MILANO: CITTA' D'ACQUA

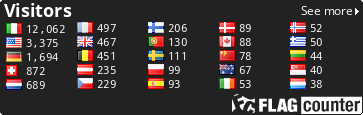

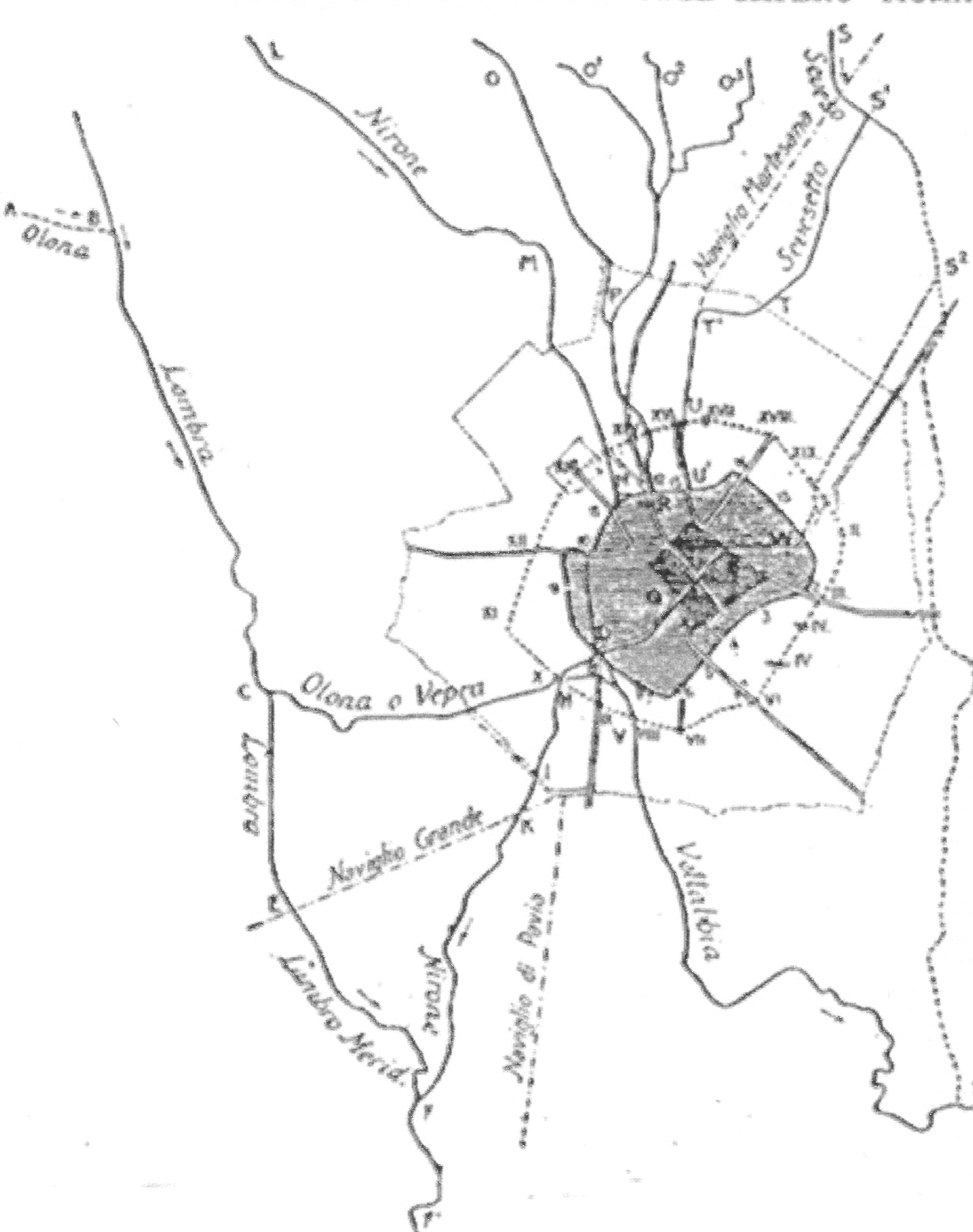

L'idrografia milanese, nonostante appaia relativamente semplice, è in realtà molto complessa poiché tra canali, fiumi, torrenti e rogge c'è un vero e proprio groviglio idrico che è impossibile descrivere senza intrecciare, alla natura dei luoghi e delle acque, gli interventi umani nel corso di più di due millenni.

Da oriente in senso antiorario abbiamo il Lambro, il Martesana-Seveso, l'asse Olona-Lambro meridionale, il Naviglio Grande e il Naviglio Pavese.

Nonostante quindi in superficie siano visibili principalmente questi corsi d'acqua, sul territorio comunale di Milano il reticolo di corsi d'acqua naturali e artificiali ereditati dal passato ha uno sviluppo complessivo di 370 chilometri (circa 200 relativi a corsi minori), gran parte dei quali in alvei sotterranei.

| Fiumi |

Torrenti |

Canali |

| Olona, Lambro Settentrionale |

Seveso, Fugone, Lura, Pudiga, Garbogera |

Deviatore Fiume Olona, Cavo Redefossi, Grande Sevese |

|

|

| Colatori |

Navigli |

| Lambro Meridionale |

Pavese, Martesana, Grande |

|

|

|

|

| Rogge |

Cavi |

Fontanili |

| Vettabbia alta, Vettabbia bassa, Carlesca, Triulza, Gerenzana, della Conserta, Dardarona, Boccafoppa, delle Cime, Paimera, Borrona, Misericordia, Cava, Spazzola, Molina, Bordone, Desa, Parasacco, Campazzino, Fuga, Malghera, Guardina, Ohman, Cornice, Reggina, Inferno, Bozzolo |

Lambretto, Ticinello, Sala, da Sesto, Taverna, Bolagnos, Cornice, Parea, Bissone, Melzi, Loreto |

Bicocca, Giglio, Cavetto Nuovo, Togliolo, Rile, Molla di S. Carlo, Bocchetta del Seminario |

(Principali corsi d'acqua che interessano il milanese)

STRUTTURA IDROGEOLOGICA

La città poggia su rocce di origine fluvio-glaciale a cemento carbonatico, comune a tutta la pianura padana, la cui caratteristica principale è quella di essere facilmente carsificabile. Posizionandosi in piena "linea delle risorgive", laddove cioè vi è l'incontro, nel sottosuolo, tra strati geologici a differente permeabilità, le acque profonde possono riaffiorare in superficie tramite risorgive e fontanili (attualmente più di 400 in provincia di Milano).

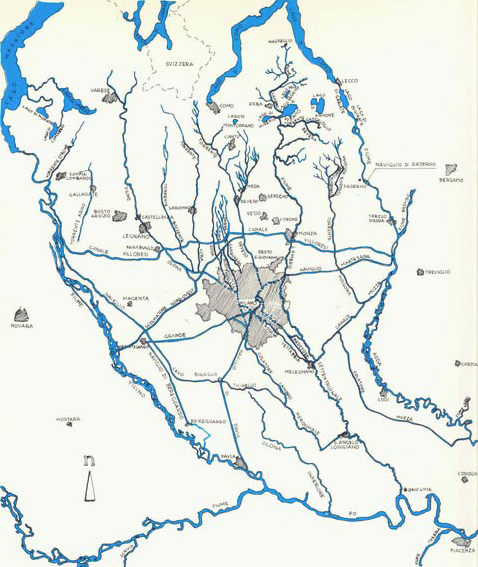

Il sottosuolo dell'area milanese può essere suddiviso in tre principali distinte unità idrogeologiche (Avanzini et a.) aventi nel loro insieme caratteri litologici e idraulici ben riconoscibili e distribuiti con omogeneità su settori significativi.

La prima unità è costituita da sedimenti fluvioglaciali “ghiaioso-sabbiosi”, affioranti in superficie e risalenti al Pleistocene Superiore, sino a 40-50 metri di profondità, ai quali si sostituiscono progressivamente sedimenti “ghiaioso-sabbiosi-limosi” (seconda unità, risalenti al Pleistocene Medio) che si estendono sino a una profondità di circa 100 metri.

Le falde, libere e semiconfinate, contenute in questo acquifero (“acquifero tradizionale”) hanno costituito la risorsa idrica storicamente sfruttata dalla città.

La falda libera è separata dalla sottostante falda semiconfinata per mezzo di un livello argilloso di spessore di qualche metro, distribuito con buona continuità laterale su tutta l’area. Dal punto di vista idraulico le due unità sono comunque in parte comunicanti e si caratterizzano quindi come un unico grande sistema multifalda.

Le falde profonde sottostanti sono invece contenute in sedimenti "sabbioso-argillosi" (d'origine continentale, risalenti al Pleistocene Inferiore) o argillosi (d'origine marina, risalenti questi al Calabriano) che rappresentano la terza unità idrogeologica locale.

Queste falde, caratterizzate da produttività idriche limitate e quindi attualmente poco sfruttate, sono idraulicamente separate da quelle più superficiali.

Da un punto di vista più strettamente idrogeologico si possono distinguere tre acquiferi definiti in base alle caratteristiche di permeabilità dei sedimenti:

Primo acquifero: costituito da depositi alluvionali recenti ed antichi e dal fluvioglaciale wurmiano; si tratta di sedimenti (ghiaie e sabbie prevalenti) ad elevata permeabilità;

Secondo acquifero: costituito da depositi fluvioglaciali antichi, con sedimenti (ciottoli, ghiaie e sabbie in matrice limosa) di medio–alta permeabilità localmente cementati, con spessori variabili che possono arrivare a 40–50 metri;

Terzo acquifero: costituito da depositi a granulometria prevalentemente fine con permeabilità medio–bassa.

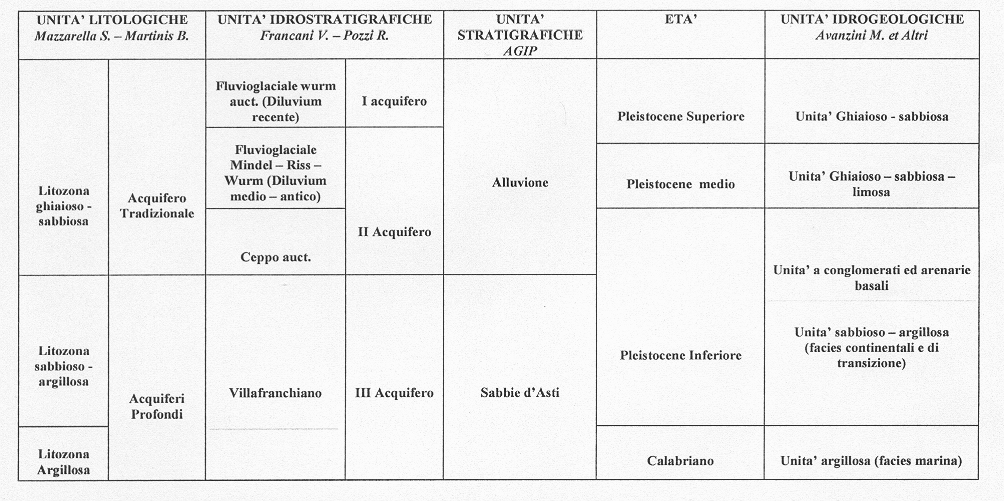

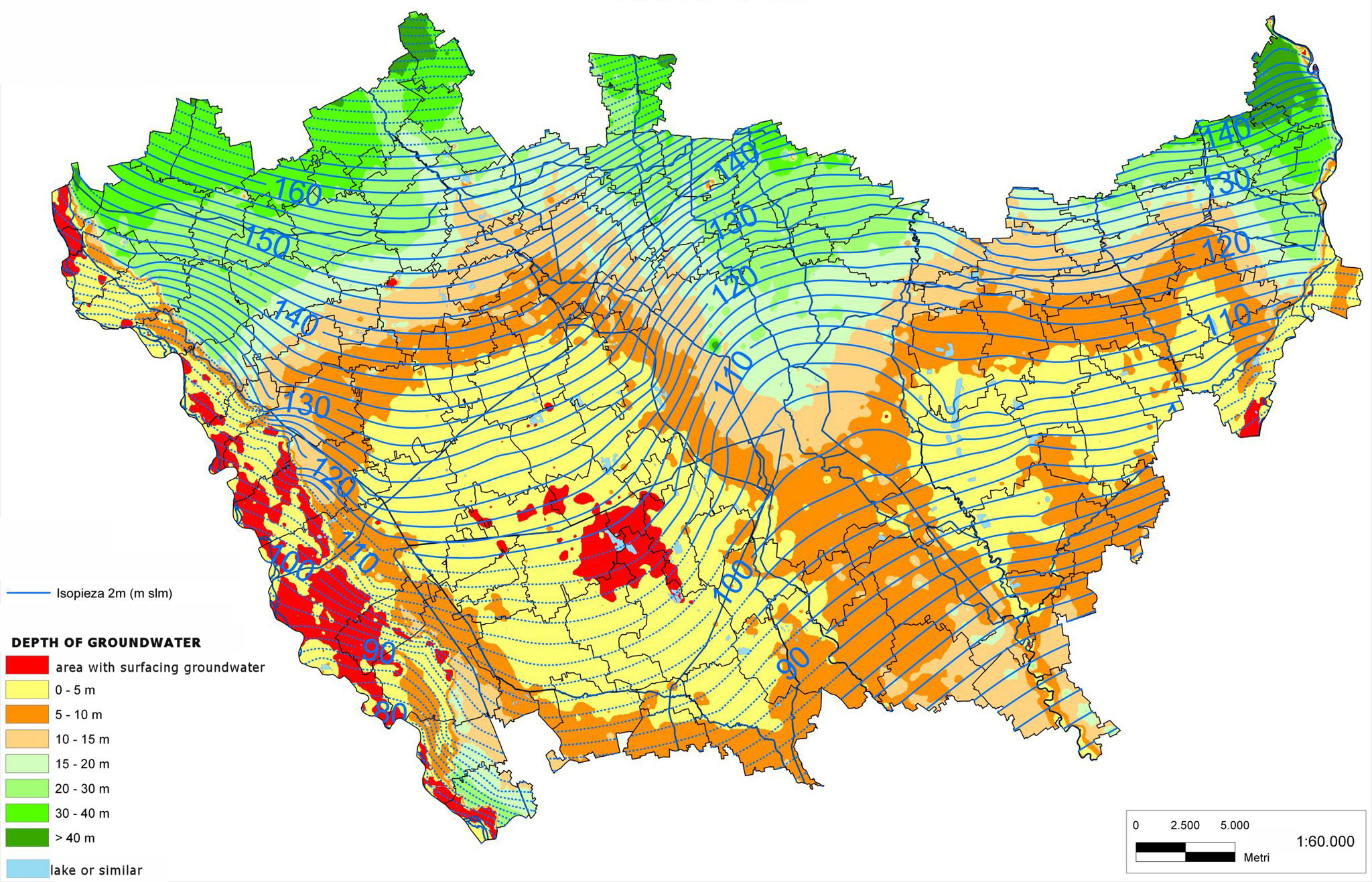

Per avere un quadro dell'andamento della falda nell'area del milanese si veda la carta della piezometria e soggiacenza della falda elaborata dalla Provincia di Milano.

Si notano le differenze di gradiente idraulico tra l'area settentrionale e quella centro-meridionale, l'effetto drenante dei principali corsi d'acqua e l'inflessione delle linee di flusso idrico al margine occidentale dell'area.

Per quanto riguarda la soggiacenza della falda si va da valori massimi di oltre 16 metri al confine nord dell'area a minimi inferiori a 4 metri nelle zone centrali di emergenza. Sono inoltre presenti piccole falde assai più superficiali.

Strettamente connesso con situazioni di falda molto superficiale è il fenomeno dei fontanili, legato a un insieme di fattori idrogeologici il principale dei quali è la riduzione, passando da nord a sud, delle granulometrie dei materiali in cui la falda è contenuta, con la conseguente formazione di sorgenti per sbarramento ed emergenza.

Nonostante la fuoriuscita dell'acqua sia sempre stata favorita dall'uomo per l'utilizzo a scopi irrigui (marcite), la persistenza dei fontanili è soprattutto legata alla presenza di una falda sub-superficiale.

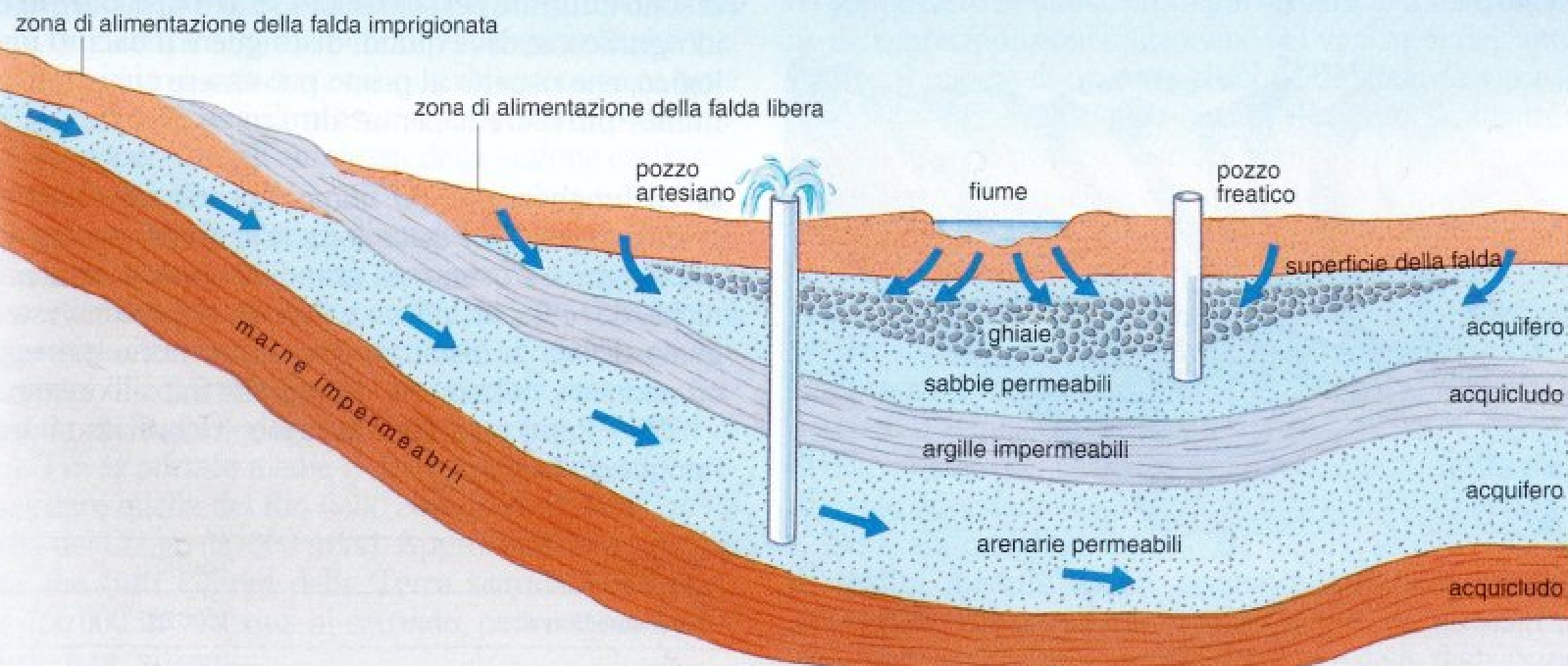

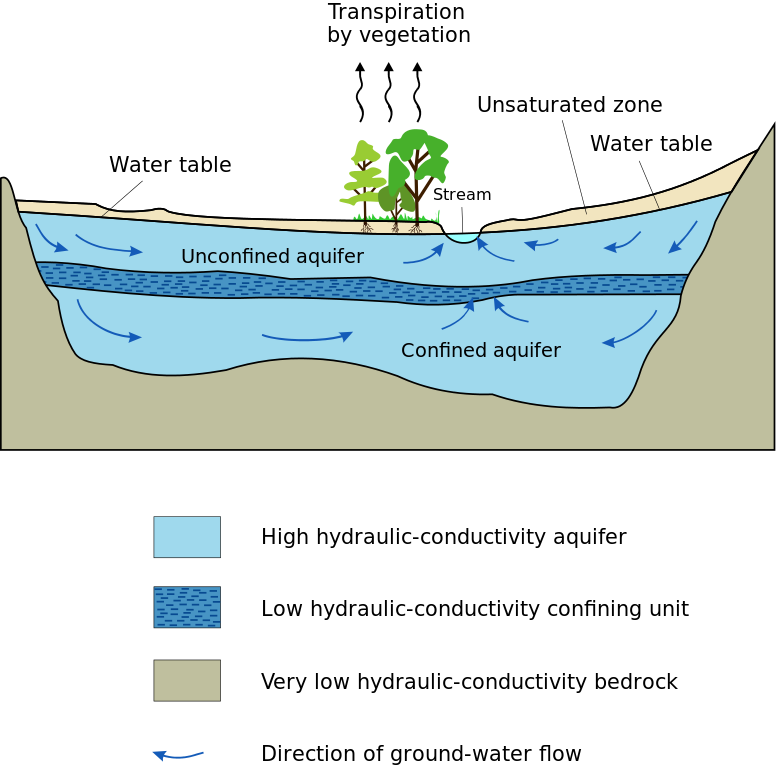

CARATTERISTICHE GENERALI DI UNA FALDA

Le falde freatiche sono accumuli di acqua superficiali che si formano grazie alla presenza di uno strato impermeabile sottostante, a volte estese per anche molti chilometri e che possono terminare in un fiume, in un lago o direttamente in mare. Quando la parte superficiale della falda incontra il profilo del terreno l'acqua emerge sotto forma di sorgente.

Nelle falde freatiche l'acqua si infiltra nel sottosuolo tramite terreni permeabili o tramite fratture o fessure, scendendo poi in profondità ad occupare un certo quantitativo di rocce e sedimenti, riempiendo le fessure e i pori tra le particelle, fino a quando non incontra un terreno impermeabile (tipicamente rocce compatte non fessurate e argille).

(Schema delle falde; l'acquifero superiore è la falda freatica, l'acquifero inferiore la falda artesiana)

Differenti dalle falde freatiche vi sono quelle artesiane, solitamente situate a maggiori profondità e delimitate da due strati impermeabili, uno sotto ed uno sopra; queste sono più protette dagli agenti inquinanti e hanno sufficiente pressione a far zampillare l'acqua da sola in superficie senza bisogno di pompaggio, tramite un pozzo artesiano.

SE LA FALDA VARIA, COSA SUCCEDE?

Nella seconda metà del XX secolo la falda del sud-est milanese fu oggetto di alcune importanti fluttuazioni che causò pesanti ripercussioni sulla popolazione e sull'ambiente.

Fino ai primi anni 1950 la superficie della falda aveva conservato una posizione molto vicina al suolo, a uno o due metri di profondità, alimentata dai fontanili presenti nella zona, la quale aveva una vocazione prevalentemente agricola. Successivamente, l'intenso sviluppo industriale e urbanistico degli anni 1950-70 diede luogo ad un crescente prelievo di acque che impoverì gli acquiferi e causò l’abbassamento della falda fino a 40 metri nella zona centrale di Milano. In conseguenza del disseccamento e della compattazione dei terreni abbandonati dall'acqua si manifestarono locali fenomeni di abbassamento del suolo, con valori di 22 cm in zona Duomo.

(Falda acquifera e manufatti tra il 1950 e il 1996 - si noti la posizione della Metropolitana M3 a destra)

La falda acquifera rimase depressa fino alla metà degli anni 1970, quando la dinamica si invertì bruscamente in seguito alla chiusura di molti pozzi dismessi in conseguenza del trasferimento nel nord milanese delle industrie.

Si ebbe una drastica diminuzione dei prelievi idrici che causò una risalita della falda di anche una decina di metri, provocando l’inondazione di molti edifici seminterrati.

(Risalita della falda dal 1972 al 1997 lungo la sezione da Milano a Melegnano)

Lo stesso innalzamento della falda continua a provocare anche oggi, in concomitanza di piogge importanti e nel periodo autunnale e invernale, allagamenti frequenti e infiltrazioni nelle linee della metropolitana milanese dove la falda sale e si infiltra attraverso le pareti di cemento.

L'IDROGRAFIA MILANESE NELLA STORIA

Dal momento che è impossibile descrivere l'idrografia milanese senza tener conto dell'intervento umano, qui di seguito verranno riportati i principali interventi antropici alla natura dei luoghi e delle acque, a coprire più di duemila anni di storia.

EPOCA ROMANA E PRE-ROMANA

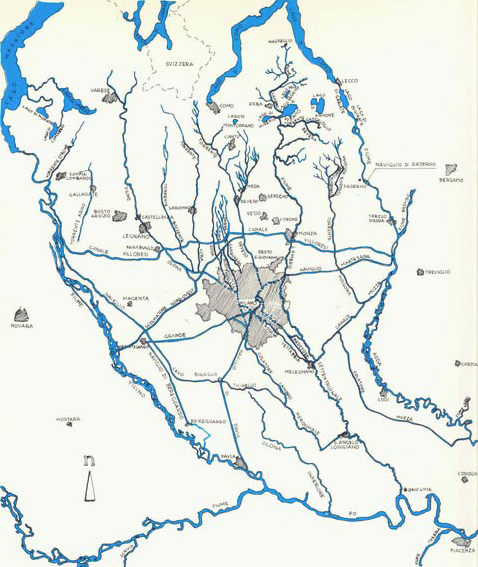

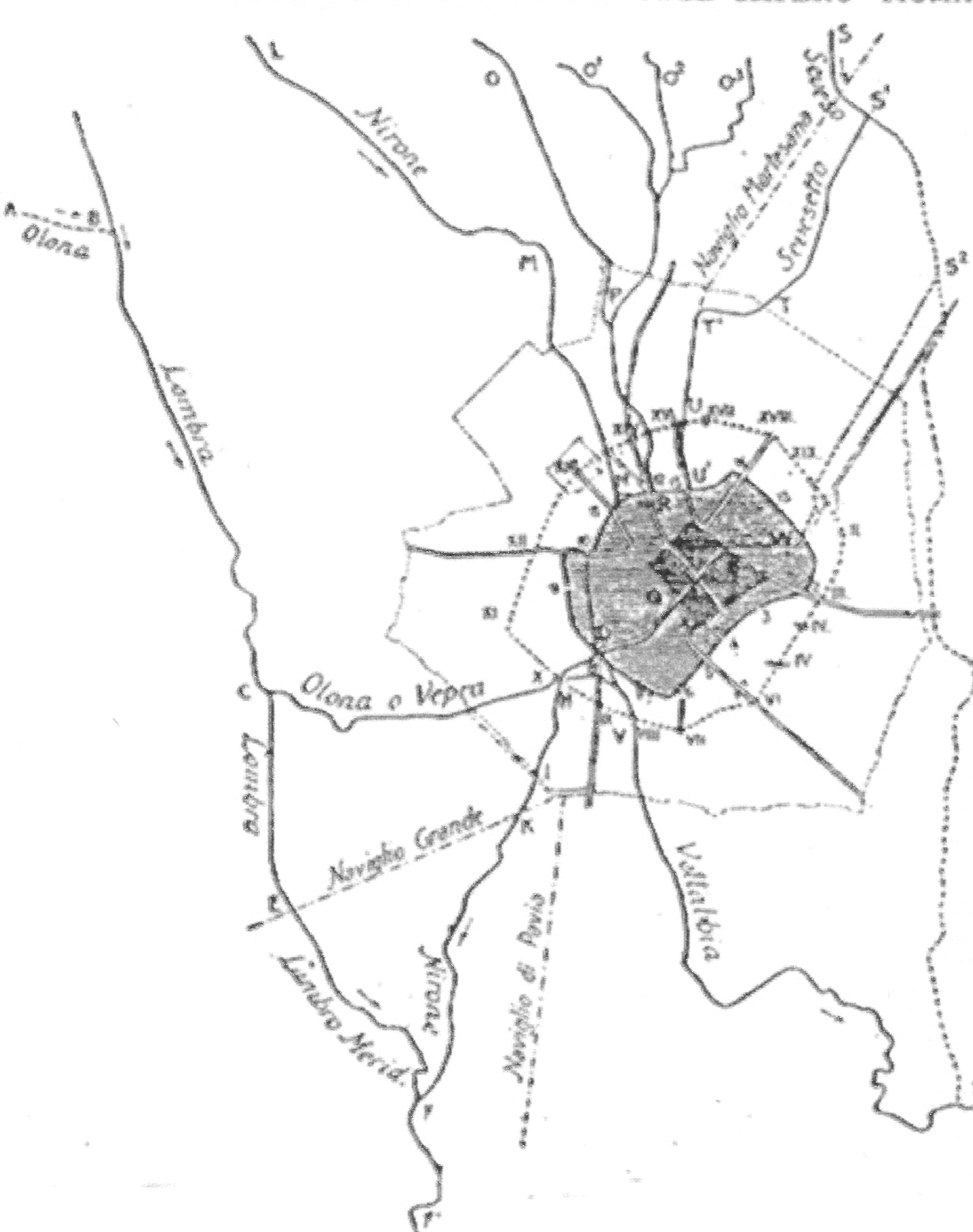

(Idrografia in epoca romana)

Nell'epoca pre-romana, ai tempi dell'insediamento gallo-insubrico cui si fanno risalire le origini di Milano (V secolo a.C. circa), la città aveva un solo fiume che la interessava direttamente, quello che i romani più tardi chiamarono Nirone, e un fontanile, il Molia.

Il Nirone nasceva tra le odierne piazza Firenze e piazzale Accursio, mentre il Molia sgorgava poco lontano e raccoglieva da nord alcune rogge; entrambi scorrevano a sud nella fascia di territorio compresa tra l'Olona, a ovest, e il Seveso, a est.

Non vi erano canali, ma essendo Milano al centro della fascia delle risorgive il territorio era ricchissimo d'acqua e, per praticare l'agricoltura e per muoversi in un terreno altrimenti paludoso, gli abitanti dovettero regolarizzare le acque ricorrendo a canalizzazioni e drenaggi, cui si sovrapposero poi opere successive.

Il grosso delle bonifiche e delle modifiche agli alvei dei fiumi avvenne in epoca romana, a partire dal 222 a.C.: le campagne circostanti Mediolanum vennero assegnate a coloni e a reduci, che ne attuarono la bonifica. Da una parte si raccolse l'acqua per asciugare i terreni, dall'altra si usarono raccolte per irrigare con un reticolo fittissimo di fossi, canaletti, ruscelli che rimarrà nei secoli la caratteristica di Milano e del Milanese.

Tra il finire dell'era repubblicana e i primi secoli di quella imperiale i romani realizzarono altre opere ben più appariscenti che modificarono radicalmente l'idrografia milanese: la deviazione del Seveso e lo scavo della Vettabbia, una seconda deviazione del Seveso e la deviazione dell'Olona.

Necessitando di una maggiore quantità d'acqua si iniziò a portare in città il Seveso tramite un canale, il Grande Sevese, che giungeva alla Vetra ed esiste ancora oggi, andando dal Redefossi al Cavo Ticinello, sotto le vie dell'Orso, Monte di Pietà, Monte Napoleone, Larga, Disciplini, piazza Vetra. Tramite la Vettabbia, sfociante nel Lambro a Melegnano, si poteva navigare fino al mare scendendo lungo l'asta del Po.

Lungo le mura occidentali si trovavano le acque, anch'esse deviate, del Nirone, del Molia e delle rogge che, tramite poi un colatore, diventavano il Lambro meridionale. L'Olona venne deviato in zona Rho dal suo alveo naturale e portato fino nella Vettabbia, perdendo quindi la propria foce naturale.

DALLE INVASIONI BARBARICHE AL XIII SECOLO

Durante le invasioni barbariche il complesso intrico di bonifica e irrigazione attorno alla città decadette, lasciando il posto alla boscaglia e alla palude. Fu solo nel XII secolo che i monaci di Chiaravalle e di Morimondo ripristinarono i coltivi e i prati a marcita.

Nel frattempo, nel 1152, si era costruito un canale che deviava le acque del Ticino alla bassa pianura: era il Ticinello, che da Abbiategrasso a Landriano esiste ancora oggi. Nel 1272 il Ticinello divenne il Naviglio Grande: il canale era navigabile e arrivava ai margini della città, a Sant'Eustorgio, di fondamentale importanza per lo sviluppo dei commerci e della potenza di Milano.

Da Milano l'acqua del Ticino riprendeva la via delle campagne attraverso un nuovo Ticinello: dimenticato il primo così si chiamò un nuovo canale che sfociava verso Selvanesco (oggi un quartiere della periferia meridionale di Milano) a irrigare i terreni dei nuovi signori della città, i Torriani.

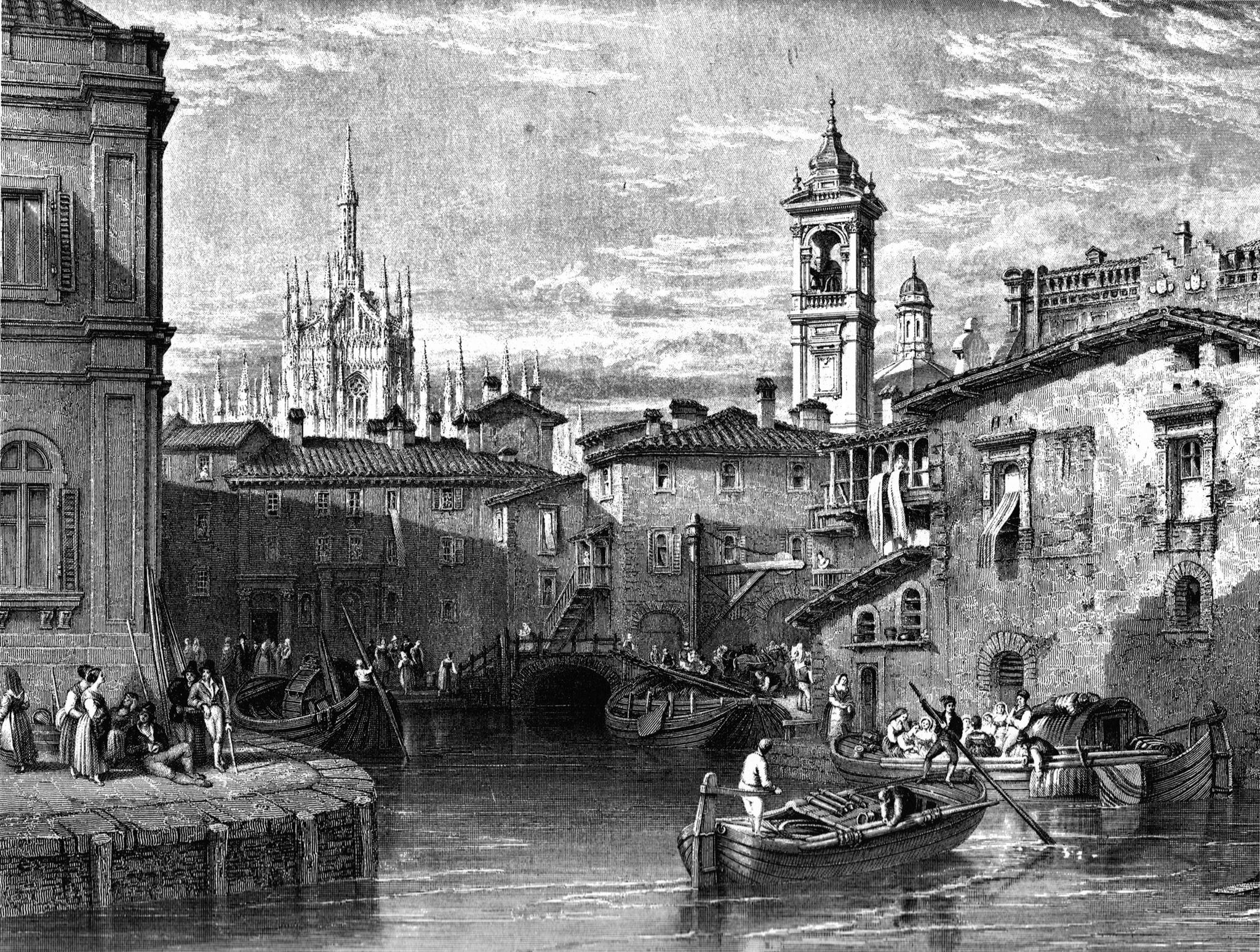

I VISCONTI E GLI SFORZA

Nel 1359 Galeazzo II Visconti ordinò la costruzione di un naviglio per Pavia, allo scopo di irrigare il parco che dal castello arrivava fino oltre l'attuale Certosa e un altro aqueducto per irrigare, partendo dall'Adda, una tenuta similare attorno al castello di porta Giovia a Milano. Il primo era il Navigliaccio, mentre del secondo non restano tracce.

Fu poi solo in seguito che Gian Galeazzo Visconti volle per la sua città una cattedrale degna di rivaleggiare con le maggiori d'Europa. Progettata interamente in marmo questo arrivava, attraverso il Naviglio Grande, direttamente dalle cave di Candoglia, sulla sponda occidentale del Verbano.

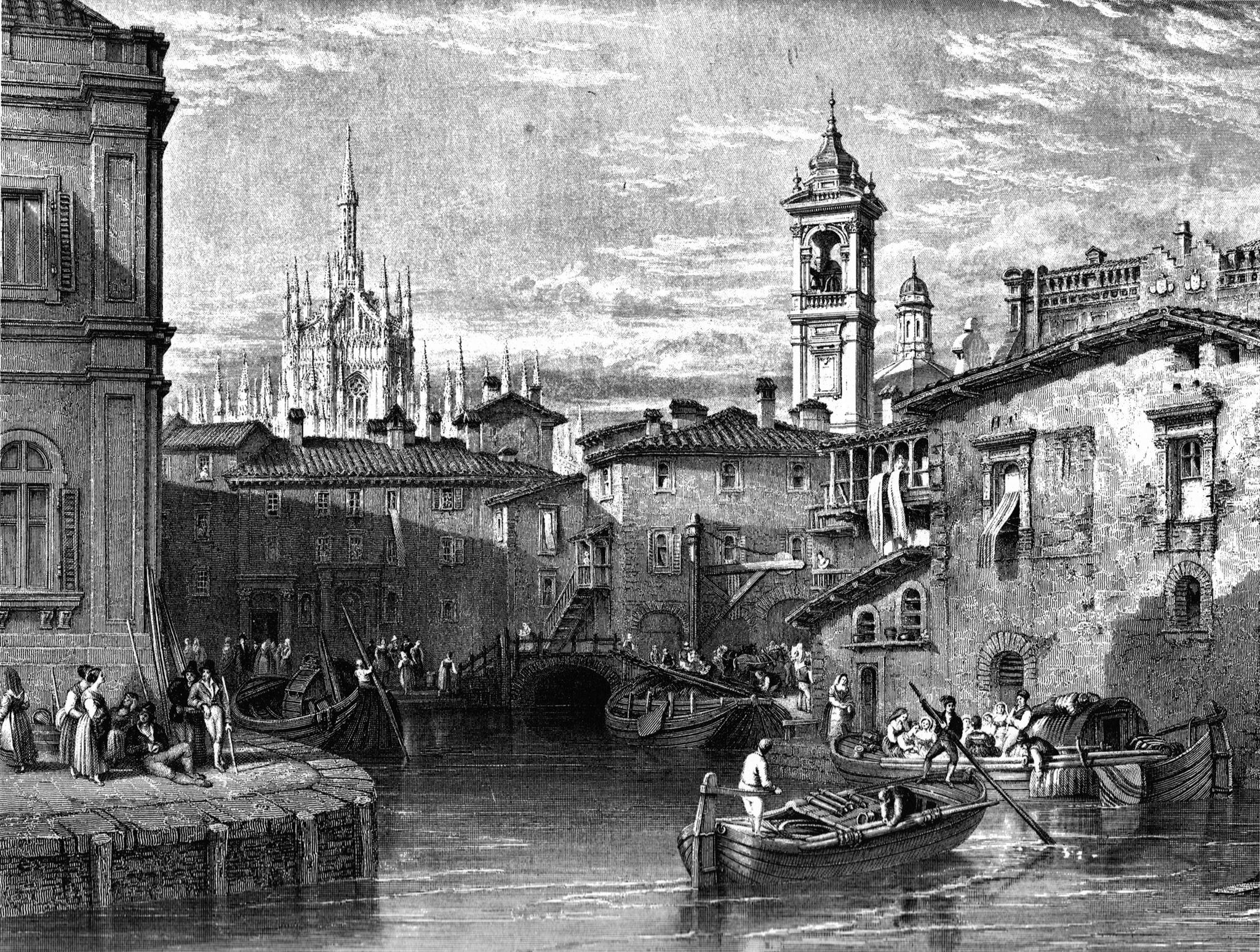

Si rese così navigabile la fossa che cingeva le mura, si prolungò fino a essa il Naviglio e si scavò un approdo (il laghetto di Santo Stefano) dove arrivavano tutti i materiali da costruzione necessari per costruire il Duomo.

(Laghetto Santo Stefano)

Cinquant'anni dopo, sul tratto d'acqua che congiungeva Sant'Eustorgio alla fossa interna, venne realizzata la prima conca, sotto il dominio di Filippo Maria Visconti.

Sarà il suo successore, Francesco Sforza, a fare costruire il Naviglio della Martesana, da Trezzo d'Adda alla Cassina de' pomm.

DALLA DOMINAZIONE SPAGNOLA ALL'INIZIO DEL 1800

Della lunga dominazione spagnola sulla carta idrografica di Milano resta la Darsena, realizzata dal 1603 al 1605 con la deviazione dell'Olona che ne divenne diretto tributario, e lo spostamento della conca di Viarenna.

Ci saranno gli Austriaci a capo del ducato quando si compirono invece i lavori per il Naviglio di Paderno nel 1777 e quando si realizzò il Redefossi; sempre sotto il dominio austriaco si inaugurò la navigazione sul Naviglio Pavese nel 1819.

IL VILLORESI, "PORTO DI MARE" E LA COPERTURA DEI NAVIGLI

(Il naviglio in via Fatebenefratelli)

Il canale Villoresi venne infine realizzato tra il 1877 e il 1890, quando in città era già stato interrato il laghetto di Santo Stefano e coperte diverse rogge.

Degno di menzione, anche se mai costruito, è Porto di Mare, l'infrastruttura che avrebbe dovuto consentire la sopravvivenza del sistema idroviario di Milano; secondo un progetto del 1917 nella zona tra Corvetto e i confini della città doveva essere collocato il porto destinato a sostituire la darsena di Porta Ticinese, ma i lavori non furono mai conclusi.

Di questo progetto rimane oggi solo il nome dell'omonima stazione della Metropolitana.

Il 3 marzo 1928 venne richiesto il permesso di copertura della cosiddetta "fossa interna", ossia del tratto di naviglio da Piazza San Marco fino a Porta Genova, motivata da nuove necessità viabilistiche ed igieniche. La copertura dei navigli avvenne tra il 1929 e il 1930, creando un anello di strade che ne prese il posto e che fu chiamato Cerchia dei Navigli, il quale divenne la circonvallazione interna di Milano, benché già all'epoca venisse definito "cappio al collo", anziché "anello", per via del suo brevissimo raggio, che portava il traffico automobilistico in centro città.

(Copertura del naviglio in via Senato)

ROGGIA VETTABBIA

La Roggia Vettabbia, come detto precedentemente, è un corso d'acqua tradizionalmente molto importante per il suo apporto di acque irrigue all'area agricola a sud di Milano ed è anche quello che accoglie il maggior contributo di acque fognarie cittadine.

Essa nasceva originariamente dalla fossa interna dei navigli, presso via Molino delle Armi.

Ora riceve acque naturali dal canale di San Marco e dal Seveso oltre alle acque di scarico (depurate) della fognatura comunale.

Scorre coperta fino a via Carlo Bazzi, e all'altezza di via Castelbarco riceve il grande collettore fognario chiamato Gentilino, che serve buona parte del centro storico della città.

Successivamente, dopo via Ripamonti, prima di raggiungere viale Ortles, riceve un secondo grande innesto, rappresentato dal collettore Vigentino, che serve anch'esso il centro storico.

A valle di questa immissione si trovano le prime derivazioni irrigue di una certa importanza, raggiungendo poi la zona di Nosedo e dando così origine ad altre rogge e ricevendo inoltre l'apporto del collettore di Nosedo, il principale collettore della rete fognaria milanese, e di altri due collettori minori, provenienti dalle vie Ripamonti, San Dionigi e Sant'Arialdo.

Alimenta poi con varie derivazioni un vasto comprensorio agricolo avente una superficie di circa 3700 ettari e sfocia infine nel Lambro a monte di Melegnano.

(La "valle" della Vettabbia)

Profondamente modificata dall’intervento antropico la valle fluviale, originariamente scavata dalle acque del Seveso, è attualmente ancora percepibile solo in piccola parte; pur nel recente processo di livellamento del suolo, infatti, una lieve depressione testimonia ancora della sua presenza.

Proprio la presenza della Vettabbia, il flumen mediolanensis, è stata determinante per la localizzazione nel XII secolo dei complessi abbaziali di Chiaravalle Milanese e di Viboldone, costituendone la ragione insediativa fondamentale e divenendo in breve tempo la vera e propria “spina dorsale” delle loro vaste possessioni.

Il ricco patrimonio di fossi, canali collettori e sistemi di drenaggio è sicuramente dovuto alla complessa operazione di estensione e riorganizzazione della rete irrigua compiuta dai monaci.

(Roggia Vettabbia nel 1880)

EARTHCACHE

Per poter registrare come "found" questa earthcache devi rispondere alle seguenti domande:

1) Visto quanto detto finora, che tipo di falda è quella che provoca gli allagamenti nella metropolitana milanese?

Recati ora alle coordinate indicate dal listing: sotto la strada, facilmente visibile, vi è il corso della Roggia Vettabbia.

2) Qual è la larghezza del corso d'acqua (in metri)?

3) Come ti sembrano visivamente e olfattivamente le acque della roggia? Apparentemente limpide o torbide? Inquinate o pulite?

4) OBBLIGATORIO: fatti una foto o falla al tuo GPS/smartphone/nickname (a scelta) nel luogo della EC

Si prega di non scrivere le risposte nel log, ma di inviarle attraverso il mio profilo su geocaching.com.

Puoi fare il log quando hai inviato le risposte, senza aspettare la mia conferma.

Se le tue risposte sono sbagliate ti contatterò.

MILAN: CITY OF WATER

The hydrography of Milan, although it appears relatively simple, it is actually very complex because between canals, rivers, streams and ditches there is a real tangle water that is impossible to describe without interweaving, to the nature of places and waters, human interventions over more than two millennia.

From east counterclockwise we have Lambro, Seveso-Martesana, Lambro Meridionale-Olona axis, Naviglio Grande and Naviglio Pavese.

Therefore, despite on the surface are visible mainly these waterways, in the Municipality of Milan the pattern of natural and artificial rivers inherited from the past has a total length of 370 kilometers (about 200 related to minor courses), most in underground ways.

| Rivers |

Streams |

Canals |

| Olona, Lambro Settentrionale |

Seveso, Fugone, Lura, Pudiga, Garbogera |

Deviatore Fiume Olona, Cavo Redefossi, Grande Sevese |

|

|

| Drain ditches |

Navigli |

| Lambro Meridionale |

Pavese, Martesana, Grande |

|

|

|

|

| Ditch |

Cable |

Springs |

| Vettabbia alta, Vettabbia bassa, Carlesca, Triulza, Gerenzana, della Conserta, Dardarona, Boccafoppa, delle Cime, Paimera, Borrona, Misericordia, Cava, Spazzola, Molina, Bordone, Desa, Parasacco, Campazzino, Fuga, Malghera, Guardina, Ohman, Cornice, Reggina, Inferno, Bozzolo |

Lambretto, Ticinello, Sala, da Sesto, Taverna, Bolagnos, Cornice, Parea, Bissone, Melzi, Loreto |

Bicocca, Giglio, Cavetto Nuovo, Togliolo, Rile, Molla di S. Carlo, Bocchetta del Seminario |

(Main waterways in Milan)

HYDROGEOLOGICAL STRUCTURE

The city rests on rocks of fluvial-glacial carbonatic concrete, common to the entire Po Valley, whose main feature is that it is easily carsificable. By positioning in full "line of springs", that is where there is a meeting, in the subsurface, between geological layers with different permeability, deep water may appear on the surface through springs and fountains (currently more than 400 in the province of Milan).

The subsoil of Milan can be divided into three main distinct hydrogeological units (Avanzini et al.) with a whole lithological and hydraulic recognizable characters and distributed homogeneously on significant sectors.

The first unit consists of fluvioglacial "gravelly-sandy" sediments, emerging on the surface and dating Upper Pleistocene, up to 40-50 meters deep, being superseded gradually by "gravelly-sandy-loamy" sediments (second unit, dating Middle Pleistocene) which extend to a depth of about 100 meters.

Groundwaters, free and semiconfinate, in this aquifer ("traditional aquifer") have historically been the source of water used by the city.

The free aquifer is separated from the underlying aquifer semi-confined by means of a clayey layer of a thickness of a few meters, distributed with good lateral continuity over the entire area. From the hydraulic point of view the two units are however partly interconnected and are therefore characterized as a single large multi-layered system.

The deep aquifers below are contained in "sandy-clayey" sediments (of continental origin dating to Lower Pleistocene) or clayey (of marine origin, dating back to the Calabrian) representing the third local hydrogeological unit.

These strata, characterized by limited water productivity and therefore currently underused, are hydraulically separated from the more superficial.

From a point of view more closely hydrogeological you can distinguish three aquifers defined according to the characteristics of permeability of the sediments:

First aquifer: made up of ancient and recent alluvial deposits and fluvioglacial; these are sediments (gravels and sands prevalent) highly permeable;

Second aquifer: made up of ancient fluvioglacial deposits and sediments (pebbles, gravel and sand in silt matrix) medium-high permeable locally cemented, with thicknesses that can reach 40-50 meters;

Third aquifer: made up of predominantly fine granulometry deposits with medium-low permeability.

To get a picture of the trend of aquifer in the area of Milan, see the paper of piezometry and depth of groundwater drawn up by the Province of Milan.

You can see the differences of hydraulic gradient between the area north and south central, the draining effect of the main rivers and the inflection of the lines of the water flow at the western edge of the area.

With regard to the depth of groundwater it goes from a maximum of over 16 meters at the northern boundary of the area to lows of less than 4 meters in the central areas of phreatic emergency. There are also small area much more superficial.

Closely connected with situations of very shallow aquifer is the phenomenon of springs, tied to a set of hydrogeological factors the main being the reduction, going from north to south, of the grain size of the material in which the water table is contained, resulting in the formation of springs.

Although the water drainage is always been favored by man for irrigation purposes, the persistence of the springs is largely linked to the presence of sub-surface water.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A AQUIFER

The phreatic zone are accumulations of surface water that are formed due to the presence of a waterproof layer below, sometimes also extended for many kilometers and that can terminate in a river, into a lake or directly into the sea. When the surface of the aquifer meets the profile of the ground the water emerges in the form of source.

In phreatic zones water infiltrates into the ground through permeable soils or through fractures or cracks, then down deep to occupy a certain amount of rocks and sediments, filling the cracks and pores between particles, until it encounters an impermeable soil (typically fissured or not compact rocks and clays).

(Diagram of groundwater; the upper aquifer is the phreatic zone, the aquifer below the artesian)

Different from the phreatic zone there are artesian, usually found at greater depths and delimited by two impermeable layers, one below and one above; these are more protected from contaminants and have sufficient pressure to squirt water alone on the surface without the need for pumping, via an artesian well.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THE AQUIFER CHANGES?

In the second half of the twentieth century the aquifer of Southeast Milan was the subject of some major fluctuations which caused serious repercussions on the population and the environment.

Until the early 1950s, the surface of the aquifer had kept very close to the ground, one or two meters deep, fed by springs in the area, which was mainly devoted to agriculture. Later, the intense industrial and urban development of the years 1950-70 resulted in a growing withdrawal of water that impoverished aquifers and caused the lowering of the water up to 40 meters in the central area of Milan. As a result of drying and compaction of the soils abandoned by water local phenomena of ground subsidence manifested, with values of 22 cm in the Duomo area.

(Aquifer and artifacts between 1950 and 1996 - note the position of the subway M3 on the right)

The aquifer remained depressed until the mid-1970s, when the trend was reversed sharply following the closure of many wells decommissioned as a result of the transfer of industries in the north of Milan.

There was a drastic reduction of water withdrawal which caused a rise in the aquifer of about a dozen meters, causing flooding of basements of many buildings.

The raising of the water continues to provoke even today, in conjunction with major rains and during autumn and winter, frequent flooding and infiltration in the Milan subway lines where the water rises and seeps through the concrete walls.

HYDROGRAPHY OF MILAN DURING HISTORY

Since it is impossible to describe the hydrography of Milan without taking into account human intervention, we will be hereafter shows the main human interventions to the nature of the places and water, covering more than two thousand years of history.

ROMAN AND PRE-ROMAN PERIOD

(Hydrography in Roman times)

In pre-Roman times (fifth century BC), the city had only one river, what the Romans later called Nirone, and a spring, the Molia.

The Nirone born between today's Piazza Firenze and Piazzale Accursio, while Molia flowed nearby and picked up from the north some irrigation ditches; both flowed south in the strip of territory between the Olona, west, and the Seveso, east.

There were no canals, but being Milan in the center of springs area it was rich in water and, to practice agriculture and to move in an otherwise swampy terrain, the inhabitants had to regularize the water using pipes and drains.

The great majority of land reclamation and the modifications to the beds of rivers occurred in Roman times, from 222 BC: the surrounding countryside were assigned to settlers and veterans, who implemented the drainage. On one side they gathered the water to dry land, on the other the collected water was used to irrigate with a dense network of ditches, canals, streams that will remain for ever one of the characteristics of Milan.

Between the end of the republican era and the first centuries of the imperial Romans realized other works even more conspicuous that radically changed the hydrography of Milan: the deviation of the Seveso and the excavation of Vettabbia, a second deviation of the Seveso and the deviation of the Olona.

Needing a greater amount of water it was begun to bring the Seveso to the city by a canal, Grande Sevese, which came to the Vetra and still exists today, going from Redefossi to Cavo Ticinello under the streets dell'Orso, Monte di Pietà , Monte Napoleone, Larga, Disciplini, Piazza Vetra. Through Vettabbia, flowing into the Lambro in Melegnano, it could sail down to the sea along the shaft of the Po.

Along the western wall there were the waters, also diverted, of the Nirone, the Molia and the irrigation channels which, by an articulator, became the Lambro Meridionale. The Olona was diverted in Rho area from its natural channel and brought up to Vettabbia, thus losing its natural mouth.

FROM THE BARBARIAN INVASIONS TO XIII CENTURY

During the barbarian invasions the complex web of drainage and irrigation around the city was deserted, giving way to woods and swamp. It was only in the twelfth century that the monks of Chiaravalle and Morimondo restored the cultivated lawns and rotting.

Meanwhile, in 1152, a canal that diverted the waters of the Ticino to the lowlands was built: it was the Ticinello, from Abbiategrasso to Landriano, that still exists today. In 1272 the Ticinello became the Naviglio Grande: the canal was navigable, and came to the edge of town, in Sant'Eustorgio, crucial for the development of trade and for the power of Milan.

From Milan the water of Ticino resumed its way to the countryside through a new Ticinello: forgotten the first so it was called a new channel that flowed towards Selvanesco (now a district of the southern suburbs of Milan) to irrigate the land of the new lords of the city, Torriani.

VISCONTI AND SFORZA

In 1359 Galeazzo II Visconti ordered the construction of a canal to Pavia, in order to irrigate the park that from the castle came up to the present Certosa and another aqueducto to irrigate, starting from the Adda, a similar estate around the castle of Porta Giovia in Milan. The first was the Navigliaccio, while of the second no trace remains.

It was only later that Gian Galeazzo Visconti wanted for his city a cathedral worthy of rivaling the largest in Europe. Designed entirely of marble that came through the Naviglio Grande, directly from the quarries of Candoglia, on the western shore of the Verbano.

The ditch sorrounding the walls became so navigable, the Navigli was elongated till there and a landing place (the pond of Santo Stefano) was dug, where all the building materials required to build the Duomo came.

(Pond of Santo Stefano)

Fifty years later, on the waterfront that connected Sant'Eustorgio to the pit inside, the first basin was made, under the rule of Filippo Maria Visconti.

It will be his successor, Francesco Sforza, to order the creation of Naviglio Martesana, from Trezzo d'Adda to Cassina de 'pomm.

FROM THE SPANISH DOMINATION TO THE BEGINNING OF 1800

Of the long Spanish domination on the hydrographic map of Milan remains the Darsena, made from 1603 to 1605 with the deviation of the Olona who became its direct tributary, and the displacement of the Conca di Viarenna.

There will be the Austrians at the head of the duchy when Naviglio di Paderno in 1777 and Redefossi was excavated; always under Austrian rule navigation on Naviglio Pavese was inaugurated in 1819.

VILLORESI, "PORTO DI MARE" AND THE COVERAGE OF NAVIGLI

(Naviglio in via Fatebenefratelli)

Villoresi canal was made between 1877 and 1890, when in the city the pond of Santo Stefano was already silted and so several irrigation ditches.

Also worthy of mention, though never built, is Porto di Mare ("sea port"), the infrastructure that would have allowed the survival of the waterway system of Milan; according to a project of the 1917 in the area between Corvetto and the city limits a port to replace docks in Porta Ticinese had to be placed, but the work was never completed.

Of this project remains today only the name of the homonymous Metro station.

On March 3, 1928 permission was requested to cover the so-called "internal trench", namely the section of Naviglio from Piazza San Marco to Porta Genova, motivated by new roadway and hygienic needs. The coverage of the the Navigli took place between 1929 and 1930, creating a ring of streets that took its place and was called Cerchia dei Navigli, which became the inner ring road of Milan, although even then was called "noose around the neck" rather than "ring" because of its short range, carrying vehicle traffic in the city center.

(Naviglio coverage in Via Senato)

ROGGIA VETTABBIA

Roggia Vettabbia, as mentioned above, is a watercourse traditionally very important for its contribution of irrigation water to the agricultural area south of Milan and is also one which has the highest contribution of urban sewage.

It stems originally from the pit inside Navigli, in Via Molino delle Armi.

Now it receives water from the natural channel of San Marco and the Seveso in addition to waste water (purified) of the municipal sewer.

It flows covered until Via Carlo Bazzi, and at via Castelbarco receives the largest sewer called Gentilino, which serves much of the historic city center.

Later, after Via Ripamonti, before reaching viale Ortles, it receives the collector Vigentino, which also serves the historical center.

Downstream of this input there are the first irrigation ditches of some importance, and finally it reaches the area of Nosedo thus giving rise to other ditches and also receiving the contribution of Nosedo ditch, the main collector of the sewerage network in Milan, and two other minor collectors, from via Ripamonti, via San Dionigi and via Sant'Arialdo.

Then it feeds with various branches a vast agricultural area of about 3700 hectares and finally flows into the Lambro, north of Melegnano.

(Vettabbia "valley")

Deeply changed by the anthropic intervention the river valley, originally carved by the waters of Seveso, is currently still perceptible only to a small extent; although in the recent process of leveling of the soil, in fact, a slight depression still bears witness of its presence.

The existence of Vettabbia, the flumen mediolanensis, was crucial to locate in the twelfth century the abbeys of Chiaravalle Milanese and Viboldone, quickly becoming the real "backbone" of their vast possessions.

The rich heritage of ditches, collectors and drainage systems is certainly due to the complex task of extension and reorganization of the irrigation network performed by monks.

(Roggia Vettabbia in 1880)

EARTHCACHE

In order to register as a "found" this earthcache you must answer the following questions:

1) What kind of aquifer is the one that causes flooding in the Milan subway?

Now go to the coordinates indicated by the listing: under the road, easily visible, there is Roggia Vettabbia.

2) What is the width of the watercourse (in meters)??

3) How the waters of the canal seem to be visually and olfactory? Apparently clear or muddy? Polluted or clean?

4) MANDATORY TASK: take or a selfie or a photo of your GPS/smartphone/nickname (choose one) in foreground at EC location.

Please do not write answers in the log, but send them through my profile on geocaching.com.

You can do the log when you have posted answers, without waiting for my confirmation.

If your answers are wrong I will contact you.