Kohler Park Dunes EarthCache

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (not chosen)

(not chosen)

Related Web Page

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

An EarthCache adventure is treasure hunting for the caches that the Earth has stored. EarthCache sites do not use stored containers; their treasure is the lessons people learn about our planet when they visit the site. Visitors to EarthCache sites can see how our planet has been shaped by geological processes, how we manage the resources and how scientists gather evidence to learn about the Earth.

Embracing the shore of Lake Michigan, Kohler Park Dunes contains active and stabilized lake dunes, interdunal wetlands, and a small dry-mesic white pine forest. More than one mile of Lake Michigan beach is included in this State Natural Area.

One of the things that makes Great Lakes dunes so special is the origin of the sand. The sand at one time was not sand but very old bedrock found in the upper Great Lakes region and Canada. Millions of years ago, glaciers covered the area. Through time the glaciers caused rock to move, scraping the surface of the land. The scraping action loosened rock and broke it down into smaller pieces. As the glaciers melted they washed great amounts of rocky debris into lakes and rivers. The rocky debris eroded until it became what we know as dune sand. Most Great Lakes dunes were formed mainly during high water of the Nipissing period, about 4,000-6,000 years ago.

Great Lakes dune sand is made up of three different types of rock from the Upper Great Lakes and Canada:

87-97% Quartz

10-11% Feldspar

1% - 3% Magnetite

As the glaciers melted away dune sand was deposited across the land. Rivers that flowed from inland areas of the state out to the Great Lakes carried sand with them out to shoreline areas. The rivers deposited the sand into the Great Lakes, often where large bays had formed. The large deposits of sand in the Great Lakes created sandbars. The sandbars continued to build up with sand and as the water levels of the Great Lakes got lower the sand was exposed.

A sand dune needs the following three things to form:

1) A large amount of loose sand in an area with little vegetation such as a sandbar

2) A wind or breeze to move the grains of sand

3) An obstacle that causes the sand to lose momentum and settle. This obstacle could be as small as a rock or as big as a tree.

Where these three variables merge, a sand dune forms. As the wind picks up the sand, the sand travels, but generally only about an inch or two above the ground. Wind moves sand in one of three ways:

1) Saltation: The sand grains bounce along in the wind. About 95 percent of sand grains move in this manner.

2) Creep: When sand grains collide with other grains causing them to move. Creep accounts for about 4 percent of sand movement.

3) Suspension: Sand grains blow high in the air and then settle. About 1 percent of sand moves this way.

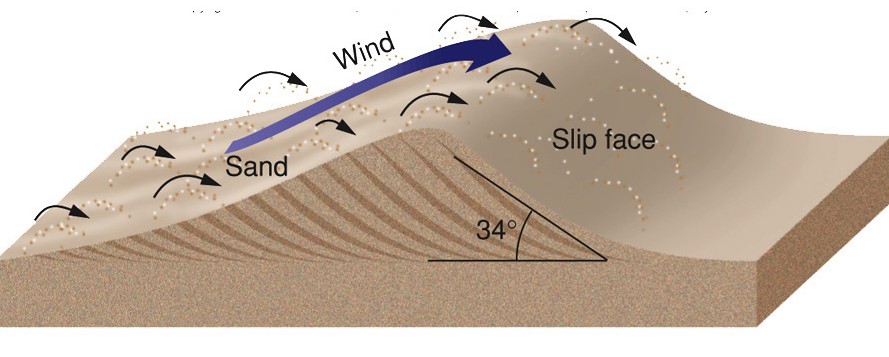

Once it's in motion, sand will continue to move until an obstacle causes it to stop. The heaviest grains settle against the obstacle, and a small ridge or bump forms. Because the obstacle breaks the force of the wind, the lighter grains deposit themselves on the other side of the obstacle. In this way, sand continues to pile up. As the wind moves sand up to the top of the sand pile, the pile becomes so steep it begins to collapse under its own weight, and the sand avalanches down the back side or slip face. The pile stops collapsing when the slip face reaches the right angle of steepness for the dune to remain stable. This angle, which scientists call the angle of repose, is usually about 30 to 34 degrees.

After enough sand builds up around an obstacle, the dune itself becomes the obstacle, and it continues to grow. Depending on the speed and direction of the wind and the weight of the local sand, dunes will develop into a different shapes and sizes. Stronger winds tend to make taller dunes; gentler winds tend to spread them out. If the direction of the wind generally is the same over the years, dunes gradually shift in that direction. Any vegetation that crops up will stabilize the dune and prevent it from shifting.

Interdunal wetlands occupy wind-created hollows that intersect the water table within active dune fields along the Great Lakes shores. They may also occur where moving sand encroaches on nearby wetlands, surrounding and isolating all or portions of them. Several interdunal wetlands here (called pannés) are thickly vegetated with lakeshore rush and sedges. Some of the common plants that stabilize the dunes are sand reed, marram grass, Canada wild rye, northern wheat grass, common and trailing junipers, sand cherry, and willow species.

From I-43, head east on V straight to the park. At the park office, you will have to pay for parking ($7 daily or $25 annual for Wisconsin residents) if you don’t already have a Wisconsin State Park admission sticker. It is suggested that you request a Park & Campground Map which also includes additional park regulations. At all times while you are walking along the trails, please stay on the boardwalk/cordwalk.

From the office, head south on Sand Dune Drive and make a left onto Sanderling Lane. This will take you to the parking lot of the Sanderling Nature Center. In the SouthEast corner of the parking lot, you will see a sign which says “Welcome to the Creeping Juniper Trail”. This is where you will start your walk, paying attention to informational signs along the way. See Additional Waypoints below for locations of each sign.

In order to get credit for a find on this EarthCache, you MUST first send answers for these 4 sets of questions to the cache owner (NOT in your “Found It” log):

Q1) Sand From Ice

What lobe of what glacier gouged out the basin that would become Lake Michigan? How long ago was that?

Q2) How Dunes Form

Where do dunes migrate? Where do you find the younger ones and where do you find the older ones?

Q3) Dune Stabilizers

What is the first plant to take root in the young dunes? What helps this plant hold sand in place?

Q4) Blowing in the Wind

How do sand blows develop?

Additionally, you must also provide the answers to one of these sets of options:

Option 1 : Three More Stops on the Creeping Juniper Trail

1A) Rare Plants

What 2 rare plants help stabilize the dunes?

1B) Largest Dune Tree

What kind of tree is this? What allows it to grow so far south?

1C) A Plant for…

What migratory animal stops here for food? What is the food it requires?

Option 2 : Hike South to a Scenic Overlook

Using the correct term identified in this text, what kind of area are you overlooking? How can you tell?

Option 3 : Hike North and Head to the Beach

From the north parking lot, follow the cordwalk east onto the beach. Measure the distance from the shoreline to the closest line of dunes, also known as the fore dunes. In addition to the measurement itself, tell me if these would be the oldest or youngest of the dunes.

Voluntary (no longer a requirement): Include scenic pictures of the dunes in your “Found It” log.

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)

Treasures

You'll collect a digital Treasure from one of these collections when you find and log this geocache:

Loading Treasures