"Tiger Stadium"

For generations of baseball fans in Metro Detroit and around the world, those two words together weren't just words. They were the name of a place...a "home" for things that were good, wholesome, and relaxing, even for a few hours when their favorite baseball team would play a game that isn't fast-paced, isn't hectic, but does have it's moments that do include those two descriptives. Tiger Stadium was not just a physical building made of brick, mortar, and steel, but it had a heart, a soul, and most definitely a spirit that would be shared and enjoyed by anyone who ever had the privilege to visit and spend time there.

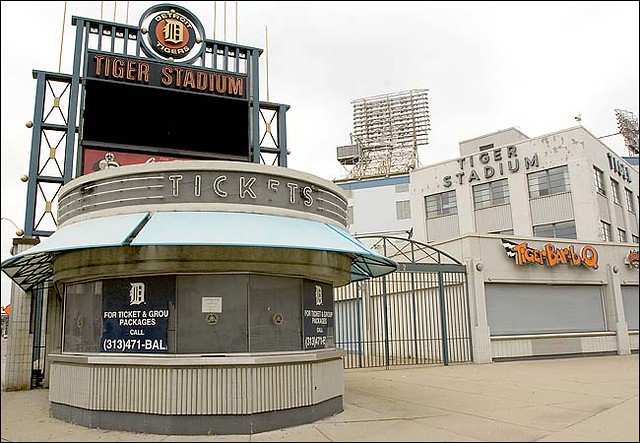

The 'ghost' of Tiger Stadium then...and now only the field and flagpole remain.

The 'ghost' of Tiger Stadium then...and now only the field and flagpole remain.

What remains today... aside from the flagpole and United States flag that adorns it... is the memories, and the spirit, even though the physical building has been removed and the debris taken-away... and of course, the stories.

Before Detroit baseball

was at "The Corner..."

Baseball became an organized and professional sport in the decades following the Civil War and was dependent on the prosperous middle class whose men had the financial means to purchase tickets and had time to spend on watching sporting events.

The Detroit of 1890 was a city with a population of 200,000 people and seemed promising as a site for a professional baseball team, but the Detroit Wolverines, who were a minor-league team and began playing at a park where Harper Hospital now stands (Recreation Park), would later play at a park on East Jefferson near the MacArthur Bridge, known as Boulevard Park. At that time, Detroit had not expanded it's city limits out that far, and the area was more "country" look and feel versus "city neighborhoods" that would occupy the land many years later.

Entrance to Recreation Park (now where Harper Hospital stands)

Entrance to Recreation Park (now where Harper Hospital stands)

There was a great economic depression that hit Detroit hard in the early 1890's as Detroit was a center of manufacturing even at that time. Because of this economic depression, nobody attempted to make a living out of selling tickets to minor-league baseball games through 1892-93 as food and other necessities were much-more important than watching sporting events.

Byron Bancroft Johnson, who was a lawyer and sports writer from the Cleveland, Ohio, area dreamed of organizing a professional league that would challenge the dominance of the now-well-established National League. He created a league comprised of teams from 8 different cities and began searching for folks to manage the teams in those cities.

George Vanderbeck was a baseball entrepreneur who had been successful on the West Coast, even though he had originally been from New York. Vanderbeck was recruited by Johnson to operate a franchise in Detroit and in early 1894 Vanderbeck "set up shop" with the Manager from the Los Angeles Angels baseball team and they settled on a name for the Detroit club before announcing it to the press.

The New Baseball Team that would represent the City of Detroit for the 1894 season was to be named "The Creams", because he was bringing the "cream of the crop" to represent them in League competition.

Vanderbeck's next task was to find a place for his team to play, which wasn't going to be easy. Harper Hospital was expanding by this time and the previous park called "Recreation Park" that the National League team had played in was demolished. Land owners were asking a great deal of money for their properties and it was becoming such an issue that Vanderbeck eventually got fed-up with the search and even threatened to move the team from Detroit to a faraway place such as Fort Wayne (Indiana) or St. Paul (Minnesota), even before one pitch with the new team had been thrown.

He was searching for property that could be easily reached by public transit and personal means and found one to lease at the corner of Champlain and Boulevard streets, now Helen and East Lafayette streets.

Fans peering over the fence at Boulevard Park

Three electric car lines would bring fans to Vanderbeck's new stadium and grandstands would be erected for those fans to sit in. The stadium was close to Belle Isle and the idea was that families that had visited the island to enjoy all it had to offer would reach the mainland (as Belle Isle was only accessible by ferry at that time) and then enjoy a game afterwards. The idea was that fans would be watching his Creams compete against other Western League teams. The 1894 Detroit team began spring training in New Orleans on March 20 and began their exhibition season on March 25. From there, they gradually traveled by train back to Michigan for their home opener in early May of that year.

The 1894 season drew 60,000 fans to League Park which was considered satisfactory in light of the continuing recession that drastically cut employment in Detroit. The team floundered on the diamonds, finishing seventh in the eight team circuit.

Vanderbeck was very dissatisfied with his park as it was because it was very easy for fans to watch the games without paying any admission. The fans would very easily peer over the outfield fences and enjoy the relatively new pastime for free, which went against the business-plan that Vanderbeck had for his baseball team.

He tried to solve this by placing more boards on the fences that were larger and would block the view from outside the park. Fans responded by sitting atop the neighboring roofs on the houses that surrounded the stadium. The practice of sitting on the roofs around a ballpark continues to-this-day at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

There had been a case years prior that involved the then-defunct Detroit Wolverines baseball club and some of the property owners around their park, Recreation Park. These property owners were putting up stands and charging admission to see baseball games and it got so bad that the Wolverines sued one owner of a property, John Deppert, arguing that he was helping steal a "product" (the fans paying admission) and that he should stop doing so. Deppert owned a barn near Recreation Park and put a grandstand on the roof of the barn, then charged fans to see games from that point.

The local court in Detroit ruled against the baseball team and they decided to carry their litigation to the Michigan Supreme Court. On April 22, 1886, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mr. Deppert’s property rights and threw out the claim of the Wolverines. (61 Mich. 63, 27 N. W. 856; 1886) Undoubtedly, Vanderbeck knew about this litigation and concluded there was little he could do to prevent nearby property owners from charging admission to watch the team he owned. The team continued to play poorly in 1895 and, at one point, Vanderbeck fired his manger and installed himself in the dugout in that role.

View of the old Hay Market at Michigan and Trumbull.

Michigan Avenue runs left-to-right and Trumbull fades off to the right.

At the time, the City of Detroit was much more rural and the city had to maintain a Hay Market at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull as those were the days of horse transportation in most cities. These markets were required as all cities had to have large hay marketplaces to feed their (usually) thousands of horses that kept life moving as we knew it back then.

This should not be confused with the Western Farmers Market that was just down the street at 18th and Michigan and was a bit different than the Hay Market in that there was more items than just hay for sale there.

The city decided to sell the property at Michigan and Trumbull, also deciding to move the hay sales to the Western and Eastern Markets. This would open up the property at Michigan and Trumbull in the Corktown neighborhood and Vanderbeck jumped on the opportunity, in hopes to build a new facility for his baseball team to play. The Recreation Park was just too-small and there was just going to be too much trouble in expanding the small park near Belle Isle as there had been trouble trying to get that park built in the first place, not to mention the trouble that ensued in maintaining that facility.

The Protests... 1890's style.

Chief Pontiac

Chief Pontiac was much more of a national hero in the late Nineteenth Century than he is today and the Chief was seen as an ardent anti-British leader who helped to start the process of change that George Washington and the Revolutionaries would eventually accomplish in the last decades of the 1700's.

During the siege of Detroit in the summer of 1763, Chief Pontiac apparently met with his fellow Indian leaders under the oak trees at Michigan and Trumbull to plot strategy and rally battle troops against the British. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on how you look at it now) those historic preservationists of the early 1890s had no more success in preserving the history at this location than the large number who sought to preserve Tiger Stadium a hundred years later at this same spot.

There had been 28 very old and giant Elm trees on the property and historical preservationists protested the removal of the trees from the property citing that Chief Pontiac had conducted a Council of War under one of these trees and that it was, in a way, living-history.

The preservationists didn't stand in the way of progress...and the land was cleared, saving five of the elm trees and a new park to play baseball on was built. The remaining five trees would later be cleared-out around 1900 as it was just too difficult to have a stadium that had these trees included in the field of play.

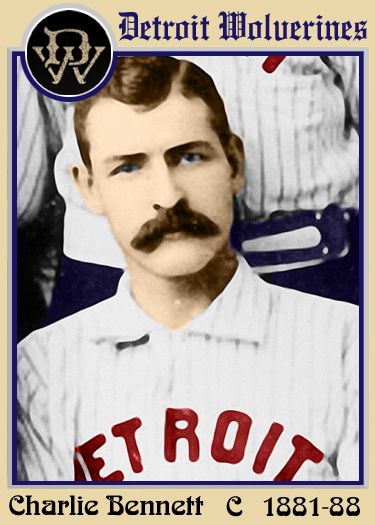

A Charlie Bennett baseball card

A Charlie Bennett baseball card

Charlie Bennett was a popular catcher who played stellar baseball for the Detroit Wolverine National League teams of the 1880s.

There was great sympathy for Bennett since he had been injured in an off-season accident that left him unable to play. In the fall of 1894, Bennett had slipped while boarding a train in Kansas and people watched in horror as the heavy wheels of the moving train took his left foot and crushed his right leg, which later had to be amputated below the knee.

Bennett, a Pennsylvania native who had first played ball in Detroit as sprightly 21-year-old amateur shortstop, returned to the city with artificial legs. To support himself he ran a cigar stand and, in his later years, painted china dishes. Bennett’s dignified response to his tragedy elevated him to near-sainthood status among his many friends, which included almost every person in Detroit.

For three decades, former star catcher Charlie Bennett

For three decades, former star catcher Charlie Bennett

threw out the first pitch before home openers in Detroit.

This one was opening-day of 1915.

Although Bennett repeated the first-toss ritual every spring for the next 30 years, this particular opening day was the most noteworthy of the bunch. It was the first game played at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

It was April 28, 1896, a cool, wet Tuesday. The weather didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of the overflow crowd of 6,000 on hand to watch the Tigers launch its third season in the Western League. Fans left happy, as following the usual pregame hoopla – a parade, brass bands, some speechifying and a cannon shot – the Tigers clobbered the visitors from Columbus, Ohio, by a score of 17-2.

Along with the outcome of the game, the issue of what to call the Tigers’ new home had been resolved. Owners normally didn’t concern themselves, principally because the wooden parks of the era never were intended to be permanent structures. And nobody in 1896 dreamed of selling the park’s name. Who in the world would want to buy it? And what would they do with it? So it was left to the public to informally decide such matters.

For weeks, local fans had mulled what to call the park. Suggestions had been mailed to owner George Vanderbeck and discussed in the newspapers. They ranged from the prosaic (Vanderbeck Park, League Park) to the more fanciful (American Beauty Park, Au Fait Park).

Soon Detroiters settled on a name. In conversations and in print, the Tigers’ lair habitually was referred to as “Charlie Bennett’s park” -or Bennett Park – as it officially came to be known during its 16 summers of service. There was a purity to the process. There were no polls, no contests, no discussions of merchandising possibilities or corporate tie-ins. It was simply a heartfelt, grassroots form of public applause for a favorite son who had long had trouble putting his own hands together without wincing.

The ballpark sat 5,000 when opened on April 13, 1896 and hosted a spring training exhibition where Detroit walloped Columbus 17-2 and the new field would be named Bennett Park in honor of Detroit's favorite "son", Charlie Bennett.

Bennett Park had been hastily constructed and the stands were rickety. The park featured a peaked roof in the outfield with Home Plate located closer to the corner of Michigan and Trumbull. This area would later be the Right Field of Tiger Stadium.

Bennett Park was home to the first nighttime baseball game in Detroit. On September 24, 1896, the Detroit Creams played their last game of their first season at the Park in an exhibition doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds. Team owner George Arthur Vanderbeck had workers string lights above the stadium for the nighttime game. Nighttime baseball wouldn't return to Detroit until June 15, 1948, when the first game under the lights at Briggs Stadium would be played.

Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson (January 5, 1865 – March 28, 1931), was an American executive in professional baseball who served as the founder and first president of the American League (AL).

Johnson developed the AL—a descendant of the minor league Western League—into a "clean" alternative to the National League, which had become notorious for its rough-and-tumble atmosphere. To encourage a more orderly environment, Johnson strongly supported the new league's umpires, which eventually included Hall of Famer Billy Evans.

Ban Johnson intended to turn his Western League into a major league that would rival the well-established National League. In 1899, he effectively shifted franchises to larger and larger locations. By 1900, he changed the name from the Western League to the American League and within a few years, many baseball fans assumed his league was the equal of the National League. Ban Johnson was a very dominating league president who also was known to tell team owners what they must do to run their teams.

With the help of league owners and managers such as Charles Comiskey, Charles Somers and Jimmy McAleer, Johnson lured top talent to the AL, which soon rivaled the more established National League. Johnson dominated the AL until the mid-1920s, when a public dispute with Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis culminated in his forced resignation as league president.

1901-1902 Detroit Tigers Logo

1901-1902 Detroit Tigers Logo

In March of 1900, George Vanderbeck had decided that he wanted to pursue other interests and decided he would sell his team that he'd built from scratch just a few years earlier. He sold the team for $12,000 to Wayne County Sheriff, James Burns, who owned the team for it's first year in existence.

In 1901, the Detroit baseball club became a charter member of the American League and formalized the name that the team would be known by from that point on. The name would be chosen to honor a famous local military unit that had fought in the Civil War as well as the Spanish-American War. This unit's nickname was "The Tigers" and the team would be known by this name from that day on.

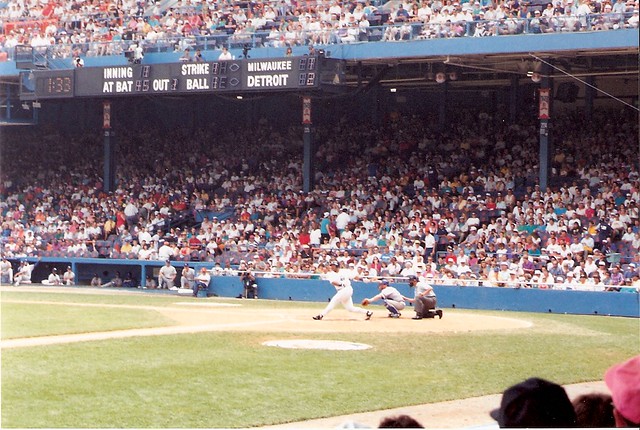

On April 24, 1901, the team prepared to take the field for their first official American League game against Milwaukee in front of a standing-room-only crowd. The unpredictable weather that day unfortunately postponed Opening Day until the following afternoon.

Tigers prepared to take to the field at Bennett Park for their first official American

League game, but unpredictable weather postponed the opening by a day.

Vanderbeck stayed with the organization after he sold the team and would later leave Detroit in 1902. It's not known whether he pursued any further baseball interests afterwards, but he deserves acknowledgements and accolades for the role he played in making sure the Detroit Tigers are represented in major professional baseball.

Sheriff Burns would only own the team for a year and would sell the Tigers in 1902 to Samuel Angus. Angus, would soon sell the Detroit Tigers in 1904 to William Yawkey who inherited a fortune from his father, William C. Yawkey who had been a highly successful Michigan lumber baron and mining entrepreneur in the 1800's.

1904-1907 Tigers "D" Logo

1904-1907 Tigers "D" Logo

William Yawkey's step-son, Tom Yawkey, would own the Boston Red Sox for decades, so baseball would be in the Yawkey family for many years. Frank Navin had worked in the Tiger’s front office for several years at the beginning of the team's history and, under William Yawkey’s ownership, began to run the team. It's said that William Yawkey was something of a prosperous dilettante who did not bother himself with the fiscal details of running a baseball team as Frank Navin not only ran the team but, by 1907 had purchased controlling interest and Yawkey continued hold some shares until his death in 1920.

Ty Cobb steals home for the Detroit Tigers against the Boston Red Sox in 1907

Ty Cobb steals home for the Detroit Tigers against the Boston Red Sox in 1907

Bennett Park enjoyed some big success, even though it was a smaller ballpark. The Tigers and their young sensation Ty Cobb won three consecutive pennants during 1907-1909, but unfortunately, their success ran out in the post-season on each occasion, losing to stronger National League teams in the World Series. This ballpark here at Michigan and Trumbull is actually hallowed ground to fans of the Chicago Cubs, as it was on this site in both 1907 and 1908 that the Cubs clinched their only World Series championships.

Hughie Jennings was the manager of the Tigers for their

3-years-consecutive visits to the playoffs in 1907, 1908, and 1909

The first World Series played at "The Corner" was in 1907, which proved that the Tigers franchise was a contender in the Major Leagues and that the popularity of the team would not diminish anytime soon.

October 11, 1909 World Series

October 11, 1909 World Series

By the 1908 season, the playing field was reduced as the main grandstand was extended into the field by 40 feet. A new bleacher section along the third base side was added increasing the capacity to 10,000.

In 1908 and 1909, there were two more appearances in the Fall Classic making a total of three years running from 1907, 1908, and 1909 making it into the playoffs.

Monday, October 11, 1909: Game 3 of the World Series with Detroit and Pittsburgh.

Interesting to note the spectators on the utility poles behind the stands.

No word on fan injuries from electrocution.

In 1909, there were two new steel-and-concrete stadiums erected in both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for the teams in each of the cities. After a visit to Pittsburgh as part of the World Series, team owner Frank Navin decided that he wanted to build a permanent and safer home for his baseball club and would be 'modern' for the time with many modern amenities and enough space to enjoy the American Pastime.

Pittsburgh's and Philadelphia's stadiums were noted to be "intimate" venues to watch baseball in and were said that due to their size, they would help players have higher-scoring games by allowing many home-runs from players that could achieve such feats. Many of the sports-reporters of the time called them "bandboxes" or "cigar boxes" because of their rectangular dimensions.

Upgrading the Detroit stadium would also allow it to 'compete' with the other stadiums of the time for the small-yet-growing fanbase of baseball fans that were attending the games every day during the season.

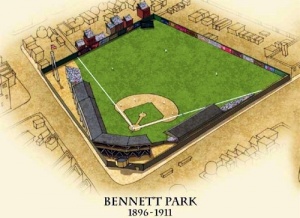

Bennett Park, 1909

Bennett Park, 1909

Bennett Park’s capacity again increased in 1911 to 18,000 when temporary bleachers were added in right and left field. That did not count the "wildcat" bleachers that were built on the rooftops of houses behind the left field fence much like they'd been built many years before at the original Creams stadium. Because Bennett Park was built of wood, one of the biggest threats to the structure was the threat of fire. The decision was made to begin construction on a brand-new steel-and-concrete facility in order to accomodate at least 23,000 fans inside, especially with the growing numbers of baseball fans that seemed to be filling the stadium at every game.

The stadium was haphazardly marked-off with rope in order to separate the fans from the players on the playfield and this solution was not one that either the owners or the players liked. Something new....would soon be on the way to make it a better place to play.

Preparing the field for play

Preparing the field for play

Between the 1911 and 1912 seasons, the Tigers acquired the rest of the block and proceeded to demolished both the wildcat bleachers as well as Bennett Park, and built Navin Field on the same site.

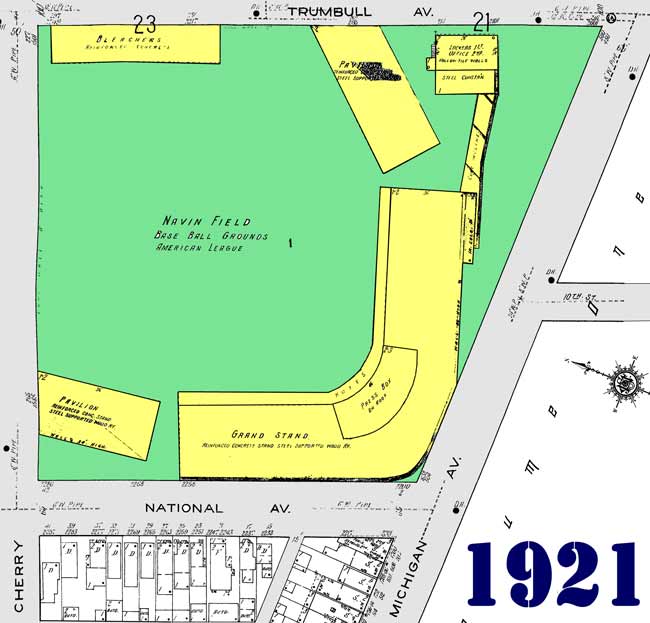

After the 1911 season, Navin had Bennett Park torn down and replaced with the park that you see. Work had to be done hastily, and by March of 1912, laborers worked around the clock. On April 20, 1912, the new park opened with a seating capacity of 23,000 but was designed with a second deck. Interestingly, this is the very same day that Fenway Park opened in Boston. This original component of the park, including the lower deck stands, extending from home plate down the first and third base lines remained throughout its existance as a ballpark. The new park covered about twice the geographic space of Bennett Park.

The Architects for the new ballpark was Osborn Engineering, which was a firm based in Cleveland, Ohio and specialized in building ballparks. They had designed Fenway Park in Boston and League Park in Cleveland. The electrical work was completed by contractor John D. Templeton of Detroit.

A Postcard from Navin Field (listed as Navin Park)

A Postcard from Navin Field (listed as Navin Park)

The biggest change was the new stadium being shifted by 90 degrees, with home plate now where the left field corner had formerly been. This was to allow for the bright afternoon sun that would blind most hitters while they were playing to be able to actually see the ball. The only players that would be affected by the bright sunshine would be the outfielders and the game would be better-played because of this change.

The cost to build the "modern showpiece" was roughly $300,000 and was the pride-and-joy of Frank Navin when it was completed. And so, the new ballpark with the modern (for 1912) conveniences as well as the safety and comfort of the fans in mind, was shown-off as a jewel in the City of Detroit.

The new ballpark would also have a new name. And so it was christened: Navin Field.

Frank Navin (April 18, 1871 – November 13, 1935)

Frank Navin (April 18, 1871 – November 13, 1935)

April 18, 1912, was originally planned to have been a double-grand-slam day for Tigers owner Frank Navin. Not only was it his 41st birthday, but his new ballpark was set to be dedicated with considerable hoopla before a contest with the Cleveland Indians.

Unfortunately, the weather did not cooperate and heavy rains washed out the scheduled affair. Although the game could have been played the following day (a Friday), Navin canceled it. The official explanation was wet grounds. The truth was that the Tigers’ boss, like most gamblers, was extremely superstitious. The man who always put his left shoe on first and avoided cross-eyed people at all costs simply refused to christen Navin Field on what he considered the bad-luck day of the week. The grand opening was rescheduled for Saturday, April 20, the same day Fenway Park would be unveiled in Boston.

Navin Field, circa 1912

Navin Field, circa 1912

On Friday evening, April 19, the Detroit Board of Commerce hosted a banquet saluting Navin and co-owner Bill Yawkey for their commitment to baseball and to the city. The dinner demonstrated how far the Detroit Baseball & Amusement Company (the corporation’s official name) had come in just a few years. The club, once rumored to be moving to Pittsburgh or other places, had stabilized and become a part of the community even to the point of becoming a community resource. This resource's fortunes intertwined with the growing city that it represented on the "square diamond".

Saturday April 20th, 1912 arrived as a cool and hazy day. Many of the dignitaries and VIP's that had attended the previous-night's dinner traveled out to the ballpark in carriages and other "dignified vehicles". Following these fine folks was the members of both ball clubs, a marching band, and a small army of fans. Official totals showed that 24,382 men, women, and children passed through the turnstiles of Navin Field, but estimates of the afternoon’s attendance quickly reached 26,000. Most sat in the yellow-painted wooden slat seats whereas others stood in the roped-off outfield.

Navin Field was a sight to behold. It covered an area nearly twice the size of Bennett Park. With no circus bleachers or other obstacles to clutter the outfield, there was a symmetry to the field and more space to play in. The outfield dimensions were 365 feet down the right-field line, 400 feet to center, and 340 feet down the left-field line. The walls were painted gray and a giant American flag flew from the 125-foot-high flagpole in center field. For many years, it would remain the tallest obstacle ever built in fair territory inside a major-league baseball park.

Inside Navin Field

Inside Navin Field

Fans pointed to the giant scoreboard in left field where out-of-town scores could be easily read from any point inside the park. Players praised the large green panel in center, an innovation that provided a helpful backdrop for batters. Hitters also appreciated the reconfiguration of the diamond. At Bennett Park, home plate had been located at what was now the right-field corner, so that by the end of the game the setting late-afternoon sun was shining directly into the batter’s eyes. Now the right fielder had to contend with that particular problem which was much less of an impact on the game itself on those hard-to-see sunny days in Detroit.

Some fans joked about the long walk to get to their seats and yet others reminisced about Bennett Park’s chumminess and "cozier feel" to it. Overall, Frank Navin’s new park was declared a smashing success by the club, the fans, and even the media. A Detroit News headline expressed the prevailing opinion:

“Fan Verdict: SOME Park.”

1921 diagrams for Navin Field

1921 diagrams for Navin Field

It was also "some game" as well. Cleveland’s “Shoeless Joe” Jackson scored the first run at Navin Field in the opening frame, but in the bottom of the inning Cobb countered with his signature play, stealing home on Vean Gregg’s high pitch to Del Gainor. Catcher Ted Easterly futilely tried to tag Cobb, who executed his famous fadeaway slide. Cobb’s steal of home was his first of eight that season, still the all-time record. Curiously, all occurred at Navin Field, where fans had grown to anticipate such daredevil antics.

Dependable old George Mullin started his ninth home opener in ten years. He went all the way, scattering a dozen hits and pitching out of several jams as the Tigers, down 5-3, rallied to tie the game with a pair of runs in the eighth. In the bottom of the eleventh inning, with two runners on base, Mullin rapped a two-out single between the shortstop and third baseman. That scored Donie Bush and sent Detroiters home happy with a 6-5 victory. The win pushed Detroit to a 4-3 record for the season; they would finish sixth and, thanks to their first losing season since 1906, actually draw 82,000 less fans than they had in their final summer at Bennett Park.

It’s perhaps worth noting that there was no communal outpouring of nostalgia over the passing of Bennett Park, just excitement over the future. Sporting Life declared that the city and its ball team had “just celebrated the most momentous occasion in the history of Michigan baseball. The opening of the new Navin Park can be described in no other way. For the first time in history, Detroit has a ballyard worthy of its rank among the cities.”

Frank Navin (L) and Ty Cobb (R) in 1925

Frank Navin (L) and Ty Cobb (R) in 1925

In May 1912, Frank Navin found himself embroiled in the first player strike in American League history. During a game in New York, Ty Cobb jumped into the stands and attacked a handicapped heckler who had been taunting Cobb with racial epithets. When American League President Ban Johnson suspended Cobb indefinitely, the Tigers voted to strike, refusing to play until the suspension was lifted. When Ban Johnson threatened Navin with a $5,000 per game fine if he failed to field a team, Navin told manager Hughie Jennings to find replacement players. As the Tigers were on the road in Philadelphia, Jennings recruited eight replacement "Tigers" from a neighborhood in North Philadelphia. The replacement Tigers lost 24-2 to the Philadelphia Athletics. The regular Tigers returned after a one-game strike.

Political Demonstration against a school amendment

attended by 100,000 people at Navin Field, 1920

Political Demonstration against a school amendment

attended by 100,000 people at Navin Field, 1920

In 1919, after owner William Yawkey's death, Navin bought 15 shares from the Yawkey estate to become half-owner of the Tigers. He then brokered the sale of 25 percent of the Yawkey interest to auto-body manufacturer Walter Briggs, Sr., and another 25 percent to wheelmaker John Kelsey. After Kelsey's death, Briggs bought Kelsey's interest and became a full partner with Navin, though he stayed in the background.

As far as the stadium itself goes, expansion of the physical stadium would soon commence in order to allow more patrons to the stadium to watch their favorite team battle it out on the diamond.

1930's view of Navin Field/Briggs Stadium

The first major addition to Navin Field occurred before the 1923 season when a second deck was added between the first and third base and a press box was added on top of the roof. This addition increased the capacity at Navin Field to 30,000.

April 20, 1927: The first radio broadcast of a Tigers game.

April 20, 1927: The first radio broadcast of a Tigers game.

Ty Tyson, a fixture behind the mic for 25 years,

calls the game on radio station WWJ

In 1931, Navin was nearly ruined by the Great Depression and by his losses betting on horse racing. Navin had a lifelong love of gambling on horse races, but did not have much luck with winning. He was thus forced to rely more and more on Briggs' money to keep the Tigers competitive since the Tigers' was Navin's only source of income.

Left field as the backdrop for a 1930 Buick Advertisement

Left field as the backdrop for a 1930 Buick Advertisement

By 1933, the Great Depression (and a losing team) had cut attendance at Navin Field to a third of what it had been a decade earlier. Navin contemplated selling the franchise and even entertained an offer from Ty Cobb. But Navin decided not to sell and tried to sign Babe Ruth, hoping to revive interest in the team. Instead, he ended up buying Mickey Cochrane from Connie Mack, who managed the Philadelphia Athletics, for $100,000. Cochrane proved to the spark that helped the Tigers win two consecutive pennants in 1934 and 1935.

Detroit's Navin Field at the corner of Michigan & Trumbull, circa 1934.

For the 1934 World Series at Navin Field, an extra set of bleachers were temporarily built out in left field to accommodate more fans. The stands were built on top of Cherry Street, which gave folks the idea that expansion of the stadium could be feasible.

A view of the field at Navin Stadium in Detroit in 1934.

Because of the ever-increasing amount of fans that came to see the games, the fans were getting packed-in "like sardines" and there was increasingly less-room to move around comfortably.

1934 World Series (looking north towards left-center field with the 'temporary' bleachers center of photo)

1934 World Series (looking north towards left-center field with the 'temporary' bleachers center of photo)

After the Tigers lost the 1934 World Series to the "Gashouse Gang" of the Cardinals from St. Louis, the 64-year-old Navin was reportedly heartbroken, having seen his teams win four American League pennants, only to lose four World Series.

Another view of the left field Bleachers - 1934

Another view of the left field Bleachers - 1934

The 1935 World Series

The 1935 World Series had another championship matchup between the Tigers and the Chicago Cubs. The two teams had met-up in 1907, 1908, 1909, and then in 1934. The 1935 World Series would see the Tigers win their first championship in five appearances in the World Series.

Hank Greenberg (1937)

Hank Greenberg (1937)

The Tigers won despite losing the services of first baseman Hank Greenberg. In Game 2, Greenberg collided with Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett and broke his wrist, sidelining him for the rest of the Series. Marv Owen replaced him at first base and went 1 for 20. Utility infielder Flea Clifton was forced to fill in for Owen at third base and went 0-for-16 in the Series. They had indeed beaten the Cubs.

10-year old William Clay Ford gets a gift from Tigers' manager Mickey Cochrane

10-year old William Clay Ford gets a gift from Tigers' manager Mickey Cochrane

at Navin Field in 1935. His grandfather Henry Ford and father Edsel Ford are to his right.

William Clay Ford would later own the Detroit Lions from 1961 until his passing in 2014.

Six weeks after the championship, on November 13, 1935, Frank Navin passed-away from a heart-attack and fall from his steed that he suffered while riding one of his horses at the Detroit Riding and Hunt Club. hen he suffered a heart attack and fell from the horse. Navin was then buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Southfield, Michigan where the family mausoleum was decorated by Corrado Parducci and is guarded by two tigers by American animalier Frederick Roth.

Walter O. Briggs in his office, 1935

Walter O. Briggs, industrialist and silent partner, then purchases and assumes the responsibilities of the team, the stadium and it's facilities following Navin's passing. Briggs decided that the stadium needed some renovations (again) in order to accomodate the ever-growing amount of fans that were packing in the stadium. Once Briggs was in-control of the team, the stadium underwent a complete makeover and was also renamed Briggs Stadium in honor of the owner, Walter Briggs.

1936 season photo

1936 season photo

Prior to the 1936 season, the single deck pavilion that extended down the first base line and around into right field was double decked. Before the addition could be built in right field, a problem had to be solved. Trumbull Avenue was located behind the right field fence therefore the grandstands could not be expanded out. To solve the problem, the right field line was shortened to 325 feet and the upper deck extended over the lower deck and over the playing field 10 feet.

The 1930's construction of the permanent expansion of the then-renamed Briggs Stadium.

Construction was completed by April 1937 and Briggs Stadium could seat 36,000 fans. After the 1937 season an additional expansion was completed at Briggs Stadium. The City of Detroit agreed to remove Cherry Street, which ran along the back wall of left field. The single deck pavilion that extended down the third base line and around into left field was double decked.

Construction inside the stadium.

A gap between the double decks in right and left field was filled with two decks of bleachers with the scoreboard placed on top. With this expansion, Briggs Stadium was now enclosed and had a capacity of 54,500, making it one of baseballs largest stadiums. Dimensions were 340 ft. (left), 440 ft. (center), and 325 ft. (right).

Briggs Stadium: Mid 1930's

Briggs Stadium: Mid 1930's

The grounds crew marking the lines for a Lions game at Briggs Stadium, 1938.

The grounds crew marking the lines for a Lions game at Briggs Stadium, 1938.

The Detroit Lions of the National Football League began hosting their home games at Briggs Stadium that same year, thanks to an agreement between the Lions and the owner of the stadium. This agreement then kept the facility busy and being used at least 8 months out of the year. The Lions "missed" one year after moving to Briggs, and they went back to their former home at University of Detroit Stadium. This return to U of D would only be for the 1940 season and they would come back "permanently" to Briggs for the 1941 season.

The crowds loved the expansion of Briggs with the also-ever-expanding attendance records that attended games of football, baseball, and other events at the stadium.

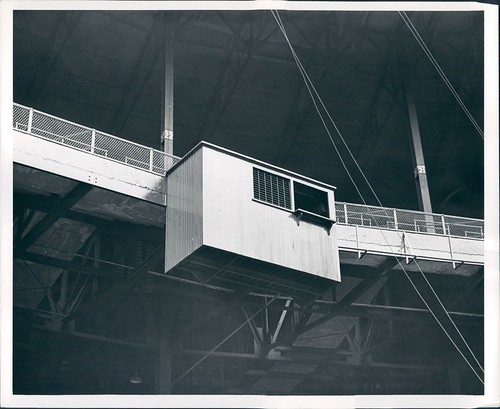

Third deck press box - 1940s

Third deck press box - 1940s

The 1945 World Series

The 1945 World Series matched the American League Detroit Tigers against the National League Chicago Cubs again. The Tigers won the Series, four games to three, giving them their second championship in team history and the first since 1935.

Paul Richards, catcher

Paul Richards, catcher

Paul Richards picked up four runs batted in in the seventh game of the series, to lead the Tigers to the 9–3 game win, and 4–3 Series win

Lighting Up The Game

The first night game at Briggs Stadium (June 15, 1948)

The first night game at Briggs Stadium (June 15, 1948)

Owner Walter Briggs was a traditionalist when it came to baseball. He believed that baseball shouldn't be played at night and refused to add any lighting to his stadium for many years, despite the pressure from the public to do so.

Briggs Stadium, 1948

Briggs Stadium, 1948

Prior to 1948, there had been no games after-dark at Briggs Stadium...but pressure was mounting from the public to make one more addition in the form of night-time illumination for the fans to see their favorite team play.

In 1948, Briggs finally relented to the pressure from the fans and added eight light towers to the stadium to accomodate baseball games to be played at night and Briggs Stadium became the last ballpark in the American League to add night games.

The Stadium, marked-out for the Lions to play.

Apparently, Detroiters liked being night-owl fans as a crowd of 54,480 showed up that evening to see the Bengals trounce Philadelphia, 4-1. This had not been the first time a night game had been played at The Corner, but it was the first one to be played after-dark in over 50 years.

George Kell (Aug 23 1922 - Mar 24, 2009)

George Kell (Aug 23 1922 - Mar 24, 2009)

during his playing days with the Tigers

Also along with the lighting being added in 1948, the Tiger roster that year included Dizzy Trout, Virgil Trucks, Eddie Mayo, and third baseman George Kell. In 1957, Kell would go on to launch a long career in broadcasting both on radio and television.

Ernie Harwell, right, joined George Kell in the Detroit Tigers' broadcast booth in 1960.

George Kell was known for calling the games in his signature Arkansas 'drawl' which endeared him to the fans as a person who loved the game and was intimately involved in it.

Al Kaline (L) and George Kell (R) at Tiger Stadium broadcasting for WDIV-TV4

Al Kaline played in more games at The Corner for the Detroit Tigers

Al Kaline (L) and George Kell (R) at Tiger Stadium broadcasting for WDIV-TV4

Al Kaline played in more games at The Corner for the Detroit Tigers

than any other ballplayer.

Tuesday, June 27th, 1961: Tigers set a then attendance record for a home

Tuesday, June 27th, 1961: Tigers set a then attendance record for a home

night game with 57,271 fans to watch a twi-nighter against the Chisox.

John Earl Fetzer (1901-1991)

John E. Fetzer, who was a radio and TV executive, purchased the Tigers in 1961 and also changed the name of the stadium to it's final name: Tiger Stadium. Fetzer would own the team through the 1983 season and the name of the stadium would remain what Fetzer had changed it to, through the remainder of it's existence here at The Corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

Ushers salute the new season in April 1961 at Tiger Stadium —

which had been Briggs Stadium until it was renamed on Jan. 1, 1961

The stadium would play host to other sports and other teams within its walls over the years. Not only was baseball played at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, as well as the National Football League Lions, but another type of football game were played there too for a very short time in Tiger Stadium history.

Northern Irish semi-professional soccer club Glentoran called the stadium home for two months in 1967. The Glens, as the team from Belfast are known, played under the name Detroit Cougars and was amongst several European teams invited to the States during their off/close season to play in the United Soccer Association.

The soccer club was founded in 1882 and normally plays its home games at the Oval in east Belfast. Club colours are green, red, and black. Because of the use as a Soccer field when the Cougars played here, there were hopes prior to the demolition that Tiger Stadium could have been used and converted into a soccer arena, allowing for a potential MLS franchise, but lack of support by the entities in charge effectively put this idea to rest, permanently.

The 1968 World Series

The 1968 World Series was the Detroit Tigers first appearance in the Fall classic since 1945 and was an amazing feat by the team who came-back from a 3 games to 1 defecit to take the Series Title from the defending Champs, the St. Louis Cardinals.

The '68 series was the third in the teams' history and the last three games of the series were won largely because of the arm of MVP pitcher, Mickey Lolich. He pitched the entire three last games of the series to win it for the Tigers and take the title for the 1968 Season. Lolitch had only had two-days rest when he accomplished this feat in game 7.

The 1968 season was tagged "The Year of the Pitcher", and the Series featured dominant performances from Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson, who was the MVP of both the 1964 World Series and 1967 World Series. In Game 7, Gibson was defeated by series MVP Mickey Lolich, allowing three runs on four straight hits in the decisive seventh inning, although the key play was a Jim Northrup triple that was seemingly misplayed by center fielder Curt Flood and could have been the third out with no runs scoring.

Game 5 of the 1968 World Series when Willie Horton

Game 5 of the 1968 World Series when Willie Horton

threw out Lou Brock at the plate in what would turn out

to be the turning point in a series in which Detroit was down 3-1.

The Series saw the Cardinals lose a Game 7 for the first time in their history. The Tigers, on the other hand, were only the third team to come back from a three games to one deficit to win a best-of-seven World Series. The first two teams to accomplish this were the 1925 Pirates and the 1958 Yankees. Later, the 1979 Pirates and 1985 Royals would accomplish this feat.

The 1968 Detroit Tigers World Champions Team

After 1968, it would be 16 years before the Tigers would make another World Series appearance in the fall classic.

Football 'Grid' at Briggs Stadium/Navin Field/Tiger Stadium from 1938-1974

Prior to the win in the 1968 World Series with its subsequent celebrations, there had been some excitement generated by the prospects of both sports teams that used Tiger Stadium on a regular basis actually actively searching for other venues to play in.

Animation showing the "evolution" changes / additions

Animation showing the "evolution" changes / additions

from Navin, to Briggs, to Tiger Stadium from 1912-1961

The possible reasons for this search may have stemmed from the 1967 riots that scarred the City of Detroit and it's citizens, giving a 'stigma' of sorts to the Corktown neighborhood that was connected to the social-issues of the time.

**1971 All Star Game**

"The National League's Top Hitters" going into the '71 All-Star Game.

"The National League's Top Hitters" going into the '71 All-Star Game.

The excitement had been partially generated by the City of Pontiac making a proposal to create a location for both teams to play in the suburban Oakland County community, even though it was quite some distance from where the current stadium stood.

1971 game against the Minnesota Twins

The Metropolitan Stadium Committee was created to evaluate the possibilities of new stadiums and relocating the two sports teams. The city of Pontiac, MI. (in suburban Oakland County) along with it's community leaders, made a presentation to the committee regarding the use of a 155-acre site on the eastern end of Pontiac near M-59 and I-75.

Sportscasters Paul Carey & Ernie Harwell in the broadcast booth

Sportscasters Paul Carey & Ernie Harwell in the broadcast booth.

Carey joined Ernie Harwell as a Tigers play-by-play announcer in 1973

and spent 19 seasons calling the games until his retirement in 1991.

The commission had a unanimous vote for the location and later appointed a stadium authority which conducted feasability studies to construct a new stadium in that area. Originally, a dual-stadium complex was planned that included the concept of a "moving roof" for the Detroit Tigers portion. This idea for the Tigers' portion was later mothballed due to the lack of commitment by the baseball organization as well as the expense of everything that was involved in that type of structure.

Wayne, Michigan High School Band at Briggs Stadium - 1963

Wayne, Michigan High School Band at Briggs Stadium - 1963

In 1973, ground was broken for the now-landmark Pontiac Silverdome on that site, with only the football franchise being moved into the facility in 1974. This move relocated the football team a little more than 23 miles from where they'd played for many years, just west of Downtown Detroit.

The Lions on the field at Tiger Stadium (unknown date)

The Lions on the field at Tiger Stadium (unknown date)

The Detroit Lions played in Briggs/Tiger Stadium from 1938 to 1974 when they dropped their final Tiger Stadium game to the Denver Broncos on Thanksgiving Day. The football field ran mostly in the outfield from the right field line to left center field parallel with the third base line. The benches for both the Lions and their opponents were on the outfield side of the field.

About the only "leftover" from that time after the Lions moved out was a "possession" football symbol on the auxiliary scoreboard that could be seen whenever you looked at the scoreboard.

The Silverdome would also be used for other large-venue events as well such as concerts and other attractions. This move also left the Detroit Tigers to be the only sports team to play in Tiger Stadium.

A "blocked view" of the diamond from Right Field (1990's)

Beginning in the 1970's, Tiger Stadium began to get a reputation for it's obstructing views and aging facilites, such as restrooms and concession stands. Even with these negatives, it was beloved and remembered by many patrons and local baseball fans for it's historic feel and charm.

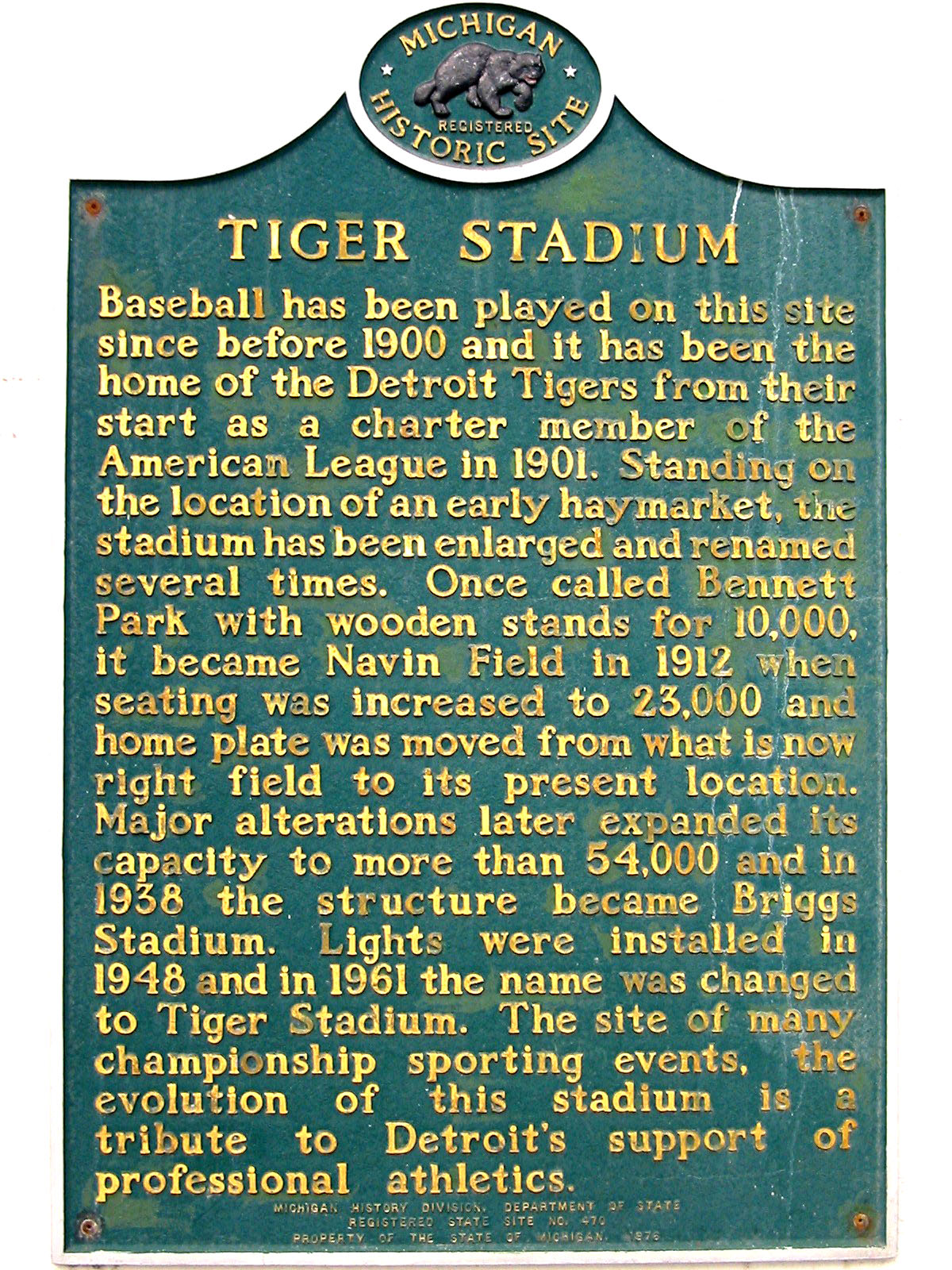

One of the most memorable things about Tiger Stadium was the Michigan Historical Marker that was adorned to the outside of the Building to commemorate it being a treasure of the State of Michigan.

The state historic marker recognizing Tiger Stadium is unveiled by (left to right) Tiger legends

The state historic marker recognizing Tiger Stadium is unveiled by (left to right) Tiger legends

Al Kaline, Hal Newhouser, Billy Rogell, and Charlie Gehringer on August 25, 1976.

February 1, 1977 - Fire at Tiger Stadium

February 1, 1977 - Fire Damaged Tiger Stadium

60 firemen battled a blaze at the aging Tiger Stadium just about 2 hours after it was first reported at 6:33pm EST. It was a three-alarm fire and was confined to the southwest section of the stadium, behind home plate, along the upper deck of the structure. It wiped-out the Press Box, and the immediate dollar-value of the damage was not known when an article was in the newspaper the next day.

Fighting the fire was a challenge because the stadium had not been used since it was wintertime and the entire area was blanketed with snow. Fire fighters had to use hoists to get personnel over the top of the stadium and many of their ladders were stretched to their limits to battle the blaze.

Firefighters battling the flames outside the stadium

Firefighters battling the flames outside the stadium

One of the other challenges was that once firefighters arrived on scene, it took them 10-to-15 minutes to actually enter the stadium because there was limited personnel on-site to gain access to the inside as well as the snow on the ground that hampered efforts to battle the blaze.

Stretching-out the hoses inside of Tiger Stadium to battle the fire - Feb 1977

Stretching-out the hoses inside of Tiger Stadium to battle the fire - Feb 1977

To assist in crowd and spectator-control, police blocked all the streets leading into the area directly surrounding the stadium as this was defnitely a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle and would not soon be forgotten.

The Tigers had recently begun major renovations which had included new field lighting and fixtures, which unfortunately, some were damaged by the smoke and flames.

Firefighters battling the flames (and snow) inside the stadium

Firefighters battling the flames (and snow) inside the stadium

The Detroit Fire Department had the fire contained by 8:21pm and according to one of the Battalion Commanders, the task of fighting the fire would have been much worse had the weather been colder. As it was, the temperatures during the incident were in the mid 20's Farenheit.

Opening day in 1977 still had some things to be repaired, and some of those things were still noticeably damaged from the fire, but baseball once-again came back to the corner of Michigan and Trumbull and the crowds and players enjoyed the stadium once again.

A pair of original Tiger Stadium seats.

A pair of original Tiger Stadium seats.

Later on after the fire-damage was repaired, the Tigers organization would sell the Stadium to the City of Detroit, only to lease it back from the City. The original wooden seats that had been painted green because of the Irish Corktown neighborhood that the Stadium was part of, were removed and replaced with orange and blue heavy-duty plastic ones to match the team's color-scheme.

Replica examples of the replacement seats

Replica examples of the replacement seats

The stadium's interior was also painted blue to match this new color scheme.

1979 Concession Stand

1979 Concession Stand

The fans have always held Tiger Stadium in high esteem, regardless of the views, or the cold, or the "whatevers" that seemed to make it a little less appetizing for some to come down to the ballpark.

One fan even created his own scale-model of the stadium which appeared in the 1980 Tigers Yearbook.

Here's fan Mike Guadiana and his amazing replica of Tiger Stadium from the Detroit Tigers Yearbook.

BELOW is Mike Guadiana recently with his of his model of the Stadium.

Here's fan Mike Guadiana and his amazing replica of Tiger Stadium from the Detroit Tigers Yearbook.

BELOW is Mike Guadiana recently with his of his model of the Stadium.

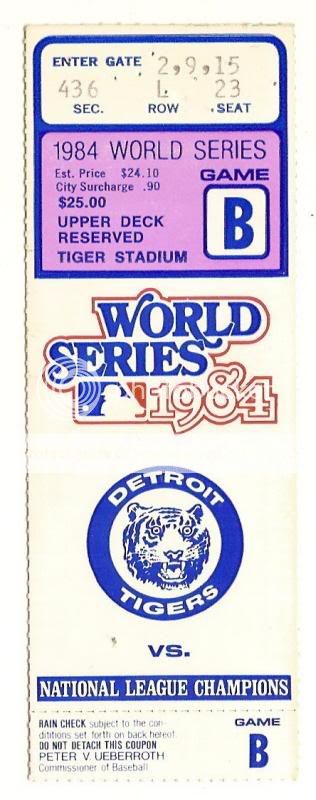

In 1983, Tom Monaghan (the CEO and founder of Domino's Pizza) bought the Detroit Tigers from John Fetzer and continued the tradition of local ownership of the Detroit Tigers by a local businessman. The next year, Monaghan's ownership would see something magical in the organization as the Tigers would go-on to win a World Series Championship in the 'magical' season of 1984.

1984 Season and the World Series

By May 24, 1984, the Detroit Tigers had just won their ninth straight game with pitcher Jack Morris on the mound. The Tigers record stood at 35–5—a major league record. In the next three games they would get swept by the Seattle Mariners and settle down to play .500 ball over the next 40 games.

George "Sparky" Anderson

(February 22, 1934 – November 4, 2010)

who managed the Tigers from June 1979 to October 1995

But in the end, they would wind up with a franchise record 104 wins and become only the third team in MLB history to lead the league wire-to-wire.

Kirk Gibson celebrates his second home run of the final game of the World Series - 10/14/1984

Kirk Gibson celebrates his second home run of the final game of the World Series - 10/14/1984 Alan Trammel after the 1984 World Series Win

Alan Trammel after the 1984 World Series Win

The final score was San Diego Padres – 4, Detroit Tigers – 8.

Ticket from the 1984 World Series

Ticket from the 1984 World Series

Some of the vehicles included some Detroit Police cars, which made the National and International News. These stories unfortunately overshadowed the energy and spirit that the win over the Padres included.

Tigers celebrate the World Series victory Oct 14 1984.

Tigers celebrate the World Series victory Oct 14 1984.

L to R: Doug Bair, Bill Scherrer, Marty Castillo (rear), Darrell Evans (with both arms up),

relief pitcher Willie Hernandez (game closer), and catcher Lance Parrish.

The positive momentum of this would eventually fade and for the most part, it would be a good thing for the City of Detroit, but unfortunately, the 1984 Series would be the last to be played in Tiger Stadium by the beloved Bengals (as they were nicknamed) home team.

The on-field celebration after the Series Win

The on-field celebration after the Series Win

From that time on, the stadium was maintained but no more major improvements were planned or begun to the actual structure itself. There were some external improvements later-on, but that would be a few years off. There was some rumors that began to circulate that made many fans wonder if Tiger Stadium's days would be numbered...and if so, for how long?

In April of 1988, amid speculation that the Tigers were searching for a new stadium to call home, more than a thousand fans circled Tiger Stadium to give it a "stadium hug". The power from that hug would last for the next eleven years until 1999.

Fans "hug" Tiger Stadium in 1988.

Fans "hug" Tiger Stadium in 1988.

With the next ownership change which came in 1992, it was a strange twist of the business-world that the owner of one pizza chain (Dominos Pizza) would sell the Tigers to the owner of another local pizza chain (Little Caesars), Mike Illich. This did change the menu at Tiger Stadium for the fans from Dominos Pizza to Little Caesars Pizza-supplied food, and along with this ownership change came some other changes as well.

Tiger Den cushioned seats

Some of the cosmetic improvements to the ballpark came in the form of the addition of the 'Tiger Den' and Tiger Plaza. The Tiger Den was an area in the lower deck between first and third base that contained padded seats for comfort, and section waiters to serve food and drink. The Tiger Plaza was an area that had concessions and a gift shop and was constructed in the old players parking lot right near the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

Tiger Plaza concessions - 1992

Tiger Plaza concessions - 1992

This made the Stadium a little more fan-friendly and also made it a little more profitable for the vendors at the concession stands as folks were able to get to those stands for their souvenirs and food & drink, instead of being on the inside of the stadium where the long-lines made it seem to be extremely crowded at times.

Tiger Den seats (mid-2000's picture)

Tiger Den seats (mid-2000's picture)

Unfortunately, the 1994 Baseball Season would be cut-short due to a labor dispute in Major League Baseball and end on August 12, 1994. This led to the cancellation of between 931 and 948 games overall throughout the league, including the entire 1994 post-season which also included the 1994 World Series.

This cancellation of the Series was the first since 1904 and gave Major League Baseball the designation of being the first professional sport to lose its entire postseason due to a labor dispute. The strike has been considered one of the worst work stoppages in sports history and it left the fans and the sports world outraged.

The strike would finally end on April 2, 1995 and had little effect on the remainder of the 1995 season.

Upper Deck Bleachers - unknown date

Upper Deck Bleachers - unknown date

After the 1994-95 strike, discussions and plans came together regarding construction of a new ballpark for the Tigers. Many folks thought this was a good idea, as Tiger Stadium was aging ...and not very gracefully. Many repairs and upgrades to the old stadium would need to be done (as well as a large amount of money spent) in order to keep it current and up-to-date for it's fans in the forseeable future.

Even with these ideas, many folks campaigned to save the old stadium, including supporting plans to modify the existing structure and maintain Tiger Stadium as the home of the Tigers as it had been since 1901. This was known as the Cochrane Plan and had many supporters within the community, but not to all those individuals that were part of the Tigers.

A scale model of Tiger Stadium, Post 'Cochrane Plan' remodel

A scale model of Tiger Stadium, Post 'Cochrane Plan' remodel

The Cochrane Plan would have added 73 luxury suites and enlarged the clubhouses and add retail space and a museum. It would have modified/added the 3rd level and would have contained suites and viewing that would have made it feasible to remove 40% of the support posts.

Tiger Cecil Fielder getting ready to hit one off the roof at Tiger Stadium. (Mid-1990's)

Tiger Cecil Fielder getting ready to hit one off the roof at Tiger Stadium. (Mid-1990's)

Unfortunately, for Tiger Stadium, the Cochrane Plan was rumored to have never been seriously considered by the Tigers organization. Ground would soon be broken for the new Comerica Park during the 1997 season, giving the wonderful facility at 2121 Trumbull only a few more years to house America's Favorite Pastime and have fans enjoy the ambiance of a living-antique.

Cecil Fielder at bat in Tiger Stadium

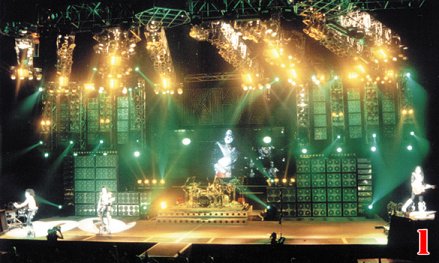

Tiger Stadium had been used for other attractions over the years other than as just a sports-venue. There were a few concerts there including a visit by the hard-rock band KISS, who played at the stadium on June 28, 1996 and made the Tiger Stadium show the first on their reunion tour that year. They played to a crowd of 39,867 fans and the show had the groups Sponge & Stone Temple Pilots as the opening acts.

KISS at Tiger Stadium - June 1996

KISS at Tiger Stadium - June 1996

Tiger Stadium also hosted another concert a few years later, but this time it was not of the hard-driving Rock-n-Roll- type of concert. This one was a bit more elegant and upscale.

The Three Tenors, Plácido Domingo, José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti,

The Three Tenors, Plácido Domingo, José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti,

gave a spectacular performance at Tiger Stadium on July 17, 1999.

On July 19, 1999, the singing trio called The Three Tenors took center field at Tiger Stadium in Detroit for their only North American engagement scheduled for that year.

About 35,000 people attended the concert, wearing everything from silk dresses to khaki shorts, enjoying the evening at the 87-year-old stadium which had been transformed into an opera hall for the evening's event.

Jose Carreras, Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti became the group known as 'The Three Tenors' in 1990 and first performed at the World Cup in Rome, Italy.

A Final Farewell

The program from the final game

The 1999 season began like many had since 1912. The team had not done as well as many had hoped for in the 1999 baseball season and had a team record of 69 wins and 92 losses, finishing 3rd in the American League Central division. The team was Managed by Larry Parrish for their final season at Tiger Stadium, and because of the mediocre record, there wouldn't be any more post-season games, or any Tigers games at The Corner once the move to Comerica Park was made. There had been many fans hopes that the Tigers would do well this season in order to extend the playing-time at the ballpark, but it just wasn't meant-to-be. The swan-song final game for Tiger Stadium having its namesake baseball team play inside the grand old structure would be on that late-September day and it was a grand sendoff to be sure.

The Tigers played their last game at Tiger Stadium on September 27th, 1999.

They beat the Kansas City Royals 8-2.

The game was attended by Detroit City officials, former Tigers personalities, many, many fans, and even construction workers that had been building the Tigers' new home at Comerica Park. This massive amount of people gathered at the old ballpark to give it a grand farewell on that day and make it a memorable one for anyone that was fortunate enough to be there. This solemn September day in 1999 would belong to Tiger Stadium and it's rich sports traditions that had been enjoyed for many, many years here.

The game played-out as most did, with its hits, strikes, and outs, and would end with Todd Jones' final strike-three pitch settling into catcher Brad Ausmus' glove at just-about 7:07pm Eastern Time. The flashbulbs popped, and a roar shook the stadium as none had been heard in a long time....or would ever again at The Corner. The Tigers wrapped-up their stay at Tiger Stadium with an 8-2 win over the Kansas City Royals.

The very last pitch at 7:07pm Sept 27, 1999

The very last pitch at 7:07pm Sept 27, 1999

A banner hung from the upper-deck of the stadium pretty much summed-up the sentiments of many, if not all the baseball fans that attended the sell-out game.

One of the fan-made banners that were in the Stadium that night read:

'Today, there is crying in baseball. Goodbye, old friend'.

Another one of the many banners that hung at Tiger Stadium for the final game.

Normally, season-ending games were melancholy and full of hope for the next season, however, this evening was not a normal evening, by any means. The Post-Game events usually were pretty calm, but the evening of September 27th, 1999 was like none-other before it, or nothing that would ever follow it. This, was the last Detroit Tigers game at Tiger Stadium...ever.

The post-game ceremonies were aimed at recreating many of the treasured memories that had been part of the storied past of the park. Nearly 70 former and current Tigers players and notables took the field for one last time. Fans cheered when each one came trotting out from the dugouts, one-at-a-time. Al Kaline, Kirk Gibson, Willie Horton, Gates Brown, Mark "The Bird" Fidrych, Alan Trammel, and Lou Whitaker, who came out to the sound that hadn't been heard in Motown in many, many years. The fans remembered, and so did Lou. The resounding sound of "LOUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUU" echoed through the stadium one last time. During Whitaker's playing days in Detroit, it was almost commonplace to hear that sound every time "Sweet Lou" would come to bat.

Each of the players was applauded, and cheered, and the memories and emotions poured-out from the many fans that filled Tiger Stadium to capacity just one last time.

From 1912 to 1999, more than 102 million fans passed through Tiger Stadium's turnstiles

The flag bearing the commemorative logo for Tiger Stadium's final year was lowered from the center-field flagpole, then passed down a line of dignitaries including Governor John Engler of Michigan, Major League Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig, all seventy players, and also included relatives of Charlie Bennett who was the 19th Century Detroit Baseball Legend who was the namesake of the original Bennett Field that had been built on this land so many years ago. Relatives of former Team Owners Frank Navin and Walter Briggs were also on hand for this line of dignitaries and it's pretty safe to say, there wasn't too many dry-eyes at the corner that evening.

The final ceremonial pitch was tossed to Brad Ausmus by former Tigers pitcher Elden Auker (who had pitched for the team from 1933 to 1938) to end over 100-years of Professional Baseball at the Corner.

Painted on the dugout during the 1999 season.

The post-game ceremony also included the removal, and later relocation, of Home Plate from Tiger Stadium a short distance away to the new Comerica Park. This process was to include a police motorcade and also included several of the current Tigers team members and also some area Little League players too.

Cecil Fielder waves as the Tigers and Kansas City Royals play

Cecil Fielder waves as the Tigers and Kansas City Royals play

the final game at Tiger Stadium in Detroit on Sept. 27, 1999

Soon after, each of the light standards went dark... as longtime legendary broadcaster Ernie Harwell delivered a moving final farewell to the park, forever etching the memory of this special evening into the hearts and minds of Tigers fans everywhere.

Ernie Harwell at the park

Ernie Harwell at the park

Once the Tigers moved from the ballpark, the use of the facility would change a bit over the next few years. One of the first things that happened was to transform Tiger Stadium into a motion-picture set for a film about (what else?) baseball that was supposed to be set in the early 1960's.

In the summer of 2000, the HBO made-for-tv movie "61*" made Tiger Stadium a movie star. The film was shot in Tiger Stadium after some carefully-done makeover paint and computer animation after-the-fact.

Poster for 61*

Poster for 61*

The film dramatized the efforts of New York Yankees teammates Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris during the 1961 season to break fellow Yankee Babe Ruth's single-season home run record of 60. Roger Maris actually accomplished the feat.

The process of converting Tiger Stadium to Yankee Stadium began with painting seats, columns, walls, stairs, facades and anything that was visible to the distinctive pale light green color of Yankee Stadium before the park underwent a massive renovation in the mid-1970s. In the DVD documentary about the making of the film, production designer Rusty Smith revealed that he believed no accurate representation of the exact shade of green existed until someone in the Yankees organization said that director Billy Crystal, a diehard New York Yankees fan who idolized Mickey Mantle, had a wooden seat from the old stadium. While it was mostly painted blue, there was a large chip that revealed the green paint underneath.

Anthony Michael Hall and two extras from 61*

Anthony Michael Hall and two extras from 61*

However, old Yankee Stadium had three tiers whereas Tiger Stadium had only two. In post-production, the uppermost tier was cloned and pasted on top. Filligrees and other distinctive elements of old Yankee Stadium as well as vistas of The Bronx beyond the walls of the park were also added via CG. Signage completed the illusion. In the ending credits, Tiger Stadium is credited as playing Yankee Stadium. Rusty Smith recounted that when Billy Crystal saw Tiger Stadium dressed as the Yankee Stadium he remembered from his youth, he became very emotional.

Coincidentally, Roger Maris hit his first home

run of the 1961 season at Tiger Stadium.

Upon completion of filming of the Yankee Stadium scenes, the seats and ballpark were repainted to their Tiger Stadium colors and appearance. In the film 61*, Tiger Stadium is shown painted blue, with blue and orange seats, but that was its appearance after a renovation in the late 1970s. In the year 1961, the stadium and the seats were painted dark green because of the area of Detroit known as "Corktown" and the Irish families that had resided there.

This was not Tiger Stadium's only appearance as a

filming location or as a "star" in a movie.

Layout plans for Tiger Stadium to become the 1961 Yankee Stadium

The stadium was depicted in Tiger Town, a 1983 made-for-television baseball movie starring Roy Scheider, and also Sparky Anderson with a small role, and (as Briggs Stadium) in the 1980 feature film Raging Bull where the stadium was the site of two of Jake LaMotta's championship boxing matches. Tiger Stadium was also seen in the film Hardball starring Keanu Reeves, Renaissance Man with Danny DeVito and in the aforementioned film 61*, where it "played" the part of Yankee Stadium as well as itself.

It was also featured in "One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story", a 1978 made-for-TV film and was shown in many scenes as well as a very short scene in the movie "Hardball" where it "played" something called "Chicago Field". It's last TV role was in an HBO TV-series called "Hung".

In 2000, after filming for the movie 61* was finished, a group called "Michigan & Trumbull, LLC" rented the facility for other separate baseball games, but nothing to do with the Tigers. The games were part of the Collegiate Wood Bat League, a vintage baseball game between players that had retired, and a professional women's-league baseball game.

Detroit Danger logo

The women's game was hosted by the Women's Baseball League, Inc. and was played on August 11, 2001 between the Detroit Danger Women's Baseball Club and the Toronto All-Stars. The Danger beat the All-Stars 3-2 and became the first-ever all-women's baseball game to be played at the Corner during it's entire history.

Prior to the Detroit Danger playing, on July 24, 2001, the day Detroit celebrated its 300th birthday, a Great Lakes Summer Collegiate Game was played at the stadium between the Motor City Marauders and the Lake Erie Monarchs. It was in an effort by a local sports management company that is seeking to bring a minor league franchise to Detroit in the Frontier League.

In July 2002, the Tigers sponsored a fantasy camp with instructors Jason Thompson and Milt Wilcox. For many, this was the final time that Tiger Stadium was opened to the public for a baseball-related purpose.

'The corner' - 2005

'The corner' - 2005

Since it was vacated by the Tigers, The Corner has been used periodically to videotape special segments, such as the appearance of Denny McLain on Fox Sports Net's "Beyond the Glory" and a pregame piece for the 2005 Major League Baseball All-Star Game featuring Ernie Harwell.

Looking at the ticket booth at Tiger Stadium

Looking at the ticket booth at Tiger Stadium

In early 2006, the feature-length documentary Stranded at the Corner was released. Funded by local businessman and ardent stadium supporter Peter Comstock Riley, and directed by Gary Glaser, it earned solid reviews and won three Telly awards and two Emmy awards for the film's writer and co-producer, Richard Bak (a local journalist and the author of two books about the stadium). It was also shown at the inaugural National Baseball Hall of Fame Film Festival, held in Cooperstown, New York, November 2006.

The massive tent setup inside Tiger Stadium for the Bud Bowl 2006

The massive tent setup inside Tiger Stadium for the Bud Bowl 2006

In February 2006, Tiger Stadium's field was used for some of the unofficial Super Bowl XL festifities. There was an advertising event promoting the Anheuser-Busch Bud Bowl. Among performers at the nightclub-style event was Snoop Dogg.

After several years out of the public eye, the Bud Bowl event led the Detroit Free Press to make the interior of the stadium the feature of a photo series on February 1, 2006. These photos showed the stadium's deteriorating condition, which included trees and other vegetation growing in the stands. Anheuser-Busch promoted the advertising event as "Tiger Stadium's Last Call".

Ads on the outside for the Bud Bowl 2006

Ads on the outside for the Bud Bowl 2006

The Detroit Police Department has also used the stadium as a practice sniper range. Clips of this were aired on the show Detroit SWAT that aired in the mid-2000's.

Trying to Save The Stadium

Many longtime fans and supporters of Tiger Stadium were disappointed in the initial closing and plans for demoltion for the stadium. There were many private parties and fundraisers to try to raise money to save the aging ballpark. There were non-profit organizations ere not happy about the initial closing and possible demolition of the Stadium. There were many private parties, non-profit organizations, and even some financiers who had expressed an interest in saving the ballpark after it closed. There were proposals to convert it into mixed-use condos and residential lofts that would overlook the existing playing field.

There was even an ambitions plan that involved recruiting and housing a minor-league baseball team in a reconfigured park that would have the feel of the original Navin Field. This plan even included the original size and layout of Navin and would also have a museum, shops, and some conference space.

The now-missing Historical Marker that was near the Box Office.

The now-missing Historical Marker that was near the Box Office.

2006 arrived and Detroit Mayor Kilpatrick made the announcement that would seal the fate of the aging ballpark. "The Corner" would be demolished by the end of the following year, making any prior plans seem contradictory or speculative.

On December 18, 2006, there was a walk-through hosted for potential bidders to remove assets from the stadium that were considered "memorabilia" such as the seating, signage, or anything else considered valuable such as that. Demolition would commence after these items were removed and would be given to the demolition crews as scrap materials that would be liquidated and sold for their scrap value as compensation for the demolition work, instead of the money coming from the City of Detroit.

All items except the foul poles, the center field flagpole, the auxiliary scoreboards along the first and third base lines, and the neon "TIGER STADIUM" lettering would be available. The decision on demolition was delayed initially in March 2007, and was finally made official in June of that same year.

The Demolition

The first "hole" in the stadium

The first "hole" in the stadium

A group called the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy was formed to try to block the demolition efforts and preserve the stadium as much as possible, blocking many efforts by the city to demolish Tiger Stadium and repurpose the land.

On July 27, 2007, the Detroit City Council approved a plan to demolish the stadium. Some of the parts to the stadium like the blue neon signage that read "TIGER STADIUM" as well as some seats were donated the Detroit Historical Society, and some of it was auctioned.

Money to pay for the demoltion was to come from the scrap-value of the materials from the stadium, not the City of Detroit. That way there was no cost to the city to demolish the historical site.

July 10, 2008...it began.

Plans to keep the dugout-to-dugout portion of the stadium were contingent upon the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy being able to raise money to pay for maintenance and security as well as have a financial plan to provide for a possible sports memorabilia "museum".

During the demolition, a final good-bye

During the demolition, a final good-bye

The money was never raised, and the demolition was partially completed in September of 2008. At that time, a deadline of March 1st, 2009 was set for the conservancy to raise more money for the museum, educational space, and a working ball field.

Left: 2007 view from across the street at Michigan and Trumbull. Right: April 20, 2012

Money was raised, and time was given, but neither one seemed to matter and neither was enough to avert the inevitable end of the grand old ballpark. Money from the government was also allotted by a proposed spending bill by US Senator Carl Levin. None of it, ever seemed to be enough even though Senator Levin's bill made federal money available for "...preservation and redevelopment of a public park and related business activities."

One last filming...

During the very last days where at least part of Tiger Stadium was still standing, what remained was used as scenes for the film, "Kill The Irishman", which depicted the old Cleveland Municipal baseball stadium that had been demolished years before. This filming extended demolition for a single day...but that would be all. Demolition continued the next day after the single-day shoot at Tiger Stadium on June 5, 2009.

The beginning ... of the end

The last remaining part of the structure fell at

approximately 9:24 am, Monday, September 21, 2009.

The scoreboard being trailered to Wayne State

The scoreboard being trailered to Wayne State

Reminders and memorabilia of Tiger Stadium do remain nearby, even if they aren't where they were for many years at The Corner. On Dec. 16, 2009, the left field scoreboard from Tiger Stadium was installed at the baseball field at Wayne State University and continues to be used to this day. Many folks think it’s great that such a recognizable piece of Tiger Stadium has found a meaningful home just down the street from its original home.

The blue neon sign that stood atop the roof at Tiger Stadium.

The blue neon sign that stood atop the roof at Tiger Stadium.

The Detroit Historical Museum has installed the old blue

The Detroit Historical Museum has installed the old blue

and white sign from Tiger Stadium as part the