Location: Glastonbury,Connecticut N

41o 42.8657’, -072o28.1802’

(parking area)

Date listed:

Waymark Code:

Listed by: CTGEOSURVEY

Purpose: This EarthCache is created by the Connecticut

Geological and Natural History Survey of the Department of

Environmental Protection. It is one in a series of EarthCache

sites designed to promote an understanding of the geological and

biological wealth of the State of Connecticut.

Directions: From Route 2: take exit 8 to route 94

east. Follow Hebron Ave (rte. 94) eastward for 6.5

miles. Turn left (north) onto Birch Mountain Road.

Follow Birch Mountain Road 0.5 (one-half) mile north to a gate,on

the left, for a utility company’s right-of-way (ROW) access

road under the power lines. Park near the gate to start the

Earth Cache.

Long Description: The following directions will guide you

to your first destination at coordinates N.

41o 43.0398’, -072o

28.4693’. Pass around the gate and follow the

dirt roadwest. As the road winds (it will cross the newly

relocated Shenipsit Trail at marker #56), an outcrop will come into

view. Continue to follow the road as itloops around and to

the top of the outcrop.  The road will continue west while a

trail (the old Shenipsit Trail) continues north into the woods

. Follow the trail north about 250 yards (it runs parallel to

a stone wall in the distance to the west which you may not be able

to see when the trees are vegetated). The trail will lead you

to the coordinates above where it intersects with the blue-blazed

(relocated) Shenipsit Trail. Arriving at your location large

boulders should be in plain sight (Figure 1, the Shenipsit Trail

passes between the boulders). Walk around them and take a good

look. They appear to be composed of white, black, and clear

minerals,

The road will continue west while a

trail (the old Shenipsit Trail) continues north into the woods

. Follow the trail north about 250 yards (it runs parallel to

a stone wall in the distance to the west which you may not be able

to see when the trees are vegetated). The trail will lead you

to the coordinates above where it intersects with the blue-blazed

(relocated) Shenipsit Trail. Arriving at your location large

boulders should be in plain sight (Figure 1, the Shenipsit Trail

passes between the boulders). Walk around them and take a good

look. They appear to be composed of white, black, and clear

minerals,

Figure 1. Two largeboulders. Image was taken to

the east of the boulders along the Shenipsit Trail (notice blue

blaze on tree in middle). Boulders are composed of light gray

granitic gneiss.

probably feldspar, biotite, and quartz respectively. The

largest of the boulders (about 8 feet tall) is quite angular.

This would lead us to believe that it has not traveled very

far. As rocks are transported by gravity, water, or a glacier

they become rounded. This is because as they travel, the

edges are chipped away from contact with other rocks. After

you are done examining the rocks, look around at the surrounding

landscape. You are standing at the highest elevation around;

i.e. there are no higher areas near-by from where these rocks could

have rolled. Certainly a torrent of water necessary to move the

boulders would not flow at the top of a hill or ridge. The rest of

the EarthCache will enable you to determine where the boulders came

from and how far they may have traveled.

To find coordinates N. 41o42.9448’,

-072o28.5108’, follow the trail back from

where you came. As you are walking look for other boulders

much smaller in size. The trail passes between two boulders

directly opposite one another just before coming to the ROW.

The larger of the two, which is on your left, is the one of

interest (see Figure 2). Inspect the rock and the area on the

trail in front of it. You should notice that the rock is very

similar in composition to the larger boulders we have already

seen. At the base of the rock we can see that the bedrock on

which the boulder sits and the boulder are of different

lithology. The bedrock is dark gray colored schist of the

Littleton Formation. It is a medium-grained mica schist with

millimeter size garnets and 2.5 cm long staurolite

Figure 2. Boulder of light

gray granitic gneiss sits on top of dark gray mica

schist. Can you find the 15 cm pencil used for scale

(it is standing on its point. Hint: try

enlarging the magnification on your screen??

crystals. The schist was once mud at the bottom of the

Iapetos Ocean. The mud was subjected to intense heat and

pressure and was metamorphosed into this schist. The garnet

and staurolite crystals indicate that there were high amounts of

iron and aluminum present during metamorphism and that the

temperature and pressure during metamorphism was moderate to

high. Continue to follow the trail south and keep your eyes

on the ground. You may see parallel grooves in the bedrock

you are walking on.

As you come out of the woods at the utility company ROW, you

will have reached the spot of the next location. After

enjoying the view, inspect the rock on which you are

standing. Here you will find it easy to see a series of

parallel grooves in the schist bedrock (Figure 3). As you

look around more you see that these lines are quite

extensive. They cover the entire surface of the top of the

bedrock. They can also be found on outcrops in the woods and

down the hill in the ROW.

Figure 3. Glacial

grooves and striations on surface of Littleton Schist at edge of

ROW. Foliation (feet of geologist are on top of weathered

foliation plane) cuts across the rock at almost 60o to

the orientation of the grooves. Glacial groove orientation is

S. 38oE (142o) at this

location.

Notice that the grooves are at an angle to the layering

(schistosity foliation) in the gray Littleton Schist. What could

have created these? Grooves could be etched into the rock

from off road vehicles (and some are present near-by). To be

certain of their origin you may want to walk into the woods again

along the trails to see similar grooves (if you follow the

Shenipsit Trail north about a mile, many outcrops containing

glacial grooves and striations will be crossed). They were

not made by machines. These are called glacial

striations. They are formed when rocks and other debris

frozen into the base of the glacier gouged into the bedrock as they

were being dragged along the bottom of the glacier and ground

up.

Striations indicate the last direction the glacier was

moving: the ice moved parallel to the striation. They

only indicate the last ice flow direction because a change in

direction during the retreat of a glacier may have obliterated

earlier directional indicators. It turns out that these particular

striations and grooves record average ice movement direction during

the ice age.

Figure

4A.

Figure 4B.

Figure

4A.

Chatter marks developed along the

grooves and striations by a large rock(s) frozen into base of

glacier that “bounced” as it gouged into the underlying

ledge (red pocket knife is ~9 cm long [3.5”]). Grooves

are oriented S.38oE (SE is toward top of both A. and

B.)

Figure 4B. Chatter mark

(at point of pen) that may be lunate shaped indicating movement was

toward the SE (top). Cresentic gouges (convex side points in

direction from which the glacier came) indicating SE ice movement

are also reported from the area.

As the striations are linear features, the ice theoretically

could have been moving in either direction. A closer look

(Figure 4) at some of the striations located closest to the power

lines, one may notice that it appears as though some grooves

contain “chatter marks” (see definition in caption for

Figure 4), some of which have been chiseled out into half-moon

shapes (lunate) whose convex side points in the direction toward

which the glacier moved. Toward what direction would the ice

have moved? Movement from the northwest is consistent with

data found in other areas nearby.

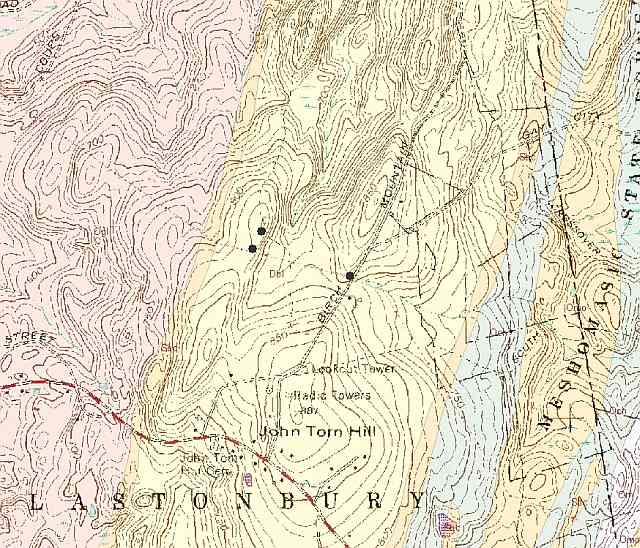

Now we have all the information we need to

infer the origin of the large boulders we encountered at the

beginning of this exercise. The ice was last moving from the

northwest. The bedrock map of the Marlborough Quadrangle

(Figure 5) shows the Glastonbury Gneiss underlies a large area to

the northwest of our location. The Glastonbury gneiss is a

gray medium-grained gneiss with quartz and feldspar. This

would explain the mineral composition we noted when first examining

the boulders. The closest mapped outcrops of contact between

the gneiss and the schist are ~1/2 km away. A rock that has

been transported by a glacier and is resting on bedrock of

different lithology is known as a glacial erratic. We now

know that the boulders are really glacial erratics that have been

transported at least 1/2 km from their source to the northwest.

Now we have all the information we need to

infer the origin of the large boulders we encountered at the

beginning of this exercise. The ice was last moving from the

northwest. The bedrock map of the Marlborough Quadrangle

(Figure 5) shows the Glastonbury Gneiss underlies a large area to

the northwest of our location. The Glastonbury gneiss is a

gray medium-grained gneiss with quartz and feldspar. This

would explain the mineral composition we noted when first examining

the boulders. The closest mapped outcrops of contact between

the gneiss and the schist are ~1/2 km away. A rock that has

been transported by a glacier and is resting on bedrock of

different lithology is known as a glacial erratic. We now

know that the boulders are really glacial erratics that have been

transported at least 1/2 km from their source to the northwest.

Figure 5. Geologic map

of a portion of the Marlborough Quadrangle showing Birch Mountain

Road. The pink area on the map is underlain by Glastonbury

Gneiss; the areal extent of the Littleton Schist is shown in

yellow; two of the black dots show the GPS-locations of our

observations and the third shows the parking area on Birch Mountain

Road.

How to log this EarthCache:

1.What is the weight of the largest boulder illustrated in

Figure 1? To answer this estimate the volume of the boulder by

estimating its average dimensions (length, width, and height). It

is an irregular shape so this may present a challenge. For instance

the boulder is about 8 feet high at its highest, but the average

height may only be about 6'...or 5 1/2 feet or more or less. Then

multiply the average length times the average width times the

average height. A rule of thumb that stone masons use is that a

stone wall 2' x2' x3' weight about a ton (a ton is 2000 pounds).

So, dividing the volume by 12 should give you the weight of the

stone in tons.

2. Accompany your answer with a picture. First lay your GPS

along one of the striations so that its antenna points in the

direction toward which the glacier moved. Take a picture showing

your GPS unit and the striation. Determine the bearing of that

direction. A measurement is preferred but if you cannot do that

with your instrument chose from the following: E (090°), ESE

(112.5°), SE (135°), SSE (157.5°), S (180°), SSW (202.5°), SW

(225°), WSW (247.5°), or W (270°).

3. Optional: Submit a picture of you or a member of your party

doing this EarthCache if you would like us to post it on our

Geology Webpage at the Connecticut Department of Environmental

Protection. We are particularly interested in developing activities

that families can do together, and want to show that EarthCaches

are a fun way to get outdoors.

Difficulty: 1

Terrain difficulty: 3

References:

Bell, M., 1997, The Face of Connecticut, Connecticut

State Geological and Natural History Survey, p. 124-125.

Bennett, M.R., and Glasser, N. F., 2003, Glacial Geology, Ice

Sheets, and Landforms, 109-115.

Snyder, G.L., 1970, Bedrock Geologic and Magnetic Maps of the

Marlborough Quadrangle East-Central Connecticut (1:24,000), U.S.

Geological Survey Geologic Quadrangle Map GQ-791.

Stone, J.R., Schafer, J.P., London, E.H., DiGiacomo-Cohen, M.L.,

Lewis, R.S. and Thompson, W.B., 2005, Quaternary Geologic Map of

Connecticut and Long Island Sound Basin (1:125,000), United States

Geological Survey Science Investigation Map #2784.

This EarthCache was written by

Earl Manning in 2008 while he was an undergraduate student at

Central Connecticut State University and working part time for the

State Geologic and Natural History Survey of Connecticut. He

enrolled in the Graduate School at the University of Oklahoma in

the Fall of 2009.

The Kongscut Land Trust

graciously gave permission to publish this EarthCache on land under

their stewardship.