This requires a decent hike in from either the Devil’s

Punchbowl County park or South Fork Campground. The examples

listed here are just off the trail along hard rock.

This requires a decent hike in from either the Devil’s

Punchbowl County park or South Fork Campground. The examples

listed here are just off the trail along hard rock.

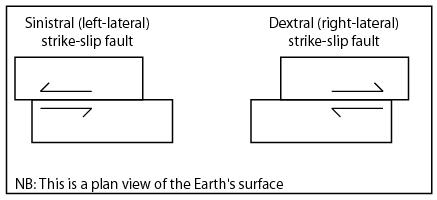

The nearby San Andreas and the abandoned Punchbowl fault are

both strike-slip faults. Movement on strike slip faults is almost

all horizontal with little vertical movement. These kinds of faults

are described as either sinistral (left-lateral) or dextral

(right-lateral) depending upon how the rock blocks move relative to

each other. For sinistral faults, the rock on the other side of the

fault appears to have moved left relative to first block. And for a

dextral fault, the rock on the other side of the fault appears to

have moved right.

What does that actually mean? Imagine you were watching a tree on

the other side of a strike-slip fault during an earthquake. If the

fault was sinistral, at the end of the earthquake, the tree would

appear to have moved further to your left and if it was dextral,

the tree would appear to have moved further to your right. Notice,

it doesn’t matter which side of the fault you are on, the other

side of the fault will always have the same relative movement. The

diagram is from the viewpoint of a balloon above the fault.

What does that actually mean? Imagine you were watching a tree on

the other side of a strike-slip fault during an earthquake. If the

fault was sinistral, at the end of the earthquake, the tree would

appear to have moved further to your left and if it was dextral,

the tree would appear to have moved further to your right. Notice,

it doesn’t matter which side of the fault you are on, the other

side of the fault will always have the same relative movement. The

diagram is from the viewpoint of a balloon above the fault.

This is a rather dry textbook description and description. Now

how do you actually recognize or identify this movement in the

field? The coordinates bring you to an outcrop where you can find

small strike-slip faults of both styles. You are looking for two

8-inche diameter rocks, one red and black and one olive tan. They

are within about 3 feet of each other. If you are having trouble

finding them, they are located beneath my sunglasses and gps in the

attached picture. Each rock has a strike-slip fault that has sliced

the rock into two pieces. One fault is sinistral and the other is

dextral.

Stand on one side of the fault, it doesn’t matter which side.

Imagine the rock as a single piece and then imagine which way the

rock on the other side of the fault would have to move to get to

its current position. This method can be used on any size fault to

determine the style of strike slip faulting, even one as large as a

plate boundary such as the San Andreas Fault.

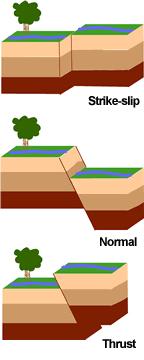

The secondary coordinates take you to another style of faulting,

called either normal or reverse (thrust) faulting. Movement along

this kind of fault is primarily vertical, one side will move up or

down relative to the other. These faults are usually slanted to

some degree so you can picture the fault as a hill. In a normal

fault, the rocks appear to slide down the fault as you would expect

gravity to pull something down the hill. In a reverse or thrust

fault, the rocks appear to have been pushed up the hill.

The secondary coordinates take you to another style of faulting,

called either normal or reverse (thrust) faulting. Movement along

this kind of fault is primarily vertical, one side will move up or

down relative to the other. These faults are usually slanted to

some degree so you can picture the fault as a hill. In a normal

fault, the rocks appear to slide down the fault as you would expect

gravity to pull something down the hill. In a reverse or thrust

fault, the rocks appear to have been pushed up the hill.

Normal faulting is characteristic of rocks being pulled apart.

As the rocks pull away from each other, material falls down to fill

in the space created. Reverse faulting is characteristic of

compression. Rocks being pushed together will pile up on top of

eachother.

Logging requirements:

Send me a note with :

- The text "GC1AH5X Which way the Fault Goes?" on the first

line

- The number of people in your group.

- The color of each rock and the style of strike-slip fault that

cuts it.

- Is the style of faulting at the secondary coordinates normal or

reverse?

The above information was compiled from the

following sources:

- Fault (geology), Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geologic_fault

More detail

Many minor faults are generated adjacent to a primary fault. These

minor faults form to release the stress and strain created by the

primary fault. These minor faults do not have to have the same

style of faulting as the primary fault.