To do this cache, stop at the car park, and follow the Wheelchair accessible track to GZ. Be sure to stay on the track as there are unfenced cliffs in the vicinity. It is recommended that you do this cache in fine weather, and carry water, especially in hot weather. Questions 6 and 7 require travelling along another track (signposted Plateau Walk). There are steps on this walk, and at the time of researching, there was a tree across the track at one point. Because of this, I have made questions 6 and 7 optional if your party is mobility impaired. Please include proof of the impairment (e.g. photograph at GZ including the impairment) if you choose not to answer these questions

Because of issues that Oregon and Colorado GPS units have with paperless caching, the questions are placed at the front. Make sure to read the rest of the information though. It may even have some answers.

To log the cache, answer the following questions and post the replies to me via my Geocaching profile page. Some will require research away from the site. Others need information at the site to answer.

1. According to the visitor information signs near the car park (WP1), who brought the first perambulator (pram) to Kanangra and when?

2. Who first recognised an unconformity? When and where?

3. What did that recognition mean to him in terms of the age of the Earth?

4. Arthur Holmes, who supplied some of the information used here, pushed the age of the Earth back even further. How far, and what technique did he use to measure it? What is the current scientifically accepted age for the Earth?

5. While it is an excellent representation of the geography of the Walls, the information sign near GZ is not very accurate from a geological point of view. What would you do to improve it?

6. Near WP2, there is a significant change in the type of rock. Describe the change. What do you think may have caused it?

7. Near the end of the Dance Cave (WP3) is a very large “boulder” that has fallen. Just beside that rock is a shelf that exposes some tilted rock. Immediately above it are more or less horizontal layers. Are we looking at the unconformity here? Why or why not? What evidence would you look for to prove or disprove your theory? NB Remember you are in a National Park. Do not remove any rock samples. You can do so in a hypothetical sense though if your answer requires it.

8. Post a photo pf your group at or near GZ. If your party includes a member in a wheelchair, you do not need to do questions 6 and 7 as these need a higher level of mobility to answer them.

Earthcache information:

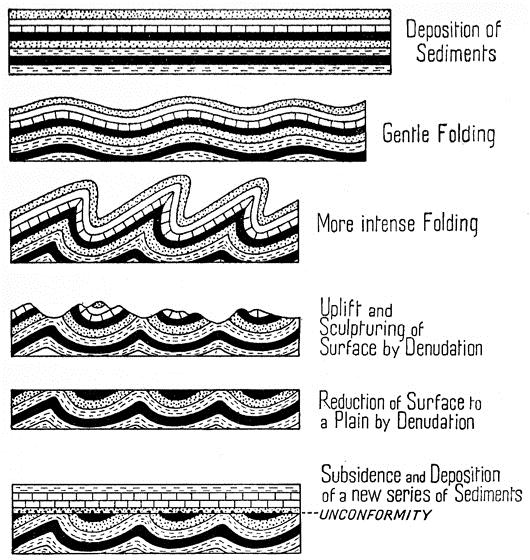

Stratified rocks accumulate layer by layer, and where the beds remain essentially undisturbed, the oldest rocks lie underneath younger rocks above, and the sequence represents an uninterrupted history of the earth at that location. One famous example is the Grand Canyon in the United States. This rarely happens in practice. More often, there is a break in the sequence of deposition, frequently accompanied by a period of erosion, or wearing away of the Earth’s surface. Then a new period of deposition occurs over the old surface. This type of feature is called a stratigraphic break. Stratigraphy is simply the technical word for the layers of rock, so we have a break in the layers. If the break represents a short period of time, it is called a diastem. If, on the other hand, it represents a significant lapse of time, the break is called an unconformity. It is an example of these unconformities that is the subject of this Earth Cache.

There are four types of unconformity that are recognised:

The Angular Unconformity

This is the most obvious kind of unconformity and the first type recognised. The first was identified by James Hutton, frequently called the “father of geology”, during the 1780’s at Siccar Point in Scotland. In this type, first a set of rocks are laid down. These are then tilted and eroded to a level surface. Finally a new set of sediments are laid down and petrified (turned to rock). Because of the enormous amount of time required to first fold the rocks, then erode them to a new surface, clearly an enormous amount of time is lost between the layers directly below and above this type of unconformity.

Paraconformity

If the folding step is omitted from the above, then the resulting structure is called a paraconformity. As these are flat layers deposited on flat layers, these can be extremely hard to detect. Often, the only clue can be an ancient soil layer, or a sudden jump in the age of fossils present. For example, if trilobite fossils are found immediately under a layer containing dinosaur remains, this would indicate a paraconformity.

The Disconformity

A disconformity is similar to a paraconformity in that no folding has taken place, but in this instance, the old surface was not worn completely flat, so there is an ancient series of hills and valleys preserved under flat sediments.

The Nonconformity

In this case, the older, eroded surface is either metamorphic or igneous rock, not showing any distinct layers.

Kanangra Walls

|

|

As you can see in the diagram above, Kanangra Walls exposes an angular unconformity. This unconformity represents the very edge of the large system known as the Sydney Basin. Above the unconformity lie more or less flat rocks of the Sydney Basin. These rocks stretch from here to the coast, south to Kiama. To the north they grade gradually into New England Fold belt somewhere in the vicinity of Scone. The rocks exposed here are the very beginning of the Sydney Basin, dating back to the Permian Era, some 270 Million Years Ago (mya). Immediately below the unconformity, the rocks are of Late Devonian Age, some 400mya. Thus this unconformity represents a gap in the rock record of some 100 million years. In that time, the older sediments were buried, lithified (turned to stone), metamorphosed, tilted and uplifted and finally eroded to the surface that had the Permian and later Triassic sediments deposited on them. These in turn, have been lithified, uplifted and eroded in processes that are continuing today.

References and further reading

Branagan, D. & Packham, G., Field Geology of New South Wales, Science Press Sydney

Holmes, A., Principles of Physical Geology, Thomas Nelson & Sons, London

Pickett, J & Alder, J. Layers of Time: The Blue Mountains and their Geology, NSW Dept of Mineral Resources

Topographic Maps: Kanangra 8930-3-S 1:25000 and Yerranderie 8929 – 4 – N 1:25000

Other EarthCaches exploring aspects of the Sydney Basin

Den Fenella Track looks at how erosion and uplift formed the classic Blue Mountains topography

The Three Sisters EarthCache looks at a famous erosional feature

Katoomba Torbanite - DP/EC51 Permian rocks. One of the economic uses of the rocks of the Sydney Basin

A Lockley Story The ecology of the sandstone plateaux

Lapstone layers One of the major uplift zones showing faults and a monocline

Dundas dig One of the many igneous intrusions into the Sydney Basin that occured in the Triassic. Another economic use.

The Brickpit Earthcache The topmost shale layers in the basin and another economic use.

Hawkesbury Sandstones Triassic Rocks. The most common of the Sydney Basin Rocks. Even though you are at sea level there, the rocks found at the edge of the basin at about 1000m altitude are about 500m under the surface there, giving you some idea of the uplift involved.