The Quarry on Menelaus Road EarthCache

The Quarry on Menelaus Road

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (not chosen)

(not chosen)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

The Quarry on Menelaus Road

HISTORY: OPEN CUT MINING

The abundance in Kentucky of limestone formations close to the

surface where small hills rise presents many sites where horizontal

open cuts, or quarries, may be found. The expense of

transporting large, heavy stone blocks combined with the large

number of potential quarry sites has kept the size of individual

quarries small until relatively recently in our history.

Quarries make up in number what they lack in size. That is

why you can find a number of very small quarries widely scattered

about this locality in Central Kentucky. This quarry is in

the region known as the Knobs. Historically, the exploitation

of mineral deposits from copper to iron ore has for the most part

required underground operations. Yet where conditions are

suitable, and the deposits do not occur too far below the surface,

open pit methods have proved very efficient for local needs.

This was especially true for our area during the time of

settlement, of the quarrying of limestone used for houses, the

field walls of farms, and bridge piers and abutments. An

example of this use is a nearby stone fence made from limestone

blocks -- it is pictured below, and you can find it just 0.2 miles

east of the quarry at N37° 38.960' W084° 18.246'.

Open cut techniques used on the frontier had the advantage of

lowering labor costs, as well as increasing safety, when compared

to underground mining of stone. Among the advantages of open

cut mining are the obviation of tasks such as sinking a shaft,

tunneling, and timbering for support. Nor is there a need for

artificial lighting or ventilation. A large disadvantage is

the removal of waste material, called "overburden," from the quarry

site. Prior to the development of mechanized means of

breaking, loading, and hauling away large amounts of undesired

material from the quarry site, limits were quickly reached as to

how large an open cut operation could grow. Since most local

quarries operated intermittently, even a small quarry would see a

lifetime measured in decades.

Quarry men at work (not at this quarry, though)

This site is an excellent example of the type of quarry used for

local stone production until as late as the late 1800s to early

1900s. The cut has been made into the side of a low hill,

with the quarry's lowest level being even with that of the

surrounding terrain. Typically, it took at least two strong,

brave men to quarry stone. One to hold the drill and turn it,

the other to drive it in with a sledgehammer. Once the holes

were deep enough, wedges were driven in to split the rock.

Then the rough limestone blocks had to be loaded onto a wagon or

sledge and taken to the building site where they would be shaped to

fit. It was dangerous and demanding work. Thankfully,

fences are no longer made from quarried stone or field stone.

Today's civil engineering projects such as bridges use reinforced

concrete which calls for volumes of crushed stone a hand operated

quarry could never hope to meet. Modern commercialization of

stone production has lead to the development of extensive

underground mines for limestone. Today most limestone is

crushed to provide stone for aggregate, agricultural limestone, and

for cement and asphalt. And Kentucky is among the top 10

producers of limestone in the country. Times have changed,

and we are left with these small reminders that may pleasantly

surprise us as we are driving down an old country road. They

are reminders of an age when progress was slowly made using hand

labor, horses, lots of sweat and sometimes blood.

Two works made from limestone are shown

below:

A nearby stone fence

The Great Pyramid

GEOLOGY

Across Kentucky, natural outcrops and man-made excavations have

exposed layers of rock strata. To a geologist, these layers

are like the pages in a book, and each tells a part of the geologic

story of Kentucky. Almost all of the rocks exposed at the

surface of the State are sedimentary rocks. Sedimentary rocks

are layered, and can often be traced across broad distances at the

surface and beneath the surface. Geologists can determine the

relative age of sedimentary rock layers from the fossils they

contain. Similar layers can be grouped into units of strata,

just as pages are combined into chapters in a book.

Kentucky in Geologic Time

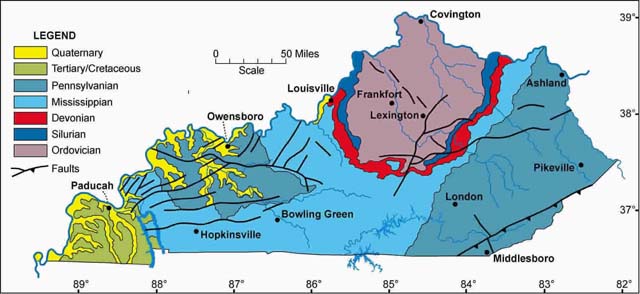

On the geologic map below, each color represents a different age,

or chapter in Kentucky's geologic history. These are very

large groupings of rock strata based on the geologic time

scale.

Although on the map it looks as though each rock unit or chapter

stops where the next begins, older units actually dip beneath

younger units. So on the map above, the Ordovician strata is

exposed in the center of the State, but continues beneath the

surface in the areas where Silurian and Devonian (and younger)

strata occur at the surface. Likewise, Ordovician through

Devonian strata continue beneath the areas where Mississippian

strata occur at the surface, and so on. Each of the periods

colored on the map may contain several hundred to thousands of feet

of rock strata. Geologists divide these larger time-based

units into smaller, mappable rock-based units called groups.

Groups can be divided into smaller units called formations (each

tens to hundreds of feet thick); formations may be divided into

smaller units called members (usually tens of feet thick); and the

smallest units are beds, which usually represent a distinctive

layer of rock.

The Devonian Period

Devonian Strata

On the geologic map of Kentucky, Ordovician and Silurian rocks are

surrounded by a thin ring of Devonian strata (410 to 360 million

years ago). Devonian strata consits of limestones and

dolostones and a thick deposit of dark gray to black shale.

The limestones are mined in the Louisville area. They

sometimes contain abundant fossils, as at the Falls of the Ohio in

Louisville, Kentucky. Thick, dark gray to black shales are

the dominant Devonian strata in many areas of Kentucky. The

color of the shales comes from organic material trapped in the

rock. During the Late Devonian, muds were deposited beneath a

sea that covered most of the eastern United States. Organic

material in the muds was trapped. When the organic-rich

sediments were buried deeper beneath the surface, pressure and

temperature converted some of the organic material in the rock to

liquid form, called oil, and into gaseous form, as natural

gas. The largest gas field in Kentucky, with an estimated

reserve of many billions of cubic feet of gas, is the Big Sandy Gas

Field located in eastern Kentucky. The gas reservoir is in

Devonian shales buried deep beneath the surface. Much of the

oil found in Kentucky was originally in the Devonian shales, but

migrated to other rocks where it is found today.

Devonian Fossils

Devonian rocks are exposed at the surface in the Knobs Region,

which rings the Blue Grass Region. Devonian rocks are absent

in the Blue Grass Region, but occur below the surface in other

areas of Kentucky. During most of the Devonian, Kentucky was

covered by shallow tropical seas, although some very low lands may

have been emergent at times in central Kentucky. During the

later part of the Devonian, deep seas covered Kentucky, and the

water was poorly oxygenated at depth. Dark organic-rich muds

were deposited, producing the Devonian black shales in Kentucky,

which contain oil shales and are a potential source for a variety

of fossil fuels.

All the Devonian rocks found in Kentucky are marine and

consequently all the fossils are marine (sea-dwelling)

invertebrates and vertebrates. Common Devonian fossils found

in Kentucky include sponges (Porifera), corals (Cnidaria),

bryozoans, brachiopods, trilobites, snails (gastropods), clams

(pelecypods), squid-like animals (cephalopods), crinoids

(Echinoderms), and microscopic animals like ostracodes and

conodonts.

Probably the most common sponge fossils found in Kentucky are the

stromatoporoids, or stroms for short. Stroms are calcareous

sponges that form mounds 2 to 3 feet across on the sea floor.

Stroms still exist today in moderately deep water. Devonian

stroms can be seen at the Falls of the Ohio near Louisville.

Fossil bones of giant arthrodires, sharks, and other fish have been

found in the Devonian rocks in the Knobs Region of Kentucky.

Some giant arthrodires, with sharp cutting beaks, grew to more than

20 feet in length and fed on sharks.

The most commonly found plant fossils in the Devonian black shales

of Kentucky are silicified logs (called Callixylon) of the

seed-fern tree, Archaeopteris. Several silicified fossil logs

from these shales in Kentucky are on display at the Smithsonian

Institution in Washington, D.C. Rarely, foliage from these

and other plants is found in these Devonian shales.

The Silurian Period

Silurian Strata

On the geologic map of Kentucky, Ordovician rocks are surrounded by

a ring of Silurian strata (440 to 410 million years ago). The

area where these rocks crop out is known as the Knobs Region.

Silurian strata consists mostly of limestones and dolostones.

Where these rocks dip beneath the surface in the Big Sinking-Irvine

area of eastern Kentucky, they are very porous and form natural

reservoirs for oil. On the geologic map, one can see that the

Silurian rocks do not completely circle the Ordovician strata, but

rather pinch out to the south in Boyle, Casey, Lincoln, and

Montgomery Counties. Where the Silurian rocks are missing,

Devonian rocks lie directly on top of Ordovician rocks. This

is called an unconformity. An unconformity means that a large

segment of geologic time is missing from the rock record, just as

if someone had torn the pages out of a book.

Silurian Fossils

Silurian rocks are exposed at the surface in the Knobs Region,

which rings the Blue Grass Region. Silurian rocks are absent

in the Blue Grass, but occur below the surface in other parts of

Kentucky. During most of the Silurian Kentucky was covered by

shallow tropical seas. However, some very low lands may have

been emergent in central Kentucky at times. All Silurian

rocks found in Kentucky are marine and all the fossils are marine

(sea-dwelling) invertebrates. Common Silurian fossils in

Kentucky include corals (Cnidaria), bryozoans, brachiopods,

trilobites, snails (gastropods), clams (pelecypods), squid-like

animals (cephalopods), crinoids (Echinodermata), and microscopic

animals like ostracodes and conodonts.

DIRECTIONS

From the Kentucky Artisan Center at Berea (exit 77 off of I-75),

proceed east on KY 595. Turn left (east) onto Glades Road

until it intersects US 25 in Berea. Turn left (north) onto US

25 and proceed for 4.4 miles to Menelaus Road. Turn left onto

Menelaus Road and proceed 2.3 miles to the quarry. There is

room to pull off at the side of the road. Please exercise

care with young children. Traffic is light in the area but no

one will expect to find you parked beside the road.

DO NOT LOG AS A FIND UNTIL YOU HAVE A PICTURE READY TO POST.

To get credit for this EC, post a photo of you (I do not accept

pictures of just a hand) at the posted coordinates with the

Menelaus Quarry in the background (like my photo above) and please

answer the following questions.

- How tall is the cut? An estimate is fine.

- Measure the length of the exposed cut, along with the depth

into the hillside. What do you estimate as the volume of

limestone quarried here?

- Do you see any fossils in the exposed beds?

Do not wait for my reply to log your find. I will contact you

if there is a problem. Logs with no photo of the actual

EarthCacher/Geocacher (face must be included) logging the find or

failure to answer questions will result in a log deletion.

Exceptions will be considered if you contact me first (I realize

sometimes we forget our cameras or the batteries die). Logs

with no photos will be deleted without notice. I have used

sources available to me by using google search to get information

for this earth cache. I am by no means a geologist. I

use books, the Internet, and ask questions about geology just like

99.9 percent of the geocachers who create these great Earth

Caches.

Reference: Kentucky Geological Survey at the University of

Kentucky.

Congratulations to

for the

FTF!

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)