The cache is not at the published coordinates.

Historians often miss inventor’s most important inventions — and even miss great inventors altogether! This was never truer than with Charles Steinmetz. But Eli Whitney and Fibonacci definitely prove my point about historians.

Ask any school child what Whitney’s most notable invention was and they will say the cotton gin when, in fact, he was the father of interchangeable parts — the basis of all modern manufacturing. During the Revolutionary War, the government required a large number of muskets. Hand-fitting and filing each piece in the firing mechanism and trigger would have been a daunting task. Therefore, necessity was the mother of invention and Whitney came up with the new idea of identical, totally interchangeable parts.

Fibonacci invented the mathematical series, for which most know him, but he was the son of a diplomat to Baghdad — a center of learning at the time. He brought Arabic numerals back to early Europe, which the world universally uses today. Previously, Europe used awkward and cumbersome Roman numerals. Very few people know this or credit him with that, just like Whitney’s monumentally important interchangeable parts concept.

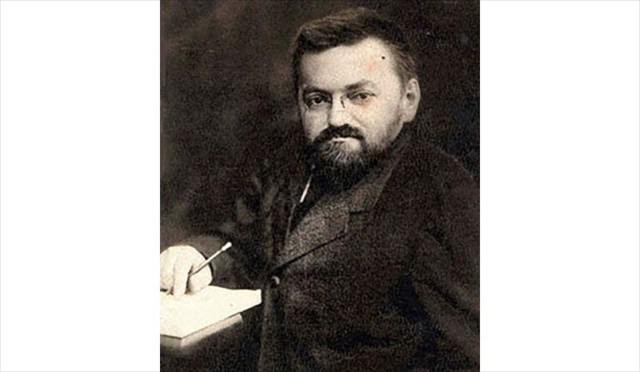

THE FATHER OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING

Steinmetz was born Carl August Rudolph Steinmetz in Breslau, Prussia on April 9, 1865. Steinmetz was a hunchback dwarf only four foot three who also suffered hip dysphasia. These hereditary problems perpetuated themselves through three generations of males in his family. This prompted Steinmetz to never marry and have his own children.

A FORTUITOUS INCIDENT

This, along with several influential newspaper articles that he wrote on this subject, forced him to flee to Zürich in 1888. Soon this same behavior pattern prompted him to leave Zürich and to emigrate to America. Steinmetz was almost turned away at Ellis Island. This was because he was a dwarf, and immigration officers considered Steinmetz medically unfit and asked what profession he had to which he answered “theoretical physicist” to the astonished bewildered official. Then, he presented some of his drawings and said “draftsman,” satisfying the official.

A REAL SELF-STARTER

Steinmetz quickly went to work for Rudolf Eickemeyer in Yonkers, NY in a firm making transformers. Almost simultaneously the newly formed General Electric Company tried to hire him. But he remained loyal and grateful to his first employer, until 1893 when GE bought Eickemeyer’s company, along with all of the patents and designs. That same year, Steinmetz made one of the greatest contributions to the field of electrical engineering. He gave a lecture describing the mathematics of the alternating current phenomena. Previously, this was more of an art than a science by those who called themselves electrical engineers. This breakthrough allowed engineers to design electric motors by mathematics rather than by empirical observations and mere trial and error.

This clear presentation of previously muddled, poorly defined and explained mathematical concepts finally simplified AC where all engineers could both understand and use it. It was Steinmetz who first explained impedances by using complex and imaginary numbers, and this is why many call Steinmetz the Father of Electrical Engineering. This work opened the way to the transmission of electric power in useful quantities over long distances.

SOLVING AC MOTOR INTERNAL HEAT BUILD-UP

In the same year, Steinmetz’s experiments and papers on magnetic hysteresis (the tendency of a material to resist being magnetized or demagnetized) came to the attention of General Electric. This had a profound implication for its day. It reduced the internal heat build-up in electric motors that had previously greatly shortened their useful lives.

This solution of internal AC motor overheating was somewhat of an accident, like many scientific discoveries tend to be. When Mr. Otis of Otis elevator fame needed a more powerful motor to reach higher floors, Steinmetz designed the motor. With each success, Steinmetz’s fame spread. An example was the nephew of Cyrus Field of Atlantic Cable Car Company approaching Steinmetz’s employer Eickenmeyer. He wanted to propel trolley cars by AC.

The problem was that during the transition from DC to AC, the delay overheated motors due to phase problems. Steinmetz mathematically solved this. His solution became the “Law of Hysteresis” also later known as “Steinmetz’s Law.” Steinmetz explained this Law of Hysteresis in 1891 within The Electrical Engineer magazine. In early 1892, he presented this explanation again in a speech to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in New York City. By now, GE wanted to hire Steinmetz even more and the only way was to buy Eickenmeyer’s company — much like Bill Gates did with rival companies last decade and continues to do to a lesser extent today.

AN EARLY DEATH

Steinmetz died of heart failure on Oct. 26, 1923. By that time, he had amassed over 200 patents. When he died, Henry Ford bought the camp where Steinmetz spent his summers frolicking with friends and especially children. He moved it to The Dearborn Institute in Michigan.

Mr. Steinmetz bestowed upon himself a middle name. What is it?

You can validate your puzzle solution with

certitude.