Nooherooka Tuscarora Traditional Geocache

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (micro)

(micro)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

Having driven by this monument dozens of times in the past few years it has baffled me why there is not a cache hidden here so I decided to rectify that. Finally having had a chance to stop and investigate this very interesting road side feature. I hope if you get a chance to search for this cache that you would consider taking time to read about this totally unexpected gem of history in the middle of rural North Carolina.

Below is a summary of the information about this memorial site.

A powerful band of American Indians built a pine-log fort on this flat land outside Snow Hill, steeling themselves for battle with English colonists and their Indian allies, loading their muskets with powder and balls. There’s nothing left to suggest the cataclysm that followed: 900 Tuscarora men, women and children either burned, shot, scalped or sold into slavery. This Waterloo for the North Carolina natives remains almost wiped from North Carolina’s memory, it happened in March 1713 – 300 years ago.

Largely forgotten, unfamiliar even to people who grew up in eastern North Carolina, the fighting at Nooherooka triggered a change in colonial America that would not only scatter and divide the Tuscarora tribe, but help speed a bloody policy of eradication. The history-book names that followed in the next century – Little Big Horn, Wounded Knee – can be traced back to here.

Nooherooka – sometimes spelled Neoheroka or Neyuheruke and pronounced Noo-her-oo-kuh. A monument is all that remains a few hundred yards from the fort’s remains.

The campus of East Carolina University resides on Tuscarora land. The land this monument stands on was donated by the nearby farmers to ECU for the purpose of building this monument The Eastern Band of Cherokee is probably the best-known tribe in the Tar Heel state, both for its story of forced migration on the “Trail of Tears” and for its casino in the Blue Ridge Mountains. To date, they are the only tribe in the state with a reservation, the Qualla Boundary.

The Lumbee Tribe is the state’s largest with roughly 55,000 members concentrated around Robeson County. But after more than 100 years of trying, the tribe has yet to gain federal recognition. More than 4,000 members of the Haliwa-Saponi tribe live mostly in Warren and Halifax counties along the Virginia border, tracing their roots to the 17th century.

That leaves the Tuscarora.

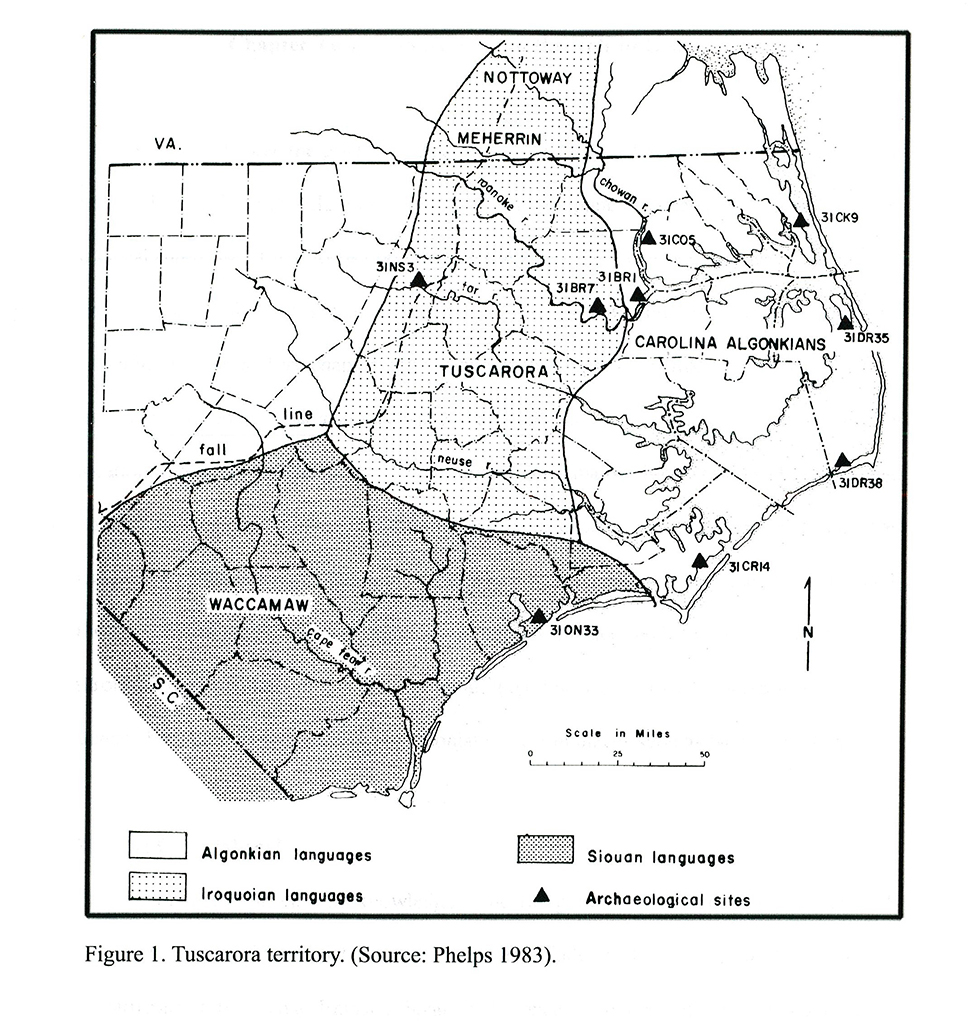

In colonial times, the tribe controlled much of North Carolina east of what is now Interstate 95. They farmed, hunted and fished in the land around the future ECU. They built longhouses throughout the Neuse River basin, much like the Iroquois further north. Before 1729, when it became a royal colony, North Carolina was largely a scattering of small settlements managed by gentleman adventurers. In some cases, colonists arrived having purchased land they had never seen, not knowing the Tuscarora were already living there. Around that time, English explorer and naturalist John Lawson navigated parts of the state unknown to European settlers, founding Bath in 1700 as the state’s first town. By most accounts, he respected and admired the Indians he met, making notes on their culture in his diary, surveying land in hopes of attracting investment. Relations soon worsened. Traders and colonists arrived who did not share Lawson’s open-mindedness. They cheated tribes in the region, forced them off hunting and farming land, shot them and sold them into slavery. Indians felt degraded by whites who plied them with liquor and considered them beasts. Native children were routinely kidnapped and enslaved. Tensions flared further in 1711, when the Tuscarora captured Lawson as he paddled up the Neuse River in search of a new passage to Virginia. After the tribe set Lawson free, a nearby Coree chief ordered him executed. Some say Lawson died by fire; others by having his throat slit. But soon after, the Tuscarora War began as roughly 500 Indians attacked colonists along the Neuse and Pamlico rivers, killing roughly 130 them and taking 20 more prisoner.

Retaliation came when troops marched from South Carolina, bringing a few dozen white men and about 1,000 Indians who were hostile to the Tuscarora, including Yamasee and Cherokee. Meanwhile, the Tuscarora massed inside their fort between what is now Goldsboro and Greenville: Nooherooka.

The Tuscarora were well armed with muskets rather than bows and arrows. But the attackers brought 3-pound cannons and an early form of grenades, lighting the fort walls on fire. Hundreds burned inside. Many more were scalped. Survivors fled, most of them making their way to New York where a reservation now stands near Niagara Falls. ECU History professor Dr. Larry Tise has visited with them and discovered amazingly that they still consider North Carolina home after three centuries in exile. They do not recognize the United States government as anything but a foreign invader, he said. They have no police on the reservation, and no garbage collection. They could have a casino but they don’t want one. When they come to North Carolina, it’s like they’re walking on sacred ground. They touch the trees and say, ‘This is what a loblolly pine feels like.’

In the 300 years since the battle, only three families have farmed the land where it raged. When this land was bought it in 1909, it was called Nehucky Farm – a derivative of the name for the Tuscarora’s last stand. The purchaser’s father plowed the land and routinely turned up beads and lead balls in the soil. The Nooherooka had a game of bowling they played, and the ball they used was a cannonball.

In the 1990s, ECU professors dug on the site, turning up the location of the fort’s wall and skeletal remains of the Indians who fell there. The land purchaser’s father befriended Chief Kenneth Patterson of the New York Tuscarora, who visited the site. The land owner donated this public easement, making space for the monument that stands here and to the Tuscarora this is sacred ground.

After the war with the Tuscarora, North Carolina became a royal colony. Indian tribes no longer appeared on maps of the state. Rather, they became the colony’s official enemies, and under international law of the time, killing enemies of the state was legal and acceptable. Their disappearance from eastern North Carolina has much to do with the obscurity of their history. Even today residents of Tuscarora heritage who call themselves mostly Indian, mixed with other races are accustomed to being identified as black.

Additional Hints

(Decrypt)

.ryvc xpbe rteny rug jbyro qahbet rug bg gkra xpbe yynzf n qavuro fv gV .tavxbby ryvuj garzhabz fvug ab fxpbe tvo rug sb lan ribz gba bQ .fxpbe rug av arqqvu bepvz n ebs tavxbby ren hbl