Mount Riga State Park

Salisbury, Connecticut

Mt. Riga State Park is one of Connecticut’s undeveloped state

parks. Public access is on CT RT 41 North of Salisbury. The

Undermountain Trail, is the only public trail in the park and is

used to access the Applachian Trail to the west.

The location below is in the parking lot off CT RT 41.

Purpose: This EarthCache is created by the Connecticut

Geological and Natural History Survey of the Department of

Environmental Protection. This is one in a series of EarthCache

sites designed to promote an understanding of the geological and

biological wealth of the State of Connecticut.

Supplies: You will need to bring this write up, a gps

unit a way to take photos and water. Spoilers may be included in

the descriptions or links.

Directions: Public access is on CT RT 41 North of

Salisbury. The Undermountain Trail, is the only public trail in the

park and is used to access the Applachian Trail to the west. The

location below is in the parking lot off CT RT 41.

N. 42o01.728' W. –073o 25.733'

This Earthcache is a strenuous hike in some very pretty woods in

western Connecticut. It is 1.9 miles one-way and involves mostly

uphill hiking on the way in. The highway trailhead has an elevation

of about 750’ above sea level. The junction with the Appalachian

Trail is at an elevation of about 1750’. There is very little ledge

to see. Nonetheless, the geology of the area is interesting

The avid hikers can extend their treck by following the

Appalachian Trail north to the top of Bear Mountain. It is the

highest peak in Connecticut (elevation 2316’) although not the

highest point in Connecticut. The highest point elevation in

Connecticut is on the flank of Mt. Frissell at 2354’. A hike to the

top of Bear Mountain adds about another mile, one-way. The interest

hiker may wish to read a section on Mt. Riga State Park in Joseph

Leary’s book, A Shared Landscape, pp. 203-204 (see reference

below).

Looking at the topographic map, one can see several distinct

regions: the lowland areas to the east, an area of steep slopes,

and, to the west, an upland area on which two mountain peaks

protrude. As you walk up the hill, keep thinking, there is a

geologic reason for this. Unfortunately few rock outcrops are seen

along the trail to verify this assertion.

The lowland areas have an elevation roughly around 700 above sea

level. These areas are underlain by marble and calcium-bearing

gneiss and schist. Geologists refer to this rock formation as

Stockbridge Marble. It was deposited as limestone around

500-million years ago and then was metamorphosed into marble when

the Appalachian Mountains were being formed.

Marble is particularly susceptible to dissolution in acidic

waters. Perhaps you may remember seeing, in an old graveyard,

marble headstones whose lettering has been rendered illegible by

the ravages of weathering. The gravestone weathering was caused by

dissolution in rainwater that is naturally slightly acidic. The

same process has affected natural areas where the bedrock consists

of marble or calcium-bearing schist and gneiss. Over the millennia

rock has dissolved in rainwater or groundwater, creating the

lowlands seen today. We refer to these lowlands as marble valleys.

To the east, the Housatonic River flows in a marble valley over a

good part of its course.

The slopes on the side of the valley, and some of the small

hills within the valley, are underlain gray schist (and locally,

gneiss) of the Walloomsac Schist. The schist is younger than the

marble and overlies it. It is of Ordovician age (~475 million years

ago). The Walloomsac schist is more resistant to erosion than

marble.

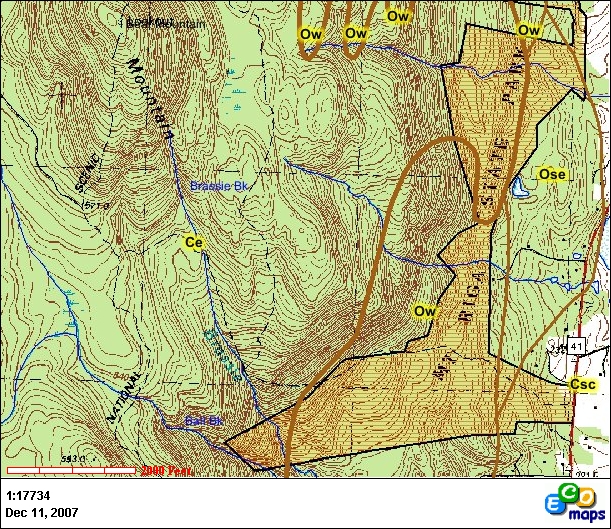

Topographic map (C.I.=20’) of the Mt. Riga area showing

boundaries of bedrock formations. Csc and Ose are the Stockbridge

Marble, Ow is the Walloomsac Schist, and Ce is Everett Schist.

Heavy line separating Everett Schist from other formations is

interpreted to be a fault surface. After Rodgers, 1985.

In some nearby areas, the Walloomsac Schist and the upper part

of the Stockbridge Marble locally contain concentrations of iron

ore minerals. The ore minerals are various iron oxides, including

limonite (Fe(OH)2) and hematite

(Fe2O3). Mining of these ores began during

colonial times and continued until the early part of the

20th century (Pawloski, 2006). Most were mined by

digging a large open pit and hauling the ore over the top and to a

nearby furnace.1 Two old iron mines are noted on the

“Mine-map” of Connecticut (Altamura,

1. The interested cacher may wish to visit the nearby Beckley

Furnace Industrial Park located a few miles to the east.

Information can be found at: Beckley Blast Furnace

htt

p://www.geocaching.com/seek/cache_details.aspx?guid=9256967a-9c84-460a-ac5c-0bf9e162bb76.

1987), one just south of the State Park (Clark Mine; Hobbs,

1907, p.156) and the other near the eastern boundary of the State

Park across from Fisher Pond (Scovill Mine; Hobbs, op.

cit.). Neither was a large enough operation to have resulted in

pits of sufficient size to show-up on current topographic maps

(scars on the topography left from old open-pit mines are readily

apparent in the Lakeville area to the south). Neither sites have

been located.

The highland areas are underlain by an older rock, the Everett

Schist. It is lighter colored than the Walloomsac Schist and

slightly coarser-grained. It formed about 500-million years ago.

The Everett Schist forms outcrops along the almost north-south

mountain escarpment and it underlies all of the uplands above the

scarp. Where the Undermountain Trail crosses the escarpment,

Everett Schist crops out. They are the only outcrops found of this

trail. They are gray somewhat gneissic schist that is highly

contorted and folded (see picture below).

Contorted layers seen in a boulder of the Everett Schist near

base of cliff. View shows about 2 feet of

boulder. |

|

The forming of the Everett Schist and its relation to the

Stockbridge and Walloomsac rock units is an interesting story. Five

hundred million years ago the edge of the North American continent

in western Connecticut (see Rodgers, 1985 and Coleman, 2004). In

southwestern Connecticut the continental margin was located in the

Danbury area and in northwestern Connecticut it was located near

the Barkhamsted reservoirs. Limestone, which later was

metamorphosed to marble, formed on top of the continental shelf.

The distribution of marble is one of the tools geologists use to

interpret where the edge of the continent was. The Everett Schist

was originally formed by deposition of mud on the seaward slopes of

the continental margin, east of the continental shelf edge. The mud

later was metamorphosed into schist. How that schist came to be on

top of the continental margin limestone/marble and to its west is

the interesting part.

The initial pulse of mountain building that would ultimately

lead to the rise of the Appalachian Mountain chain began about 440

million years ago (see Coleman, 2005). At that time plate tectonic

processes caused a small island archipelago (or maybe several) to

“smush” into North America, or perhaps vice versa. As this was

happening, the continental shelf buckled downward and mud, that

eventually would form the Walloomsac schist, was deposited over the

lime. As a result of this collision large slices of the continental

slope sediments sheared off and were thrust up and onto the

continental shelf. The thrusting was possibly aided by

water-saturated Walloomsac-muds acting as a slippery base over

which the slices could slide. Thus, today we see the older Everett

Schist lying on top of the Walloomsac Schist and Stockbridge

Marble. It records the first phase of the building the Appalachian

Mountains, which would last another 200 million years or so.

The latest period of geologic history occurred during the last

Ice Age, a mere 20,000-25,000 years ago, and the meltdown of the

glacial ice, which began about 17,500 years ago in southern

Connecticut but around 15,500 years ago in this area.

The ice was as much as 1.5-2 km thick at the height of the last

ice age. Ice that thick is relatively weak and it flows from areas

where the ice is thicker (north) to areas where the ice is thinner

(south). It extended from northern Canada to as far south as Long

Island. Its maximum extent occurred 22,000 to 20,000 years ago.

After that time global climate warmed and the great glacier began

melting. The climate was warmer to the south (as it is today) and

the glacier was thinner in the south; thus, the southern end of the

glacier melted northward. About 15,500 years ago the ice melted

back (north) far enough that the Mt. Riga area was ice free. Ice

persisted in the valleys a little longer.

As ice flows, it bulldozes the soil and scrapes the rock on

which it rides, causing erosion. It also moves all the debris it

erodes. When riding over hills or mountains, the ice melts slightly

at its base on the uphill side and then refreezes when it crosses

the crest of the hill or mountain. Some of the melt-water seeps

into cracks in the rock and refreezes. This action may cause blocks

of the rock to break off the ledge and then to be carried away in

the base of the glacier. Large blocks of rock, frozen into the base

of the glacier can gouge the underlying rock, causing even more

erosion. All the glacial processes resulted in a smoothing of the

landscape to what we see today.

Activity 1: As you hike along the trail, find you way to the

following location,

N. 42o 01.877' W. -073o 26.379'and

consider the following.

This location is off the trail to the north. Be careful and

watch your footing. A cliff will be visible and near its base you

will find numerous blocks of fallen rock and, immediately at the

foot of the cliff, a talus slope. Observe the blocks that rolled

beyond the talus slope. Some are large and some are not so large.

What is most interesting is that they seem to have rolled, large

and small alike, just so far. One could almost draw a line in the

soil beyond which the rocks are not found. The question is whether

this observation in real or imagined? This site was visited in mid

June and again in late November. To find these sizes grouped

together was not expected. One would expect larger rocks to roll

farther after they are dislodged from the cliff and smaller rocks

to stop closer to the cliff base. This is because the larger blocks

will have greater momentum than the smaller ones. If both large and

small roll the same distance, we need an explanation.

If the observation is valid then there are several questions to

ask and answer. Foremost, when did the rocks fall? If it were after

all the ice melted one would expect heavier rocks to roll farther

than lighter ones. The rocks would not have fallen during the

height of glaciation because ice would have carried them off.

Indeed, during the height of glaciation the cliff was surrounded by

ice and the rocks could not fall. Once cracked from the ledge they

were

All pictures taken in vicinity of GPS location given

above. Left picture taken standing at lower edge of boulders

looking upslope. Dense boulder field upslope abruptly ends where

picture was taken. Middle picture shows mid-slope edge of boulder

field a s hort distance toward the northeast; large boulders end at

a line that could be drawn from left-center of picture going

diagonally across picture in uphill direction. Some small cobbles

persist down slope. The density of the cobble population is normal

for the till in the area. Picture to right shows view looking

toward west. Left third of this view is boulder free; right side,

going uphill, contains abundant boulders.

simply engulfed by ice and carried off. They must have fallen

near the end of the glacial age when ice was thinning. Possibly a

small ice cave developed next to the cliff caused by ice flowing

over the top of the cliff and not reattaching itself to the ground

for a few tens of feet beyond the cliff. Or possibly there was a

crevasse that developed just south of the cliff after ice movement

ceased. The point is that there must have been a mass of ice south

of the cliff that stopped large and small blocks alike and, hence,

a line beyond which falling rock did not roll.

This is an interesting problem because several other locations

in Connecticut where, “downstream” (relative to the flow direction

of the ice) from prominent cliffs there are distinct fields of

boulders that have sharp boundaries beyond which the boulders did

not roll. At the end of this EarthCache you are asked to send your

observations and thoughts on the problem.

Activity 2. Proceed to N. 42o 02.095'

W.-073o 27.280'which should be at the intersection of

the Undermountain Trail with the Appalachian Trail, and take a

picture showing you or your companions next to the sign.

The Appalachian Trail heads north and ascends Bear Mountain

about a mile farther north. Leary (2004) reports a magnificent view

from the top of Bear Mountain.

How do people respond to this EarthCache? See activity 2.

Send picture for credit to the Cache manager along with a copy of

your observations from activity one.

Difficulty: 2

Terrain: 3.5

Type of land: State Park

EarthCache category: Glacial geology and geologic

history.

References:

Altamura, R.J., compiler, 1987, Bedrock Mines and Quarries of

Connecticut, with citation

list and references cited. State Geol. and Nat’l Hist. Surv. of

Connecticut, CT Atlas Series, 1:125,000.

Coleman, M. E., 2005, The Geologic History of Connecticut’s

Bedrock. State Geol. and

Nat’l. Hist. Surv. of Connecticut, Spec Pub. #2, 30p.

Hobbs, W.H., 1907, The iron ores of the Salisbury District of

Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts. Economic Geology v.

2:153-181.

Leary, Joseph, 2004, A Shared Landscape: A Guide and History

of Connecticut’s State Parks and Forests. Friends of CT State

Parks, Inc. 240p. May be purchased at the DEP Store, Hartford

CT.

Palowski, J. A., 2006, Connecticut Mining. Arcadia

Publishing, Charleston, SC, 127p.

Rodgers, John, 1985, Bedrock Geological Map of

Connecticut. State Geological and Natural

History Survey of Connecticut, Nat’l. Resource Atlas Series,

1:125,000

<