To claim a find for this earth cache you have to e-mail the following to the cache owner...

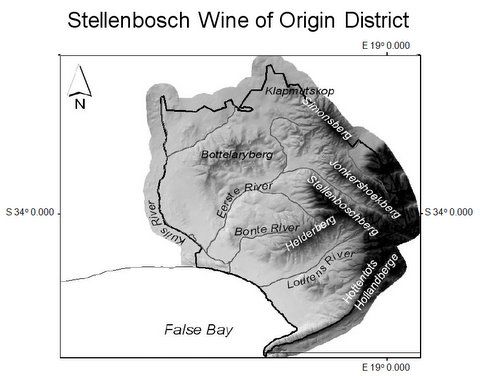

1) A photo or description of any of the geological or topographical terroir components you can see from the published co-ordinates and explain briefly how this could impact on the growing conditions experienced by the vines (refer to the above sketch for help).

2) Do you think the soil at the published co-ordinates is igneous (granitic) or sedimentary (sandstone) in origin? How would this compare to the colluvial soils across the Bonte river valley on the northern slopes of the Helderberg?

3) The largish rocks scattered throughout the vineyard is locally known as “koffieklip”. How did these rocks form (a simple Wiki search will yield the answer) and how do you think would this process impact on the physical properties of the soil? |

THE CONCEPT OF TERROIR

Terroir is a French term with no exact English counterpart and is defined as the sum of all the natural components, especially geology, topography and climate, which may potentially influence grapevine physiology and as a result the character, style and quality of wine. Terroir therefore forms the basis of the appellation system (a legal framework that protects the geographical indication of wine [and other foods], e.g. Champagne vs. sparkling wine and Stellenbosch Wine of Origin), which assumes that the land on which grapes are grown imparts a unique quality that is specific to that region.

The scope, influence and value of terroir are hotly debated subjects, which often come down to the mystical vs. the scientific, old vs. new world views or the “haves” vs. the “have-nots”. Moreover, because it can be used as a powerful marketing tool, the value of having “good terroir” vineyards (at least in name) can have a direct impact on a cellar’s prestige and income. There is no denying that the quality of a wine can be dramatically influenced by the growing conditions of the grapes, but to ascribe this to a rather vague notion of “good” or “bad” terroir, primarily defined by geography, is much too simplistic. So, in an attempt to better define and quantify the impact of this multifaceted entity, viticulturalists and oenologists are trying to define standard, measurable clusters of growing conditions, which can be correlated with specific wine quality parameters. These so called “natural terroir units” are defined as units of the earth’s surface that are characterised by relatively homogenous patterns of geology, topography and climate.

The scope, influence and value of terroir are hotly debated subjects, which often come down to the mystical vs. the scientific, old vs. new world views or the “haves” vs. the “have-nots”. Moreover, because it can be used as a powerful marketing tool, the value of having “good terroir” vineyards (at least in name) can have a direct impact on a cellar’s prestige and income. There is no denying that the quality of a wine can be dramatically influenced by the growing conditions of the grapes, but to ascribe this to a rather vague notion of “good” or “bad” terroir, primarily defined by geography, is much too simplistic. So, in an attempt to better define and quantify the impact of this multifaceted entity, viticulturalists and oenologists are trying to define standard, measurable clusters of growing conditions, which can be correlated with specific wine quality parameters. These so called “natural terroir units” are defined as units of the earth’s surface that are characterised by relatively homogenous patterns of geology, topography and climate.

THE COMPONENTS OF TERROIR

Geology

The geology of a vineyard potentially has both direct and indirect effects on wine character and quality and includes effects of the underlying bedrock, the overlying soil horizon’s physical and chemical characteristics and variations in topography. Generally speaking, the soil has the major influence on vine growth as it provides for the three basic requirements for plant growth, i.e. anchorage, a supply of water and a source of nutrients. Definable aspects of vineyard geology which are of specific importance include soil hydrology (soil moisture relations), pedology (top- and subsoil depth, texture, granulometry [distribution of particle sizes], induration [becoming hardened], mineralogy and chemistry), geomorphology (altitude, slope, aspect) and morphoclimatology (influence of landscape on local climate).

Bedrock: The bedrock is usually solid, unweathered material from which plant roots derive little benefit. The nature of the bedrock can however influence important soil factors such as the nutrient content and pH levels. For example, areas with granite bedrock form acidic soils, which could restrict root growth. Underlying rocks also contribute to the physical properties of soils, affecting in turn the water supply to the vine.

Soil: Soil has a definite effect on the quality of wines under the same climatic conditions but this effect is not consistent over seasons, indicating an inter-relationship between soil and climate. Although soil characteristics such as chemical composition and temperature definitely play a role in the effect of soil on the growth pattern of the vine and, consequently, wine character and quality, the most convincing indications are that the main effect of soil type is through its physical properties (e.g. particle size) and, more specifically, through the regulation of the water supply to the grapevine. For successful viticulture the soil must possess good drainage qualities yet should also be capable of supplying water to the vine throughout the year, including dry periods. Based on elemental analyses, the notion of being able to directly taste vineyard geology (e.g. the mineral elements derived from the soil) in wine (the so called gout de terroir or “taste of earth”) is a romantic notion which is wholly anecdotal and in any literal way is scientifically impossible.

In South Africa three main types of vineyard soils are important. First are the residual and colluvial (transported by gravity down a slope) soils produced as a direct result of the weathering and chemical breakdown of the local bedrock (i.e. soil movement only on a local scale, so there is a direct association between the soil and the geology). Vineyards on the mountain slopes around Stellenbosch (including this cache site which has residual granitic soils), Paarl and Franschoek are examples of this. The second important group are the alluvial soils, which have been deposited by the action of water – predominantly rivers. Alluvial soil characteristics vary widely, ranging from gravel deposits to clay layers. These are important for vineyards in the Berg, Breede and Olifants river valleys. Soils deposited by wind action form the third type of soil. These aeolian soils are sandy, and typically cover a residual clay subsoil layer. They feature in some vineyards in the Bottelary and Koelenhof areas to the north and west of Stellenbosch. In both of the last two cases the soil characteristics are normally unrelated to the immediate bedrock geology, as the soil material has been transported, often for large distances, from its source.

Topography

Topography

The effect of topography on temperature variability (above and below ground) can be considered to be one of the main factors affecting the quality of grapes. Topographic effects on climate can be indirect, due to drainage, exposure to wind, drainage of cold air, or direct, due to its immediate effects on the incidence of the sun’s rays on the earth’s surface.

Slope gradient, shape and aspect: Slope affects temperature and water retention via sunlight interception, exposure to winds and rainfall and soil water drainage. Convex landscape forms will generally result in less day-night temperature variation in comparison to concave forms, while concave slopes often result in accumulation of soil moisture and nutrients at the foot of the slope. Increasing altitude also tends to result in decreasing temperature (1°C decrease per 100 m increase for dry air).

Climate

A variety of mesoclimates (i.e. “local” climates) can be identified in a hilly or mountainous region as a result of topographical effects on various climatic elements (morphoclimatology). Large bodies of water (including oceans), for example, have a modifying effect on temperature due to their temperature inertia, resulting in the reduction of both the diurnal temperature range and the contrast between minimum and maximum temperatures.

Temperature, relative humidity and wind: Temperature is one of the most important climatic parameters affecting grapevine as it has an effect on almost every aspect of the vine’s physiology. High temperatures will, for example, result in grape juice with higher sugar content and lower acid content. Similarly temperature could impact on the pH, flavour, aroma and colour compounds of wine. Low relative humidity reduces growth and yield while high relative humidity values can increase disease incidence. Wind has both positive and negative effects for viticulture. Strong winds in spring and early summer can injure new growth and young bunches, as well as reducing fruit set. Air circulation, however, prevents high relative humidity and excessively high temperatures from developing in vine canopies. In areas where the soil has a potential for high vigour, strong winds may be conducive to quality by limiting the vegetative growth of the vine.

CONCLUSION

Terroir refers to the “all inclusive” growing environment of wine grapes, which have a large influence on the physiology of the plants and subsequently on the character and quality of the wines they yield (visually represented in the sketch below). Geology is one of the main components of terroir and impacts directly on it through the formative effects of geological processes on soil assemblages and composition, landscapes and microclimates.

References

Bargmann JC (2005). Geology and wine in South Africa. Geoscientist 15(4), 4-8.

Bohmrich RC (2006). The Next Chapter in the Terroir Debate. Wine Business Monthly 13(1), 88-93.

Carey VA, Archer E & Saayman D (2002). Natural Terroir Units: What are they? How can they help the wine farmer? Wineland (February) 86-88.

Maltman A (2008). The Role of Vineyard Geology in Wine Typicity. Journal of wine research 19(1), 1-17.

Meinert L (2004). Understanding the Mysteries of the Grape. Geotimes http://www.geotimes.org/aug04/feature_terroir.html#authors.

Acknowledgement: A big thank you to Cincol and Carbon Hunter who helped us develop our first earth cache.

*******************************************

FTF:  and mm1za

and mm1za