Logging Requirements:

- Describe the color, texture, and grain size of the stone. Did the stone form deep underground or close to the surface? Explain.

- Based on your observations, how would you classify the stone? How does this help us understand the conditions under which the stone was formed? Explain.

- Upload a photo with either yourself or a personal object at the Goddess Diana Fountain.

Installed in 1950, the Diana Fountain in Green Park was part of a postwar effort to bring life back to London’s open spaces. The bronze figure, crafted by Estcourt J. Clack, shows the Roman goddess Diana—protector of the wild, goddess of the hunt—poised mid-stride with a hound at her side. It stands on the site of an earlier fountain that dated back to the 18th century, replacing what had been a long-standing feature of the park.

The fountain is constructed from Cornish Granite, which was quarried in Cornwall, UK. Cornish granite was formed during the final stages of the Variscan orogeny, when tectonic forces compressed and deformed the crust across what is now southwest England. This pressure caused pockets of magma (molten rock) to rise from deep within the Earth, slowly collecting and cooling beneath the surface. As the magma solidified, it created a massive underground body of granite known as a batholith. Over time, the layers of rock above it were worn away by erosion, gradually exposing the granite that had formed far below the surface.

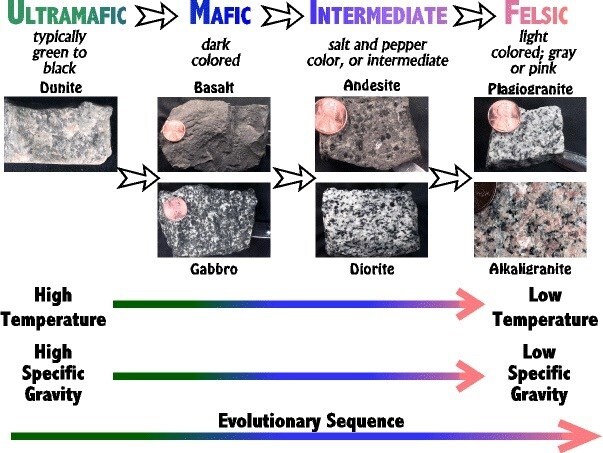

Mafic and felsic are often used to describe the chemical composition of igneous rocks, focusing on their silica content and the dominant minerals they contain. Felsic rocks are rich in silica and usually contain minerals like quartz (colorless or translucent with a glassy appearance), potassium feldspar (often pink, salmon, or white, with a blocky, crystalline texture), and muscovite (silvery, thin, and flaky). In contrast, mafic rocks have lower silica and are dominated by iron and magnesium rich minerals such as pyroxene (dark, with a blocky, crystal structure), amphibole (black or dark green, elongated crystals often forming a prismatic shape), and olivine (glass like, green, and typically granular).

The temperature of magma also influences both its composition and specific gravity. Mafic magmas, formed at higher temperatures (around 1,100–1,200°C), are less viscous and crystallize minerals rich in iron and magnesium first. These minerals are denser, giving mafic rocks a higher specific gravity. It is worth mentioning how crystal size is influenced as well by the cooling rate of magma. Larger crystals form when magma cools slowly deep underground, while smaller crystals result from rapid cooling near the surface. On the other hand, felsic magmas, which form at lower temperatures (650–800°C), are more viscous and crystallize lighter minerals like quartz and feldspar, leading to a lower specific gravity. This ties into the evolutionary sequence of magma, where the initial mafic composition can evolve into felsic over time through cooling and fractional crystallization, as the magma becomes enriched in lighter minerals.