This is an Earthcache – as such, there is no physical cache. Instead you will partake in a geology lesson by making observations and answering 6 questions about the island.

Hart-Miller Island State Park can only be reached by a personal boat and is open from 8 a.m. till sunset (Only Registered Campers can be on the island after sunset) from May 1st - September 30th. The North End of the island is still a construction site and is off limits.

The closest public kayak launch point is at Rocky Point Beach and Park, which has entrance fees. You can visit this LINK to see this parks hours of operation and list of fees. It is approximately a two mile long paddle to Hart-Miller Island from Rocky Point State Park. The route is across open water with strong currents, no shelter from wind, and heavy boat traffic.

The Maryland Environmental Service offers boat shuttled field trips to the island for small organized groups. You can visit this LINK to find information on booking. These field trips are FREE and are usually 2 - 3 hours in length. NOTE: Field Trips were temporarily suspended during the COVID19 pandemic, but may resume with restrictions.

HART AND MILLER ISLANDS

Originally Hart, Miller, and Pleasure Islands where all part of a one large peninsula that extended from Edgemere, Maryland. Hart and Miller Islands (both named after their 19th century landowners) had shrunken down to less than two times their size in a century. An 1846 map has Hart Island listed as being 263 acres and Miller Island as being 124 acres. But by 1967 the Baltimore Sun described the “thickly wooded” Hart Island as being only 120 acres, and the “bald” Miller Island was listed as being 40 acres.

The Hart-Miller Island that exists today started to take its current shape more than 50 years ago as a solution to the problem of where to place the tons of sediment dredged from shipping channels. The shipping channels were dredged to a depth of 50’ and maintenance dredging is performed each year so that cargo can continue to reach the Port of Baltimore. The solution became to deposit and contain the sediment here atop the remains of these two natural islands.

WHY DOES MARYLAND DREDGE?

Open shipping channels are as important to ports as lanes are to highways and runways are to airports. The Port of Baltimore is one of America's busiest deep-water ports and was the third-largest handler of containerized cargo on the Eastern seaboard. Approximately 15,330 of the jobs in Maryland are generated by the port activity here, and approximately 140,000other jobs in the state are directly related to activities at the Port. The Port of Baltimore generates approximately $3.3 billion annually for the local business, workers, the city, and state.

In 1996, 400 million cubic yards of material was dredged from the nation's waterways. The channels serving the Port of Baltimore extend from the Patapsco River, 150 nautical miles through the Chesapeake Bay to the Atlantic Ocean. Vessels arrive at and depart from the Port of Baltimore via the southern Chesapeake Bay (Cape Henry) route or the northern Chesapeake Bay route through the C&D Canal. To compete with other coastal ports with closer access to the Atlantic Ocean, and to be able to service large vessels, the Port of Baltimore must have a sailing draft of 33 feet or less. This means that Maryland’s shipping channels must maintain channel depth of 50 feet.

HART-MILLER ISLAND

When it was announced that there would be a deepening of the harbor channel from 42 feet to 50 feet, it became apparent that a safe and economic way would be needed to place the 52 million cubic yards of dredged sediment created from the project. In the past, disposal of dredged material would be placed in other areas of the Chesapeake Bay, but there was great concern that those practices would create severe and irreversible impacts on the marine ecosystem. On the other hand, disposal on land often incurs high costs, and that comes without a guarantee that there would be no harmful contamination. It became more desirable to reuse the material in some way, and this is where Hart and Miller Islands comes in.

In 1972 Maryland developed a plan to build a 4-square mile “potato shaped” artificial island in the bay with an 18-foot retaining wall covered with rip-rap. This dike would be created of permeable sand that would allow water to flow through without releasing the contaminants. Construction of the dike would take two years, with a filling and settling to require a 20 to 30 year period. When the dike was completed, its walls would stand eighteen feet above mean low water, much higher than the maximum elevations of the Hart and Miller Islands in 1978, which were 5.5 feet and 2.3 feet, respectively.

In 1978 residents and environmental groups filed a lawsuit to stop the project, bringing construction to a halt. This litigation also stopped the deepening project in the shipping channel because there was nowhere to place the material. In 1979, with the future of the port in jeopardy, it was Maryland Governor Harry Hughes who said, “The Port of Baltimore is in a Dredge or Die situation.” The lawsuit ended in 1980 with the Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Port, and although the citizens were unsuccessful in stopping the formation of the dredge island, the litigation caused a 5-year project delay and added millions of dollars of cost to complete the work. The Supreme Court decision also constituted the creation of a citizens oversight committee to oversee the development of the project site.

The actual construction of the dike started in 1981. The Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Port Administration turned the two islands into one by building a perimeter of dikes that encompassed much of the islands' original footprints. This created a huge storage bin or containment cells capable of holding several decades of dredged-up sediment. Completed in 1983, this engineered island received its first loads of sediment in 1984. When it received its last load of dredge in 2009 the island had grown to be 1,100 acres.

WHAT IS IN BALTIMORE'S DREDGE?

The harbor floor predominantly consists of silky dirt, or silt, that gets swept around with the currents. During the original deepening of the channel, this mud also contained compounds such as PCBs and hexavalent chromium. Many of these old contaminants are left over from the days when the city's industrial manufacturers used the harbor water to flush away chemicals, unwanted waste, and heavy metals.

When dredged material was scooped up and barged over to Hart-Miller Island, it was meticulously checked to make sure it stayed in safe standards. As the soupy material arrived, it was mixed with water and pumped from barges into the basin that makes up the interior of this island.

After the sediment settled at the bottom of the basin, the water on top would be pumped out leaving the dredged material behind. All the while the quality of the water that was being pumped out into the bay was monitored and tested, proving that contaminants stayed tightly bonded to the sediment left behind. Lab technicians kept watch for a "chemical soup of deadly pollutants" that including heavy metals, ammonia, PCB’s, selenium, barium, mercury, and cyanide. These tests also included the degreeless of acid or baseness of the discharge or pH. Although contaminants common to the Bay are present, material that is hazardous to human health are not permitted to be placed in dredged material containment facilities in Maryland. The contaminated top layer soils from the harbor bottom where first to go into the basin, with the clean deeper layers and continued maintenance material from the harbor being added on top later in the project. This clean layer is now the dirt that you are standing today.

Plenty of World War II ordinance was dug up during dredging operations, including over one hundred corroded hand grenades. A human skull was discovered when it was blocking a pipe emptying sediment into the containment area, it was removed and turned over to the police.

DREDGED SPOIL to SOIL

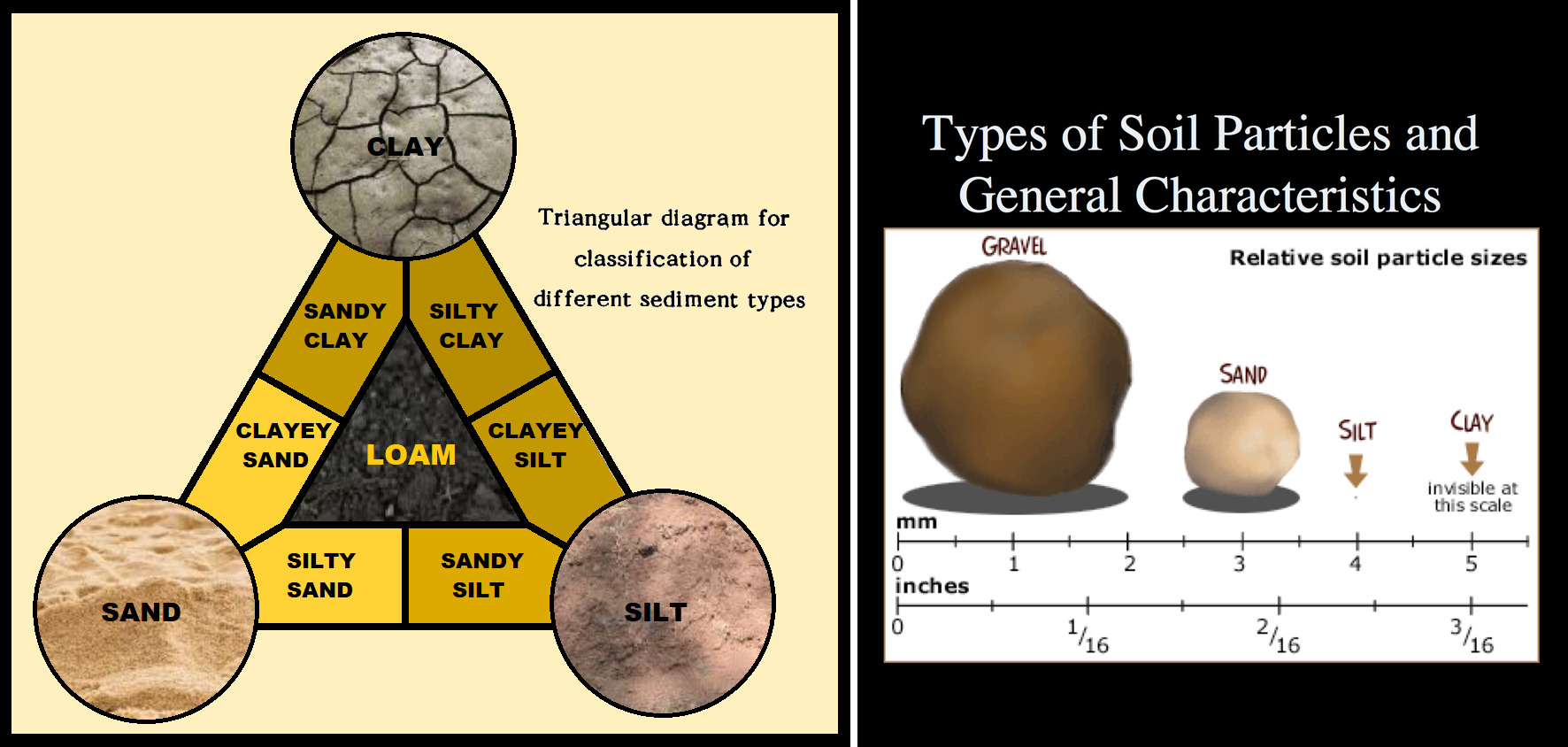

Grain size classification defines soils as boulders and cobbles, gravels, sands, silts, clays and peats, and organic soils. Soils always consist of different grain sizes. Particle size distribution is used to quantify the relative composition of the soil and define the grain size which is a useful indication of the soil type. Sands, gravels, and silts are the most commonly encountered soils in dredging projects.

SAND is an incoherent soil. This means there are no bindings or forces of attraction between the grains, nor are there any forces of attraction between the grains and the water. This makes sands relatively easy to dredge. Sand grains range from 0.06mm to 2mm and all particles are visible to the naked eye. The soil is not compressible and has very little cohesion when dry.

SILT is a sediment material with an intermediate size between sand and clay. Carried by water during flood it forms a fertile deposit on valleys floor. The particle size of silt ranges from 0.002 and 0.06 mm. Due to its fineness, when wet it becomes a smooth mud that you can form easily into balls or other shapes in your hand and when silt soil is very wet, it blends seamlessly with water to form fine, runny puddles of mud.

CLAY is a soil consisting of particles smaller than 0.002mm. Clay exhibits strong cohesion and plasticity, making it nearly impossible to dredge just by means of suction. Clay is a fine-grained cohesive soil that sticks together readily and form a sticky or gluey texture when they are wet or dry. Clay soils hold a high amount of water due the spaces found between clay particles.

LOAM is a mixture of clay, sand and silt and benefits from the qualities of these 3 different textures, favoring water retention, and air circulation. These soils are fertile, easy to work with, and provide good drainage.

HABITAT CREATION

As the dredged material was placed in the south cell, mudflats formed, but as the dredge dried the habit land was dominated by Phragmites. In 2002 restoration of the land was started with three open water habitats targeted for creation:

*Mudflats are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers

*Grasslands are areas where the vegetation is dominated by grasses. Grasslands occur naturally on all continents except Antarctica and are found in most ecoregions of the Earth.

*Habitat for sand/shell nesting species.

One of the first steps for creating these habitats was to control the invasive Phragmites by mowing and spraying. The second step was to design a water supply to keep the mudflats wet and flooded. This flooding also helped control the Phragmites. During migration seasons the water level is slowly drawn down to expose the invertebrates in the mudflats for the birds. A nesting island was created in the mudflat. An uplands/grasslands area was created for migratory birds.

IN CONCLUSION

The result of all the engineering was to demonstrate a beneficial way to use dredged materials by saving two islands, providing a habitat for wildlife, and a park and beach for use by the public.

LOGGING REQUIREMENTS:

To log this Earthcache: Read the geology lesson above. Answer all six questions posted below. Answers can be sent via e-mail or messenger contacts on my Geocaching profile within a reasonable time. Group answers are fine, but do not post the answers to the questions in your logs. After a polite warning I will delete logs of those who fail to meet the geological logging requirements.

QUESTION 1. Why did the state of Maryland save Hart-Miller Island from eroding away?

QUESTION 2. At the posted coordinates, looking north, the west side of the road is the original island, while the east side is the newer dredged material. From your observations, how do the newer dredged landscape features differ from that of the original island?

QUESTION 3. Standing at the second waypoint, reach down and grab some soil and then use the soil texture protocol chart to determine the classification of soil here. What classification of soil do you believe this is?

QUESTION 4. Now that you have classified the soil, would you say that this soil is permeable, or do you see signs of runoff?

QUESTION 5. Standing on the trail at waypoint two, what remnants of the engineering project can you see near here?

QUESTION 6. The original Hart and Miller Islands eroded to almost nothing in a century. Do you think this engineered island will stand the test of time and avoid eroding away?

POST PHOTO IN YOUR LOG: Posting a photo in your log readily indicates that you (and anyone else logging the find) are at the location. You do not have to show your face, but the photo should be personalized by you or a personal item on Hart-Miller Island. NOTE: Per newly published Earthcache guidelines, this requirement is REQUIRED to claim the find.

Awesnap has earned GSA's highest level:

Awesnap has earned GSA's highest level:

REFERENCES

1. County Islands Studied for Recreational Use John Sherwood, The Evening Sun, January 3, 1962, Page 1M, newspapers.com

2. Hart-Miller Island Increases Public Access Dan Baldwin, The Dundalk Eagle, June 16, 2016, Page 12, newspapers.com

3. Pollutant levels from dredging port are lower than expected Jon Morgan, The Evening Sun, September 25, 1987, Page A1, newspapers.com

4. CLOSURE CONCEPTS FOR HART-MILLER ISLAND DREDGED MATERIAL CONTAINMENT FACILITY Francingues, Vann, Huntley, and Hamons, westerndredging.org

5. Pre-Conference Tour Hart-Miller Island Fanning, Demas, King, Rabenhorst, & Cornwell, 8th International Acid Sulfate Soils Conference College Park, Maryland, USA , July 17, 2016, static1.squarespace.com