Submit your answers by E-Mail before logging your find.

Logs submitted without emailing an answer will be Deleted.

If you are doing this earth cache as a group, each person logging a find must submit their own answers to each earth cache question.

1. Locate the contact line between the two formations. Describe what you see on each side of this line.

2. Estimate the heights of both formations, on either side of the contact line.

3. Estimate the height of one of the small caves that are still forming.

4. Estimate the angle of the layers as they dip back along the cliff.

5. Search the cobbles on the beach. Find some that show the distinct markings from the Manicouagan impact.

6. Post a picture in your log with a personal item or hand in picture to prove you were there.

[REQUIRED] In accordance with the updated guidelines from Geocaching Headquarters published in June 2019, photos are now an acceptable logging requirement and WILL BE REQUIRED TO LOG THIS CACHE. Please provide a photo of yourself or a personal item in the picture to prove you visited the site.

This earthcache is best viewed at low tide. Check the tide times here - https://www.tideschart.com/Canada/New-Brunswick/Saint-John-County/St_-Martins/

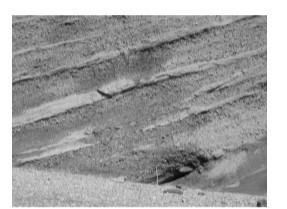

At the posted coordinates, the cliff and sea caves that you see to the east were formed in the Permian/Triassic age and the rocks are estimated to be 201 to 252 million years old. They belong to the Honeycomb Point, Quaco and Echo Cove Formations.

It is easy to see where the coarse boulder conglomerate of the Quaco Formation contacts the Honeycomb Point formation.

The nearby sea caves are found in the Triassic Honeycomb Point Formation sandstone. These rocks are about 250 million years old. They are overlaid in the middle of the cliff face by the bouldery conglomerate of the Quaco Formation. Both these sediments were laid down on rivers and alluvial fans in a rift valley that was part of the opening of the Atlantic Ocean when the tectonic plates separated.

Sedimentary layers within the conglomerates consist of horizontal sandstone layers, which have a maximum estimated thickness of 2-3 meters. Rain, ice and tidal action wore away between the horizontal sandstone layers, causing fractures that sometimes extended deep into the cliffs. As the sandstone layers on top of the fractures were left unsupported, chunks collapsed, creating small caves that grow larger over time. The floors of the caves follow these fracture lines.

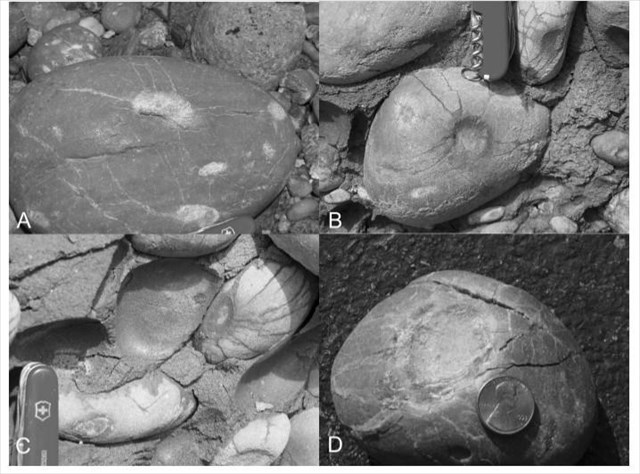

The Quaco Formation at this location consists of well rounded cobbles or rock fragments of varied composition that are larger at the base and become mixed in size toward the top of the cliff. This is accompanied by a corresponding decrease in average cobble size from approximately 12 centimeters. at the bottom to 2 centimeters. at the top.

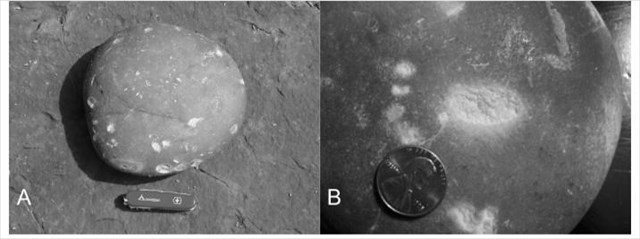

Figure 1.

The most distinctive cobble type of the Quaco Formation is a banded quartzite that, because of its hard composition, generally displays crescent percussion marks and pits. Although the source of the quartzite is not known, the same material is found in the Precambrian and Carboniferous geology of southern New Brunswick. The greater degree of rounding of the cobbles and the progressive mixing up of quartzite with less well rounded cobbles of local material suggest that the quartzite was moved from a source that was some distance away to the south or southwest. Sedimentary layers within the conglomerates consist of horizontal layers, which have a maximum estimated thickness of 2-3 meters.

The most distinctive feature of the Upper Triassic Quaco Formation is the occurrence of centimeter size circular to elliptical markings, and indentations on the cobble surfaces. Also present on many of the cobbles are fractures that radiate from these indentations. The smooth-surfaced depressions that occur on cobbles from other locations originate from tectonic pressure and compression. However, the radial fracturing of the cobbles, grain fracturing within the cobbles, and the spalling or breaking off of cobbles could be explained as the result of concussion fracturing at points where cobble collisions occured during the passage of strong shock waves. The open nature of some of the fractures and small fault lines of the cobbles suggest that tectonic pressure here only enhanced previously formed concussion fractures.

Figure 2.

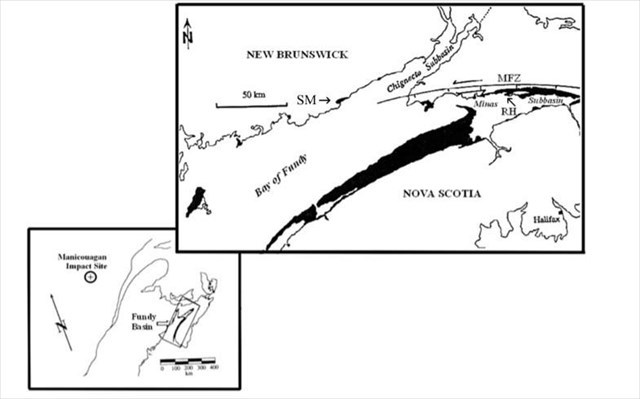

The Manicouagan Crater is one of the oldest known impact craters. It is in the Côte-Nord region of Québec, Canada. It was caused by the impact of a 5 kilometer diameter asteroid about 215.5 million years ago,in the Upper Triassic period. The ~100 kilometer wide Manicouagan meteor impact structure is one of the largest and well-documented impact sites. It was once considered a candidate for the cause of end-of-Triassic life extinctions. This raises the intriguing possibility that the seismic energy of the Manicouagan impact was sufficient to cause rapid collisions between the cobbles of the Quaco Formation in the Fundy Basin. The Manicouagan structure is the closest recognized impact structure that occured after the laying down of the Quaco Formation.

The Manicouagan impact released energy equivalent to nearly 108 Megatons, which generated major seismic events over a wide area. Assuming 108 Megatons of impact energy, this is equivalent to an earthquake of magnitude 9+. The amplitude of vertical ground displacement generated by this impact was greater than 10 meters within 100 kilometers of the impact site, and nearly 5 meters at a distance of 700 kilometers.

An event of this magnitude is forcast to occur every 250,000 years.

Figure 3.

Virtually all of the cobbles in the conglomerate, that are still in contact with surrounding cobbles, contain these concussion markings. They are absent on cobbles supported entirely by the sandstone matrix. The markings are nearly circular to elliptical in outline and 2 millimeters. to 25 millimeters wide. Most markings have an indentation up to 5 millimeters deep, although many markings display no measurable depression of the cobble surface. On the quartzite cobbles, the marks and identations are nearly white, contrasting with the reddishbrown coating on other cobbles. They are commonly surrounded by a 2 to 10 millimeters. wide ring that comprises a zone of closely-spaced (under a millimeter) small fractures.

Figure 4.