Brown's Folly - cambering and landslips EarthCache

Brown's Folly - cambering and landslips

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (other)

(other)

Related Web Page

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

An investigation of an oolitic limestone, cambering and landslips

Brown’s Folly is a nature reserve and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for its Middle Jurassic rocks. The EarthCache is here with the permission of The Reserves Manager, Avon Wildlife Trust.

This EarthCache is site 11 on the Brown's Folly geological trail. You can reach this on the path which is parallel to the road from the car park. If, however, you are walking from Brown's Folly - Jurassic limestone outcrops GC4DY3P, from Site 10 (the last waypoint), walk back to the gate (do not go through) and go down the path parallel to the fence until you find a path going steeply down through the wooded area, (N 51 23.695 W 002 17.861). Continue down until you reach a made-up track, (N 51 23.740 W 002 17.878). On the way down, the rocks that lie below the Bath Oolite are seen on the right-hand side. Turn right along the made-up ride until you reach this EarthCache, Site 11.

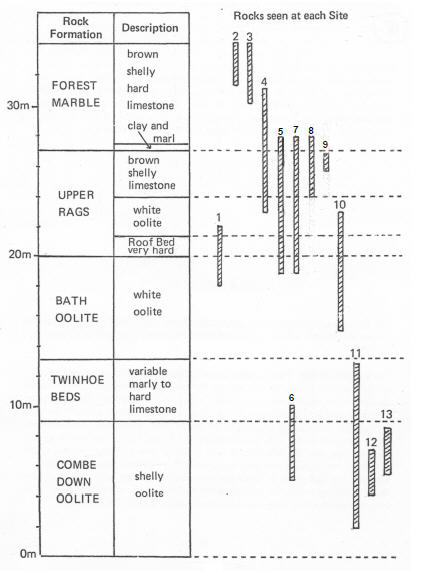

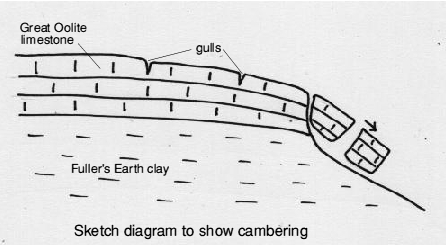

The rocks you are looking at here are the lowest and so the oldest in the sequence. The Combe Down Oolite is at the bottom with the Twinhoe Beds right at the top of the slope. In front of the rock faces here you can see large blocks of rock that have broken off from the main rock mass and slipped or rolled down slope. This is caused by cambering, something which occurs around all the hills of Bath. It occurs in a rigid 'cap' rock (the limestones at Brown's Folly) where there is subsidence in less coherent, more plastic rocks beneath; in this case, the Fuller's Earth clay. Where there is a valley, the Bristol Avon here, this leads to a downslope bending and tilting of the strata and the collapse of the top rocks down the slope causing landslips and slumping of material. This is the cause of most of the landslips around Bath. Of course, the process is assisted by the fact that water tends to go through the limestones, they are both porous and permeable, but it cannot go through the impermeable clay band beneath so the junction becomes slippery and wet. This explains the occurrence of springs at the base of the limestone.

Although no evidence has yet been found at Brown's Folly, cambering widens joints in the rigid cap rock. Gulls, a colloquial name for ‘gulleys’ or chasms, are the result of widening of these joints. The gulls may be large, open cracks but are often infilled with superficial deposits that have collapsed into the voids; sometimes they contain fossils of creatures that roamed the area in the last glacial advance.

The rock faces are reached by a short scramble up the slope but please take care as the slope is steep and the ground is rough under foot. The right-hand face consists of the Combe Down Oolite, the oldest rock in the reserve. If you have investigated the other EarthCaches at Brown's Folly, you will notice that this rock is clearly different from the other oolites seen so far. It is darker in colour and contains a considerable amount of fossil debris and some small whole fossils. The rock is not suitable for working as a freestone here, but south of Bath at Come Down and Odd Down its nature changes and it has been and still is worked for building purposes. It is less porous than the Bath Oolite and therefore withstands the weather better. Cross the scree to the left-hand face. This is again the Combe Down Oolite and the base is deeply undercut forming a cave. It seems probable that the cave was made by the removal of stones for local wall building.

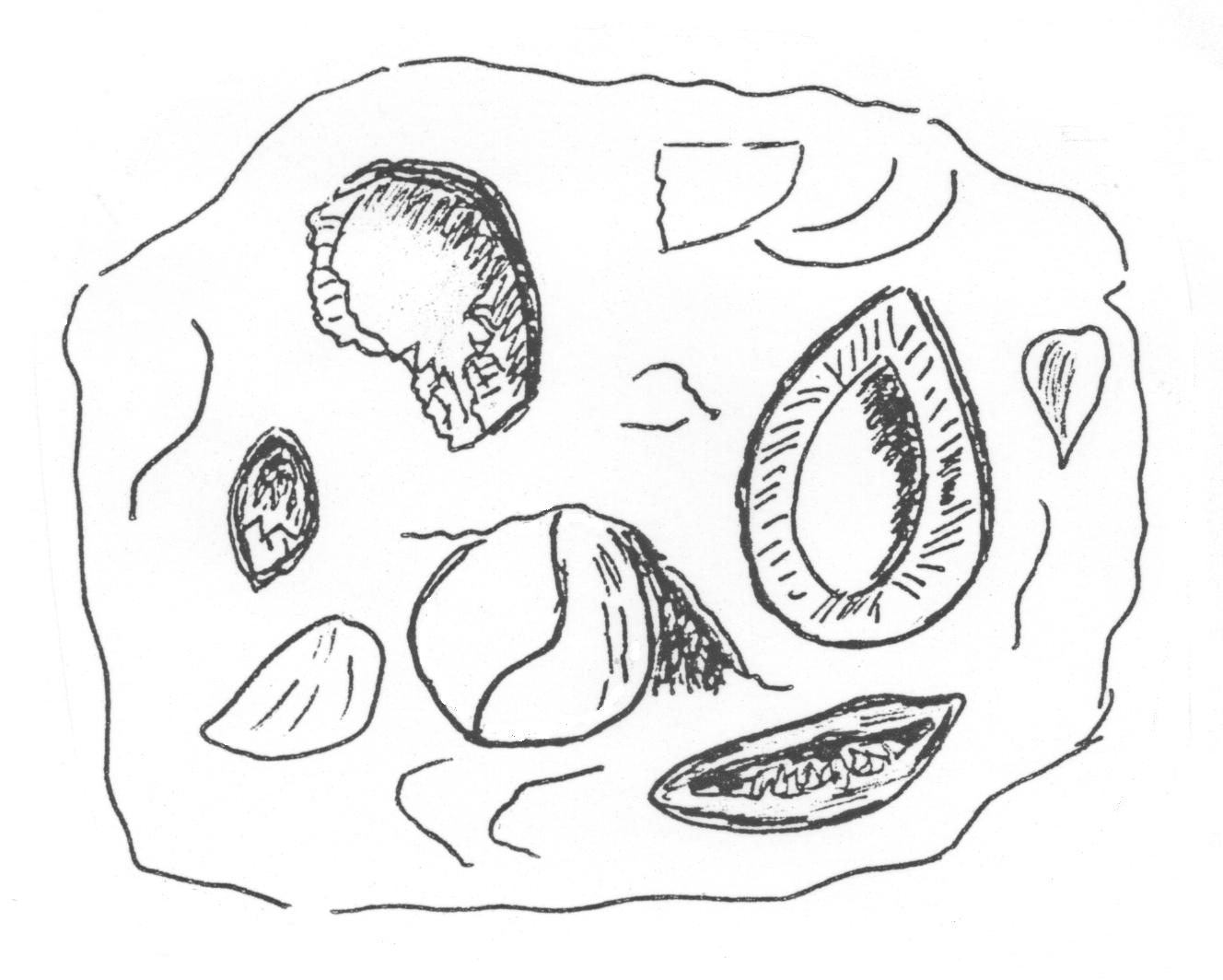

Climb the scree at the right side of this left-hand face and locate a band of rock containing a large number of brachiopods or lamp shells (see diagram below). These are very difficult to find and please do not hammer the face. If you find them, and you can see a section through a brachiopod, the inside of the shell is rimmed with calcite and the rest of the shell is empty.

If you look at a number of pieces of the Combe Down Oolite, you will agree that is is very variable. The variable nature reflects the complex changing environment in which it was formed. By analogy with environments where similar sediments are being deposited today, it is considered that the Combe Down Oolites were formed in shallow water with strong tidal currents. It is unlikely that there were many indigenous organisms or active ooid formation; both of these having been swept into the area from outside. At times, stable conditions would have existed and the brachiopod bed indicates one of these periods when conditions were stable and large numbers of brachiopods became established. The fact that the shells of these are now rimmed inside with calcite and no sediment being inside the shell suggests that they were shut tight when they were buried and they may well have been buried in their life position.

The band of brachiopods is about 1m below the top of the Combe Down Oolite. Above this are the Twinhoe Beds, the name being taken from the village of Twinhoe near which they could once be well-seen in an old quarry. These beds consist of a wide variety of rock types from hard shelly limestones to soft clayey bands, the differing nature of the beds being reflected in the way they have weathered. Some beds are very fossiliferous, containing bivalves, brachiopods and small gastropods. The beds immediately above the Combe Down Oolite are quite distinctive in hand specimen, a fresh surface showing dark brown rims surrounding many of the ooid-like particles. The brown rims are the result of replacement of the outside of the particles by an iron oxide and this type of rock is often called ironshot. A detailed examination of the rock (see diagram below) shows that true ooids are quite rare, the ooid-like particles being composite grains of ooids and small shelly debris bound together by an algal growth, though the exact nature of this cannot be determined because the iron replacement has obliterated all detail.

What to do:

1. look at about three fresh (i.e. not weathered) specimens of the Combe Down Oolite. Describe what you see.

2. Estimate the size and weight of the big block that has fallen down the slope. Length(m) x width(m) x height(m) will give you its volume in cubic metres. If you multiply this answer by 2 you will have worked out the weight of the block. This limestone is about 2 tonnes per cubic metre.

3. Photos would be lovely but they are optional.

As you continue along the path towards the next waypoint, you will see Site 12 of the geological trail on your right. The Combe Down Oolite is again exposed here and shows excellent cross-bedding.

Waypoint 2, N 51 23.755 W 002 17.544 is site 13, the last site of the geological trail on the reserve. The rocks here are the topmost Combe Down Oolite and the features to note are the very well preserved burrows and the complex cross-bedding shown on the left hand side of the face.

What to do:

1. Estimate the size of one of the largest burrows.

2. What do you think created them?

Email your answers to me, JurassicEdie

Additional Hints

(Decrypt)

Nyy fvgrf pna or ernpurq ol choyvp sbbgcnguf