly, the cisterns cracked, letting in seawater. As a result, the garrison had to depend on distilling sea water.

Note that other cracks in the brickwork were caused by the iron drain pipes in the walls and the iron shutters in the cannon embrasures (to protect cannon operators against incoming fire), both of which expanded as they corroded. When looking for evidence of the fort's foundation settling unevenly, look in the center of brick archways.

THE BRICKS OF FORT JEFFERSON

In 1850, Lieutenant Wright was sent to Pensacola and Mobile to visit local brickyards and to determine which ones were capable of supporting the Fort Jefferson project. Wright wanted to make sure the bricks would be durable in the marine environment, so he visited Fort Morgan, near Mobile, and Fort Pickens, near Pensacola, to inspect how those brick forts were holding up. He found that Fort Morgan's bricks, produced around Mobile, were deteriorating. However, Fort Pickens, made from bricks fired around Pensacola, was in excellent shape. The clay for Fort Jefferson's "Pensacola bricks" came primarily from Escambia County, Florida.

Pensacola brickmaker J.W. McCrary, Sr., scouted the area until he found his preferred "fire clay." This "homogenous primitive clay," as he described it, was located in an area around the Perdido River, in beds from six to forty feet thick. Government contracts were drawn for an initial order of 3 million bricks for Fort Jefferson and specified that Escambia clay be used. When clay bed owners along Florida's Blackwater River heard this, they protested, so the contract was modified to allow Escambia clay or clay of equal quality. Subsequent testing, however, revealed that the Escambia clay outperformed the Blackwater clay. So, construction began using sandy colored Escambia clay bricks.

Construction on Fort Jefferson continued at a relatively constant pace through the 1850s, with pauses here and there caused by the odd hurricane or by Congress's occasional failure to allocate yearly funds. But when Southern states began to secede after Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, Fort Jefferson's brick supply suffered. As early as January 5, 1861, Pensacola brickyards hinted that they would not supply bricks for "Yankee forts" if Florida seceded from the Union. Florida did secede five days later, and the brickyards abrogated their contracts on February 28, 1861.

Needing more bricks, engineers on the Fort Jefferson project turned to brickyards in Danvers, Massachusetts, and Brewer, Maine. These "Northern bricks" had initially been considered for Fort Jefferson, but prior to secession it was deemed more cost effective to procure local bricks rather than ship them down the Atlantic coast. Now the builders had no choice: it was these bricks or nothing, and they needed to ensure Fort Jefferson would be able to defend itself if Confederate forces attacked.

A quick glance reveals that the "Northern bricks" look nothing like the "Pensacola bricks" -- they are different sizes and colors. The soil for the "Pensacola bricks" comes from Escambia clay deposits, consisting of yellowish clay with a higher granular consistency and weak iron oxide content. The "Northern bricks" were made from clay with higher iron oxide content and less granular consistency. Even though the "Pensacola bricks" outshone "Mobile bricks" during testing, ironically, they do not seem to weather as well as the "Northern bricks."

CEMENT AND CONCRETE

To make the foundation and hold the bricks together, engineers needed something that would set in the wet environment. They turned to natural cement from Rosendale, New York. Natural cement is hydraulic cement made from limestone that has high clay content (argillaceous limestone). It is different from building lime, which is made from limestone with lower clay content, in that lime is not hydraulic (does not set under water). Lime and natural cement are both produced by heating limestone to approximately 900 to 1100 degrees Celsius, at which point carbon dioxide bound within the stone is released. But lime can't set in water -- it has to be exposed to carbon dioxide and can take weeks or months to cure and harden. Natural cement, however, will set when mixed with water, and hardens through a process of cement hydration. Rosendale cement was therefore used both as mortar for the bricks and, when mixed with sand and coral taken from nearby keys, to make the concrete for the fort's foundations. (Sand from the other keys was also used to fill in the ground inside the fort's walls -- Garden Key originally had a depression with a brackish pond in the center of the island, but this has long been filled in.) The coral used for aggregate in the concrete is clearly visible around the fort, especially in the roofs of the magazines on the top of the walls.

LOGGING THIS EARTHCACHE

To log this earthcache, email us or send us a message and copy and paste these questions, along with your answers. Please do not post the answers in your log, even if encrypted. There's no need to wait for confirmation from us before you log, but we will email you back if you include your email address in the message. Group answers are fine; just let us know who was with you.

1. The name of this earthcache: Castle in the Sand: Building Fort Jefferson.

2. Examine the brick arches as you walk through the fort for structural cracks caused by the foundation settling at different rates. Note where you saw cracks and how long and how wide the cracks are (no need for feet or inches, just describe relative to what you see). Did you see any repairs made to the cracks, and if so, do the repairs appear to be working?

3. Go to the top of one of the stairwells, where you can view both the yellow "Pensacola bricks" and red "Northern bricks" next to one another. Describe the differences you see between the two types of brick. How have the bricks weathered differently? (PLEASE NOTE: We're not asking about any bricks that have fallen, we're asking how the bricks that are still in the wall have held up to the elements.)

4. Examine the cement roof of one of the magazines on top of the walls. How many kinds of coral can you identify? (If you don't know the names, just describe the shapes of coral you see.)

Photos of your visit are always appreciated, but please do not post photos of any cracks or closeup photos of the brick or concrete surfaces.

SOURCES

Richard A. Davis, "Dry Tortugas National Park. Ann G. Harris et al, ed., Geology of National Parks Vol. 2 (2004).

Edwin C. Bearss, "Historic Structure Report, Historic Data Section, Fort Jefferson: 1846-1898, Fort Jefferson National Monument, Monroe County, Florida." National Park Service (1983).

Louis Anderson, "Historical Structure Report, Architectural Data Section, Fort Jefferson National Monument, Florida." National Park Service (1988).

Scott Kirkland, "Just Add Water." National Parks Magazine, Winter 2009.

Ted Cushman, "Restoring An Island Fortress Brick By Brick." Journal of Light Construction, May 2011.

"Soil Survey of Escambia County, Florida." U.S. Department of Agriculture (2004).

This earthcache was placed with the permission of the National Park Service.