Bed: a layer, sheet, or side of stone that is horizontal

Cleavage: The ability of a rock mass to break along natural surfaces; a surface of natural parting.

Coping: A flat stone used as a cap on a freestanding wall, usually to protect the wall from weather.

Course: A horizontal range of stone units running the length of a wall.

Curbing: Slabs and blocks of stone bordering streets, walks, etc.

Cut Stone: All stone cut or machined to given sizes, dimension or shape.

Dressed or Hand Dressed: The cutting of rough chunks of stone by hand to create a square or rectangular shape. A stone that is sold as ‘dressed stone’ generally refers to stone ready for installation.

Drip: A recess cut under a spill or projecting stone to throw off water, preventing it from running down the face of a wall or other surface, such as windows or doors.

Dry Wall: A stonewall that is constructed one stone upon another, without the use of any mortar.

Face: The exposed portion of a stone.

Lintel: A stone beam or horizontal member spanning the top of an opening, such as a doorway or window, and supporting the wall above it.

Quoins: Stones at the external corner or edge of a wall emphasised by size, projection, rustication, or by a different finish.

Rustication: Recessing the margin or outer edges of cut stone so that when placed together a channel or strongly emphasised recess is formed along each joint. The stone face may be smooth, rough or patterned with its outer edges tooled smooth or bevelled.

Sawed Edge: A clean-cut edge generally achieved by cutting with a diamond blade, gang saw or wire saw.

Sawed Face: A finish obtained from the particular process employed to produce building stone. Varies in texture from smooth to rough and is dependent on the materials used in sawing; characterized as diamond sawn, sand sawn, chat sawn or shot sawn.

Sill: A flat stone used under windows, doors and other masonry openings.

Stone: Sometimes synonymous with rock, but more properly applied to individual blocks, masses, or fragments taken from their original formation for building.

Stone dressing

Some common methods of dressing and cutting stones to get the desired surfaces are:

Scrabbling: the stone is roughly shaped (dressed) using a hammer and chisel.

Hammer dressed: raised portions of the stones are removed and the stone is made regular but remains rough due to hammer marks.

Tooled: chisel marks are deliberate and obvious on the stone face.

Sawn: the stone surfaces show the regular markings made by a saw.

|

|

|

| Scrabbled Sandstone |

ScrabbledGranite |

Sawn Sandstone |

The dressed stone faces may be further subject to different finishing processes to create aesthetic effects.

Stone finishing

Natural Cleft: this finish is associated with materials that are layered and thus, when split, do so on a natural lamination creating what is known as a natural cleft finish. Slates are the most common types of stone that are split naturally.

Split Face: the stone is fractured to give the face a rough natural texture.

Bush-Hammered: a bush hammer is a specialized stone-working hammer with a head that resembles a meat-tenderizing hammer. The result leaves the surface of the stone fairly smooth with small indentations. A bush-hammered finish can be applied to nearly all stones.

Chiselled: produces stones with uniform joints and faces that show the regular indentations caused by the chisel.

|

|

|

| Splitface Granite |

Bush Hammered Sandstone |

Chiselled sandstone |

Honed: this finish is created by slightly buffing the surface. The result is a smooth but dull appearance.

Polished: a polished finish is created when a stone surface reaches its most refined stage. It is buffed to a high shine that gives the stone depth and a rich appearance. It is applied particularly to granites, marble and limestone. Most frequently seen on tombstones.

Types of stone masonry

Masonry can be classified according to the thickness of joints, the continuity of courses and the finish applied to the exposed stone face.

Stone masonry is classified as:

Rubble masonry: walls and buildings made from blocks of undressed or roughly dressed stones in which the adjoining sides are not required to be at right angles. There are typically wide joints between stones.

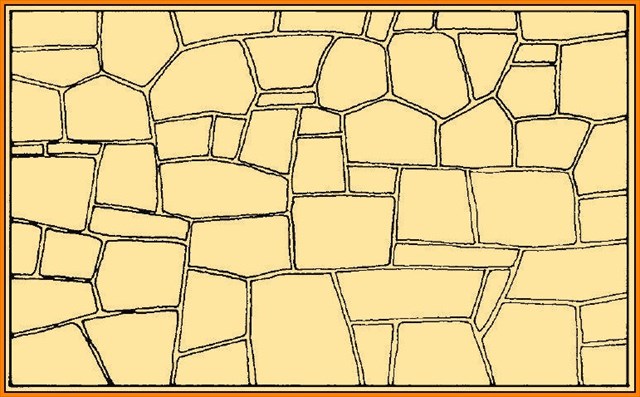

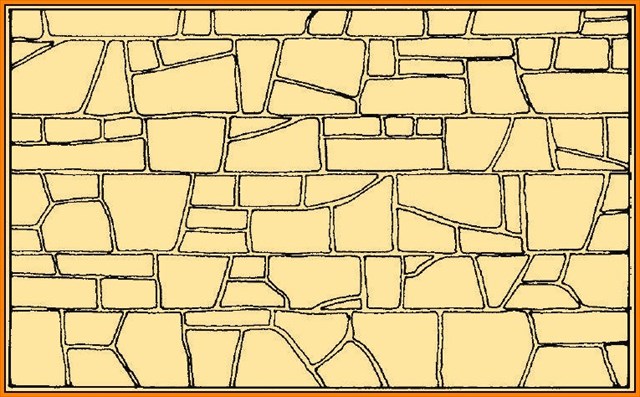

a. Random rubble: utilizes irregular shaped stones

i. Uncoursed: shows no obvious horizontal alignments

ii. Coursed: has clear but irregular horizontal alignments

|

|

| Random Uncoursed |

Random Coursed |

b. Squared rubble: stones have been roughly squared

i. Uncoursed: shows no obvious horizontal alignments

ii. Coursed: has clear but irregular horizontal alignments

iii. Regular coursed: stones are laid in regular courses

Ashlar masonry: building with stones that have been carefully dressed into regular shapes. Stonework that is cut on four sides so that the adjoining sides will be at right angles to each other, is known as ashlar, no matter whether the face is dressed or not. Ashlar is characterized by narrow joints between adjacent stones. When stones are cut to form thin “tiles” that are used to disguise underlying brick-work or concrete, they are termed cladding.

|

|

| Squared Rubble Coursed Granite |

Sandstone Ashlar Cladding |

Cape Town Building Stones

Until the mid 19th century only local peninsular stones were used for building, the Malmesbury hornfels (a fine to medium grained rock formed by thermal metamorphism) and slates (very fine grained metamorphic rock with marked cleavage); light grey porphyrytic granites of the Cape Granite Suite; and quartizitic sandstone from the Table Mountain Group. During the 1870s and 80s limestone from England and granite from Scotland were brought to Cape Town for some prestigious buildings (Learn more from Earth cache GC610YF). From 1890 a medium grained grey granite of the Cape Suite, called“Paarl Grey” as it was (and still is) quarried near Paarl, became popular in Cape Town. With the opening of the railway to Johannesburg, sandstones from the Free State and granites from the Transvaal were railed to Cape Town.

The original church buildings at St. Pauls’ and St. Thomas’ were of random rubble construction and mainly uncoursed. The 20th century extensions are mainly coursed squared rubble, with some ashlar, and with quoins that have sawn or bush-hammered finishes. Granite steps, lintels and sills occur. Foundation courses are occasionally of Malmesbury rubble.

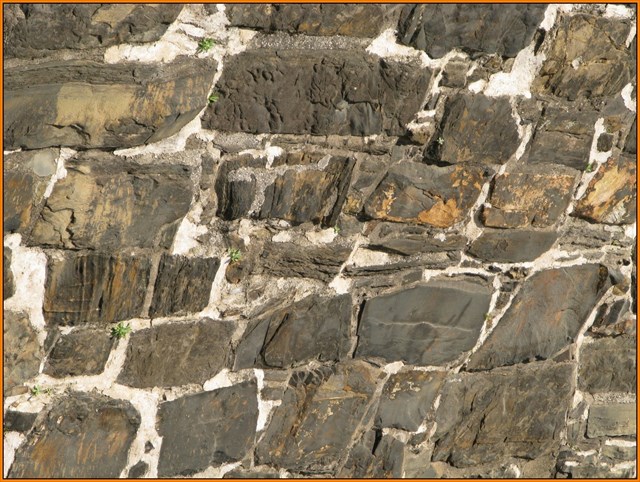

The Malmesbury Hornfels and Slates

as building stones

This group of rocks were the first to be used in Cape Town buildings. The Castle of Good Hope is almost completely built of roughly dressed dark grey hornfels and slates obtained from quarries at the base of Signal Hill. Although a durable and hard building stone it is difficult and time consuming to dress, making it uneconomical for coursed and ashlar building. The hornfels is consequentially used mainly for foundation stone, for random rubble garden walls, and as concrete aggregate. The slates mainly for dressed, natural cleft finished paving slabs as they separate readily along cleavage planes.

Malmesbury Hornfels: Random Rubble

The Peninsula Formation Sandstone

as a building stone

The Peninsula Formation consists of uniformly light-grey, medium- to coarse-grained, well-bedded quartzitic sandstone. It consists mainly of quartz grains, with a small percentage of feldspar, set in a clay matrix. Cross-bedding is common in this thick-bedded formation. The thick bedding allows the formation to be quarried in large blocks suitable for dressing and finishing. Rocks with this characteristic are referred to as "dimension stone". The large blocks are sawn into building stones of fixed dimensions. (Paving stone, such as Malmesbury slate, differs from dimension stone in that it can only be produced in relatively thin slabs of uniform thickness, and not in blocks.)

In Cape Town buildings one face of the Peninsula sandstone is often not sawed but is either hammer dressed, to give a natural look to the exposed face, or bush-hammered or chiselled to add texture to the stone face. The latter finishes are often seen on quoins in squared rubble and in ashlar masonry that uses Peninsula Formation sandstone.

|

|

Peninsula Sandstone:

Coursed Random Rubble |

Peninsula Sandstone:

Coursed Squared Rubble |

The Cape Granites

as building stones

Granite has been used extensively in Cape Town for buildings, curb stones, tombstones and monuments. Granite is composed mostly of two minerals: quartz and orthoclase feldspar (a potassium-rich variety of feldspar). Quartz must make up at least 20% of the rock and orthoclase at least 35%. If either of those criteria is not met, then the rock is not strictly granite. The remaining rock (up to 45%) can be one or more other minerals, such as plagioclase feldspar (a sodium-rich variety), hornblende, pyroxene, muscovite, or biotite (the last two are kinds of mica). (Learn more from Earth cache GC1YZN0).

There are two obvious physical properties of granite that determine what it looks like: its texture (the size of the individual mineral grains) and its colour. The variability in these two properties leads to a wide range of the appearance of granite. Variations in the feldspars are responsible for most of the textural and colour variations in granite. White feldspar, (a pure sodium feldspar), gives a very pale grey colour to granite. Most mixed sodium/potassium feldspars tend to have pastel shades. The percentage of heavy mafic (magnesium and iron) minerals determines how dark the granite becomes. The different size and colours of the grains of different minerals impart the characteristic 'speckled' look to granite. All granite has individual mineral grains that are visible to the naked eye. Under certain conditions the mineral grains can grow very large. When that happens, the granite is called a pegmatite.

Although granite is the most common rock in the earth's crust very little of it can be used for building stone. Only granite that is free from cracks and unaffected by weathering can be used. Unweathered granite can be quarried in large blocks because of the inherent texture developed in the granite as the feldspar crystals align themselves during the intrusion and cooling of the magma. Once the grain in the granite has been determined, and the exfoliation crack system and other zones of weakness noted, the process of breaking out individual large blocks of dimension stone is facilitated. Long before diamond-tipped tools were available quarrymen used the grain of the granite to help them split the rock along predetermined planes using very simple hand tools, wedges and hammers.

The granites from the peninsula used for building are usually of very light grey colour, coarse grained and porphyritic. On occasion peninsula granites may have beige to light brown colour due to staining from percolating iron-rich waters. They are mainly hammer dressed for squared rubble building, sometimes sawn for squared coursed, and nearly always sawn for ashlar.

|

|

| Granite: Squared Rubble |

Granite Ashlar |

.

Sources Used

D.I. Cole, The Building Stones of Cape Town, Council for Geoscience, Popular Geoscience Series 3, 2002.

C. James, Cyclopedia Of Architecture, Carpentry And Building, 2007

J.N. Theron et al, The Geology of the Cape Town Area, Geological Survey, 1992.

Jane Whaley, The Cape Peninsula, Geo Tourism Africa, Vol. 7, No. 1 – 2010. http://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2010/01/the-cape-peninsula

http://www.stonesurfaces.ca

http://www.cliftgranite.co.za

www.buildingstoneinstitute.org/technical-stone-information/rock.../glossary-of-terms/