Welcome to Bayou Metairie

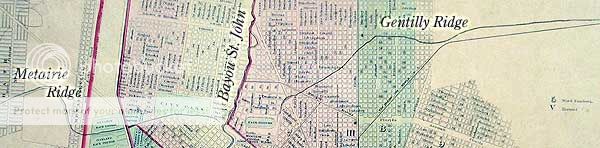

This bayou along the Southern edge of City Park is all that remains of the central portion of an ancient Mississippi River flood channel. This bayou originally began near Kenner, Louisiana, meandered its way eastward across the entire New Orleans area, and ended south of Irish Bayou. Its segments were named Bayou Metairie in the West, Bayou Gentilly in the middle, and Bayou Sauvage in the East. The bayous conferred their names to the banks, or ridges, which Native Americans and settlers used as paths, and eventually roads. Bayou Metairie gave us Metairie Ridge which became present day Metairie Road. Bayou Gentilly, became Gentilly Ridge and finally Gentilly Road and Chef Menteur Highway. The eastern remains of the channel, Bayou Sauvage, are still in existence where Chef Menteur meets Highway 11.

The purpose of this cache is to understand the geologic processes which formed the ridge and its impact on the geography and development of the area.

|

|

Detail of Metairie Ridge, Bayou St. John, and Gentilly Ridge from an 1879 map.

(text in italics added by the author)

|

The River Builds

The Mississippi River is the dominating geologic feature in Southeast Louisiana. It was the river after all which created Southeast Louisiana. Draining 41% of the continental United States, including 31 states and two Canadian provinces, more than 400,000 tons of sediment are carried by the river every day. While the river's course is currently being constrained by the hand of man, it was certainly not always so. The sediment laden river has been overflowing its banks and even changing course over the past 5,000 years. Through which it laid down the land that would eventually become New Orleans. To put the creation of this region into perspective, it was only 4,800 years ago that the first pyramid was built for King Djoser of Egypt. In Geologic terms, New Orleans rests on some of the newest real estate on the planet.

|

|

Mississippi River Deltas over the past 5,000 years.

Sale-Cypremort Delta 5000-4500 years ago

Cocodrie Delta 4500-3500 years ago

Teche Delta 3500-2500 years ago

St. Bernard Delta 2500-1500 years ago

Lafourche Delta 1500-700 years ago

Plaquemines Delta 1200-500 years ago

Balize Delta 500 years ago to present day

|

Over those past 5,000 years, seven major deltas were formed by the Mississippi River. With each change in course, a new location would receive the sedimentary deposits carried down from the upper continent. From 4,500 to 3,500 years ago, the Cocodrie Delta began laying the groundwork (literally), for the land beneath New Orleans and the ridges across the floodplains. Over time, other deltas would come to complete the work. When the river wasn't changing its course the surrounding areas were subject to periodic flooding. Mirroring the sedimentary work of the parent river, the flood waters carried sediments into the surrounding swamps forming meandering distributaries with their own, smaller, river banks.

The French Settle

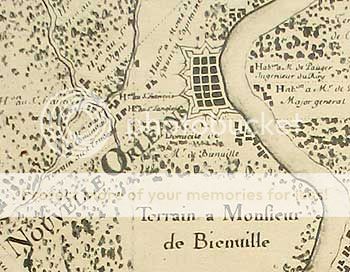

When early French explorers came to the area, the local natives revealed the banks, or ridges, as the paths they used to traverse the swamps. Bayou Road (the oldest road in the New Orleans area) lies on one such ridge. Its ridge, Esplanade Ridge, runs from the river and intersects with Metairie Ridge and Gentilly Ridge at Bayou St. John. When New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean Baptiste le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, he chose the point where Esplanade ridge meets with the river's natural levee.

Backtracking just a bit, it was in 1670, that René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle explored the upper continent and sailed down the Mississippi River to discover its link to the Gulf of Mexico. LaSalle claimed the river and all the land which it drained in the name of France. La Salle returned to France and made the case for the establishment of a fortification and colony on the Mississippi River near the Gulf of Mexico. He reasoned that a military fortification would not only protect France’s claim on the land, but would provide for a safe harbor from which they could harass both the Spanish and British fleets in the Gulf. While LaSalle's return to the region in 1684 was an ill-fated voyage, a subsequent voyage by Pierre le Moyne, sieur d' Iberville and his brother, Bienville, in 1698 had much better luck. Ibverville and Bienville found their way along the Gulf Coast to Lake Ponchartrain and south into Bayou St. John. Led by the local natives, they were shown the way to the Mississippi via the Esplanade Ridge.

While the city could have been located up or down the river from its chosen site, the ridges of the area helped in the selection process. The French needed to protect their claim on the watershed of the Mississippi River. LaSalle's plan called for a fortification on the river. The fortification site would thus need a support colony and lands on which to settle that colony. The wide natural levees of the Mississippi and the banks of its distributaries offered that needed land. To support the colony, it was realized that trade with the city itself would be best served through a shortcut through Lake Ponchartrain, Bayou St. John and down the Esplanade Ridge. Having trade with the city itself move through Lake Ponchartrain rather than the much longer route down the river to the Gulf would be beneficial to the local economy.

|

|

Map Of New Orleans, 1723

(North is to the left)

Note the crossing of Metairie, St. John, and Gentilly Bayous to the left of the fortified city.

|

Lands along Bayou Metairie and Bayou Gentilly were awarded to colonists to help develop the region. One such development was the Allard Plantation, significant in that its land would eventually become the plot for City Park, the location of this cache. Commerce between the city and the agricultural developments and areas outside the city would be facilitated by the ridges. Plantation products and supplies would move in and out of the swamps via the ridge roads.

Ridge Cemeteries

As the City of New Orleans grew, so too did its conflict with the local environment. Drainage of sewerage and rainwater was (and still is) the chief environmental problem which faced the growing city. Early plagues of yellow fever would eventually be tied to mosquitoes and poor drainage, for instance. The need for cemeteries was such that early on, inner city cemeteries would fill and be closed. Locals and tourists note our abundance of above ground crypts. Mistakenly, this is attributed to the city's elevation. It is more a result of the city's Caribbean/Spanish heritage. Such burials are typically too expensive for the remains of the city's poor and indigent dead. Burying the poor required the less expensive method of burial in the ground. Burying anyone in the ground in New Orleans requires well drained soil. Metairie Ridge offered the needed solution.

|

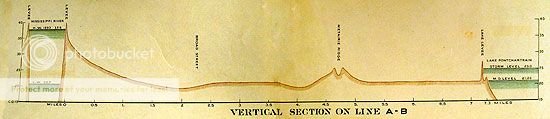

Vertical section of New Orleans, 1894.

Note the double peak of Metairie Ridge.

|

|

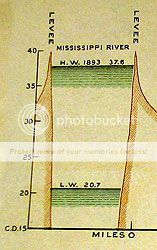

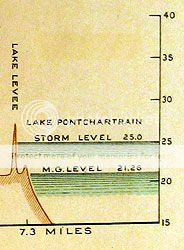

Detail from the above

cross-section.

Note the High and Low levels for the River (left) and Lake (right) with respect to the city between (above).

|

|

The ridge once marked the northernmost developed land in the city. The land beyond the ridge towards Lake Ponchartrain was considered unusable swamp. It was preferred that the indigent dead would not be buried within the city. As Metairie Ridge was on the outskirts of the city on well drained soil it would be chosen as the site for a new pauper's cemetery. In 1879, the Locust Grove Number 1 and 2 cemeteries (on Freret Street) were closed and a new cemetery was opened. Thus we have the second stage of the cache, Holt Cemetery.

|

|

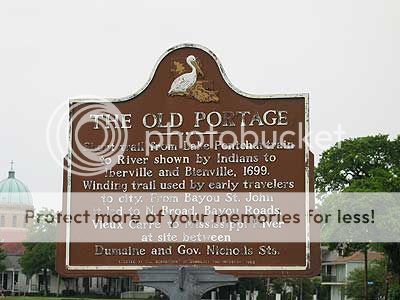

Historical Marker at the intersection of Bayou Metairie, Bayou Gentilly, and Bayou St. John

|

Holt Cemetery is presently 5-6 feet above sea level; some of the highest land in the area. Visit "The Holt" (N 29° 59.067 W 90° 06.345) and you'll notice that the dead are still buried in the ground, not interred in above ground crypts. If you're standing as far back as City Park Avenue, it should be easy to see how much higher the ground is.

|

|

President of the Louisiana State Board of Health for whom Holt Cemetery is named.

|

The Holt is a good place to bust two myths about New Orleans at once. Yes, we can bury our dead in the ground; and No the city is not completely below sea level. Only 60 or so percent of the city is below mean sea level. Land created near the river, like the French Quarter, and areas along the ridges make up much of the remaining 40 percent.

|

|

Marker showing the beginning of the road (portage) used by early settlers to get to the river.

|

Conclusion

As the city grew and dealt with its drainage problems, locations north of Metairie Ridge increased in their usefulness and were settled. Bayous Metairie and Gentilly were finally drained and filled in during the early part of the 20th century. The only evidence which remains in the city are the curiously curved roads and this small stretch of bayou along the southern end of City Park. New Orleans is a metropolis claimed from the wilderness in ways unseen in other parts of the country. While it no longer fortifies France's claim on the upper Mississippi Valley, it still operates as a significant port on the Gulf of Mexico; the realization of the potential seen by LaSalle. However, if it were not for the ridges of this area, Bienville would have been forced to pick a location perhaps not as well suited to the needs of his day or of ours. And, perhaps, the development of Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley would not be what we recognize today.

To claim this cache, you must email me answers to the following:

- At the cache location, turn and face City Park Avenue. 75 feet towards the street, you will see the BACK of an historical marker. What is the title on the BACK of the marker?

- At the entrance to Holt Cemetery (N 29° 59.067 W 90° 06.345), there is a monument (no need to enter the cemetery). What is the last name in the first column of names?

- Do ONE of the following:

- Homework: Tell me how much water flows through the city every second via the Mississippi River? (gallons or cubic feet ok)

- Footwork: Post a photo of yourself and your GPSr with Bayou Metairie in the background.

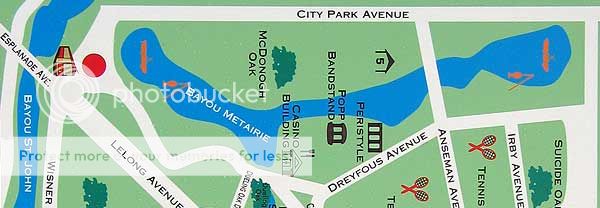

(Note: Bayou Metairie only runs along City Park Avenue; see the map below. All other lagoons in the park are man-made and do not count.)

|

|

Bayou Metairie of City Park

|

Photo Credits:

Metairie and Gentilly Ridges: "Map of the City of New Orleans" J. A. d'Hemecourt, 1879

Cross-Section of New Orleans: "Report on the Drainage of the City of New Orleans, by the Advisory Board", "Plate II, Contour Map Of New Orleans", 1894

Antique Map: "Carte Particuliere Du Flevue St. Louis dix lieües au dessus et au dessous De La Nouvelle Orleans ou sont marqué les habitations et les terrains concedés à Plusieurs Particuliers Au Mississipy" 1723

Dr Joseph Holt: "The City of New Orleans. The Book of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Louisiana", p 173

Bayou Metairie Map: Photo of a "You Are Here" map sign near the cache.

All other photos and graphics created by the author.

Bibliography:

"Report on the Drainage of the City of New Orleans, by the Advisory Board" New Orleans: Geo. W. Englebardt, Publisher 1894

Campanella, Richard "Time and Place in New Orleans: Past Geographies in the Present Day" Pelican Publishing Company 2002

Florence, Robert "New Orleans Cemeteries, Life in the Cities of the Dead" New Orleans: Batture Press 1997

Huber, Leonard V., "New Orleans Architecture #03: The Cemeteries" Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company 1997

Kelman, Ari "A River and Its City, The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans" Berkeley: University of California Press 2003

Lemmon, Alfred E., John T. Magill, Jason R. Wiese "Charting Louisiana, Five Hundred Years of Maps" New Orleans: The Historic new Orleans Collection 2003

The author would like to thank:

-

My father, for pointing me in the direction of this geological feature.

-

Andrew Fox, author of "The Fat White Vampire Blues" and "Bride of the Fat White Vampire", for illustrating New Orleans and specifically Holt Cemetery so well in his novels. Go get these books, they're hillarious.

-

Loyola University New Orleans, Monroe Library, Special Collections Department: For their help and collection of books both old and current.

-

Tulane University, Special Collections Division, Jones Hall: For their help and patience while I poured over some very old maps.

-

New Orleans City Park: For their permission in letting me take you to this interesting site.

-