Wooley Creek Batholith Earth Cache Site – Klamath National Forest

A Note of Encouragement

Welcome to the Klamath National Forest Earth Cache program! Most of the Earth Cache locations are located away from established recreational trails and roads. Visitors are strongly encouraged to check with Ranger District offices for information on current road and trail conditions before visiting sites, and be prepared for cross-country hiking.

Layered clothing, water, and appropriate maps are essentials when traversing the remote, rugged landscape of the Klamath National Forest. Please be aware of wildlife and poison oak while visiting Earth Cache locations in the forest and use caution when traveling on narrow winding forest roads.

Location Information

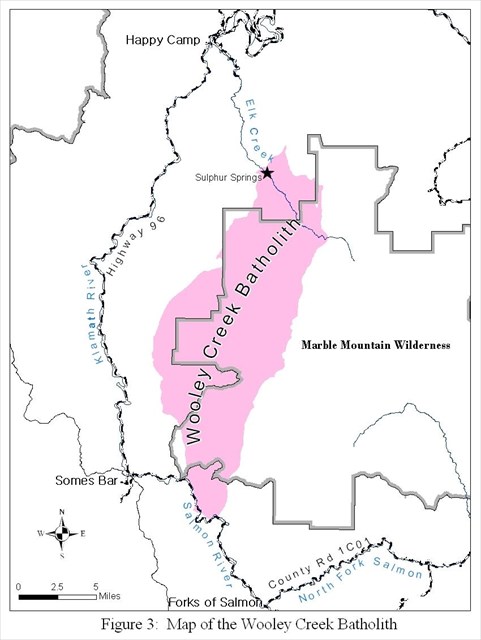

Wooley Creek Batholith is located in the Salmon/Scott River Ranger District.

In order to get to Wooley Creek Batholith you will take County Road 1C01, the site is 10 miles from Forks of Salmon and 6.7 miles from Highway 97. UTM Location: 10T 0456978, 4577559 NAD 83.

Geological Information

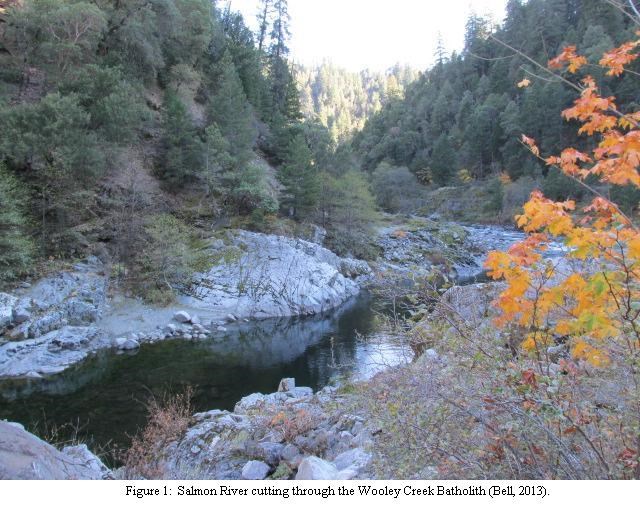

The Wooley Creek Batholith is located in the Salmon/Scott River Ranger District of the Klamath National Forest along the Salmon River in the Klamath Mountains Province. The mountains are made up of Paleozoic and Triassic rocks which represent a past of subduction and accretion. The Wooley Creek Batholith is exposed in many places of the Klamath National Forest, including along the Salmon River where the Earth Cache site is found (Figure 1).

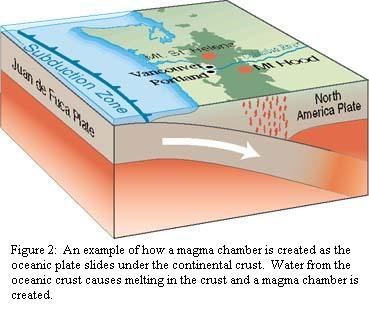

Subduction is the process of an oceanic plate scraping under continental crust on its way back into the mantle. Parts of the oceanic plate are scraped off and accreted (added on) to the continental crust. Much of California was created by adding on the ocean sediments to the existing continental crust.

Magma is produced when water from the subducting oceanic plate causes partial melting in the continental crust. The molten rock squeezes through weak areas in the crust, pushing up through the crust, creating a magma chamber (Figure 2). Room is made for the growing magma chamber by some of the wall rock collapsing into the magma this is called stoping. Eventually the magma chamber starts cooling and solidifying and this large body of rock is called a batholith.

The Wooley Creek Batholith intruded into Northern California in the Jurassic period about 162 million years ago and continued forming until 150 million years ago. The batholith was then cut off from its heat source by a new plate subducting and accreting land on to the west coast, cooling and solidifying.

Magma chambers are formed 3 – 25 miles (5 – 40 km) below the surface, so when they are molten, they are deep in the crust. After millions of years of erosion, the Wooley Creek Batholith has been exposed and is approximately 80,000 acres (Figure 3).

As you investigate the batholith alongside the river, look upstream and downstream. The Salmon River is eroding down into the Wooley Creek Batholith all along the valley. Now take a look at the rock making up the batholith. There is a striking joint pattern in the formation. Joint sets are a group of fractures with the same direction or orientation. If you look to the opposite bank that you are standing on, you can find similarly oriented joints?

There are three different types of rocks within the batholith: felsic rocks, mafic rocks and xenoliths. Overall the rock looks white which is due to the abundance of plagioclase (white, equant crystals) and grey grains of quartz. This rock is called a granodiorite and is known as felsic rock (an igneous rock with light-colored minerals). The dark minerals in the granodiorite are hornblende and biotite. Most of the hornblende is euhedral (well developed crystal shape) elongate, black crystals. The biotite is a dark root beer color with a platy texture that forms “books” or layers. There may also be small amounts of apatite, alkali feldspar or zircon. The grains of this rock can easily be seen without the aid of a hand lens, so it would be called phanaritic.

Can you find any dark blobs of rock within the granodiorite? These dark areas are generally rounded in this part of the batholith, but toward the northeast of the batholith, they become more tabular. There are different types of blobs present in the batholith: a dark grey, mafic hornblende-rich rock and metasedimentary xenoliths (foreign rocks in the magma chamber such as wall rock). These blobs of dark rock can range in size from less than 4 inches (10 cm) up to 65 feet (20 m). That’s longer than a city bus!

The mafic rocks are rich in magnesium and iron and have a dark grey to black color. The main body of the rock is felsic which refers to the light colored minerals like plagioclase and quartz. If you look closely at the mafic rocks, can you see individual crystals? Euhedral hornblende crystals and plagioclase can be seen with the naked eye within a groundmass of crystals that are too small to see without the aid of a hand lens. This is known as a porphyritic texture. This type of texture means that the magma cooled slowly at first so the larger crystals could grow, the crystals that make up the groundmass are very fine grained, which shows it cooled more quickly perhaps as a result of the magma chamber being closer to the surface due to erosion.

Metasedimentary xenoliths are a metamorphosed sedimentary foreign rock or a rock not formed within the batholith. An example may be a chunk of wall rock that fell into the magma during emplacement. Some of the metasedimentary xenoliths may even still show bedding or foliation.

Another feature of the batholith is that it is cross-cut by many granitic and basaltic dikes. Look at the textures of the white veins, how does the texture compare to the granodiorite? Can you identify any of the minerals? These are granitic in composition, so you should be able to see some plagioclase and quartz. The basaltic dikes are mafic and a dark grey color containing crystals of plagioclase, hornblende and biotite. Some of these dikes have uneven contacts with the granodiorite.

Logging Questions

Describe the joint sets: which direction are they trending? Are they steep or shallow? How far apart are they? At what angle do the joints intersect?

Are the grain sizes different between the mafic enclaves and the granodiorite? What does this tell you about the rate of cooling?

How many different types of rocks discussed above can you find?

References:

Barnes, C.G., 1983, Petrology and upward zonation of the Wooley Creek Batholith, Klamath Mountains, California, Journal of Petrology, Volume 24, Issue 4, p. 495 – 537.

Barnes, C.G., 1987, Mineralogy of the Wooley Creek batholith, Slinkard pluton and related dikes, Klamath Mountains, northern California, American Mineralogist, Volume 72, p. 879 – 901.

Harden, D.R., 2004, California geology, Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J., 552 p.

Kearey, P., 2001, Dictionary of Geology, Penguin Books, London, 327 p.

Image references:

Subduction: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/glossary/?term=subduction%20zone

Contacts:

Salmon/Scott River Ranger District

11263 N. Highway 3

Fort Jones, CA 96032-9702

(530) 468-5351

FAX (530) 468-1290

TDD (530) 468-1298

Klamath National Forest

Supervisor’s Office

1711 South Main Street

Yreka, CA 96097-9549

(530) 842-6131

FAX (530) 841-4571

TDD (530) 841-4573