Weathering of Limestone

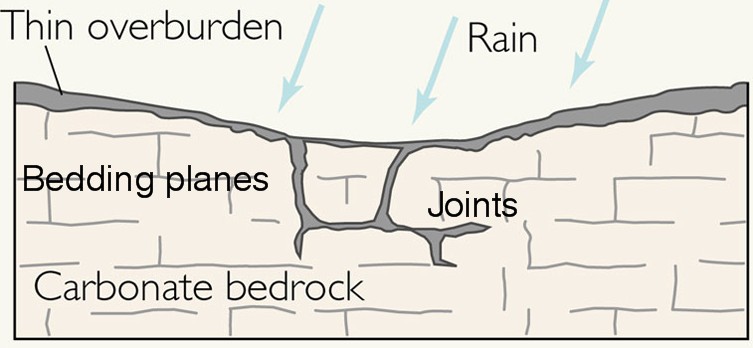

Limestone is largely made up of calcium carbonate in the form of

the mineral calcite. Limestone weathers by the solution of this

calcite. This occurs along the joints and bedding planes which are

present due to the sedimentary nature of the rock.

Diagram showing bedding planes and

joints

This causes the surface to become uneven, producing grooves

along the surface called lapies or karren. When these develop

further they are known as grykes (gaps), separating raised sections

called clints.

The area that you are directed to in this earth cache is

slightly unusual. You are not there to look at limestone pavement,

rather the differential effect of layers (strata) of rock that are

of a difference hardness or resistance to the elements of weather:

heat, cold and wet being three of the main ones.

What effects weathering?

A rock's composition has a great effect on its rate of

weathering. Rocks that are softer and less weather-resistant tend

to wear away quicker than those that are crystalline (igneous rock)

or have been subjected to more heat and pressure (metamorphic

rock). When the more weather-resistant rock is left behind, this

process is called differential weathering.

A rock's exposure to the weathering elements and its

surface area can affect its rate of weathering. Rocks that are

constantly bombarded by running water, wind, and other erosion

agents, will weather more quickly. Rocks that have a large surface

area exposed to these agents will also weather more quickly. As a

rock goes through chemical and mechanical weathering, it is broken

into smaller rocks. As you can imagine, every time the rock breaks

into smaller pieces its surface area or part exposed to weathering

is increased.

Think about a cube, which has both volume and surface area. To

find the surface area of a cube, you need to calculate the sum of

the areas for all six sides. Let this cube represent our rock that

is exposed to weathering. Already our cube has six sides that are

exposed to the elements. If we split our cube into eight smaller

cubes, then the total surface area would be doubled. Although the

surface area increases, the volume remains constant. Splitting the

eight smaller cubes in the same way would have the same effect; the

surface area would again be doubled. Increased surface area causes

rocks to weather more rapidly.

With thanks to edhelper

Education

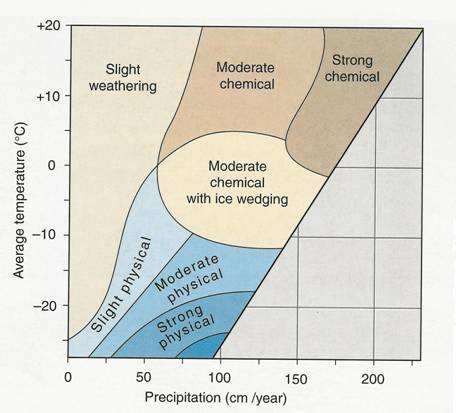

Graph showing differential weathering

rates

The above graph, a Peltier diagram, shows how weathering is

affected by temperature and rainfall (precipitation). Loius

Peltier, an American physicist in 1950 and climatologist in 1950,

predicted the rate and type of weathering that would occur from

mean annual temperatures and mean annual rainfall.

There are 3 major types of weathering, physical and

chemical.

1. Physical weathering is the breakdown of minerals, which

remain the same; there are 5 major subtypes:

a. Block or Granular disintegration results in blocks

of the parent material falling from the cliff and often increases

the surface area susceptible to attack.

b. Freeze-thaw action can effect water in the cracks in rocks,

freezing and expanding in volume by around 10% (in fact 9.05%)

where diurnal temperature variations include crossing freezing

point.

c. Exfoliation happens when there are changes in temperatures with

a diurnal range of 50 to 70 °C which is very possible in deserts.

Because rocks are relatively bad conductors of heat, only the

outside few millimetres are affected. Also known as ‘onion

skin’ weathering or differential expansion as different

colour minerals expand and contract at different rates.

d. Dilation is the expansion of rocks (doming) by removal of

overburden such as happens when ice sheets melt.

e. Salt weathering happens in the presence of saline solutions and

causes crystals to grow, particularly in shady conditions. This

causes flaking of surface or in small weathering pits and is faster

in marine locations.

2. Chemical weathering is most intense in warm, wet climates.

High temperatures promote chemical reactions and heavy rainfall

provides the necessary moisture. This results in the alteration of

the chemical composition of the weathered material due to a

reaction which alters:

a. the composition of rock minerals

b. the volume of the rock

c. the strength and coherence of the rock

It tends to be concentrated at the rock surface or along joints

and bedding planes. Block weathering and granular disintegration

can also be the result of chemical weathering.

There are 3 major products if chemical weathering:

a. secondary minerals

b. resistant minerals e.g quartz

c. soluble products

The result of weathering is often known as regolith and is often

composed mainly of unweathered and/or insoluble residues such as

quartz sand and pebbles.

Chemical weathering is capable of penetrating more deeply into

the rock than physical weathering and is particularly effective

where rock is alternately wetted then dried. An example of this can

be where there is seasonal fluctuation in the water table. Another

example is Carbonation. This particularly affects limestone as it

is altered to calcium bicarbonate which is taken into solution and

re-precipitated as tufa, or calcite to form stalactites,

stalagmites and helictites.

A key element in weathering is the presence of water.

Solution/dissolution obviously occur, also acts as a medium for

transporting acids etc.

Hydration affects rock minerals which have the capacity

to take up water. They increase in volume, which sets up stresses

within the rock e.g conversion of iron oxides to iron hydroxides.

This can cause surface flaking, similar to salt weathering.

Hydrolysis is a complex reaction affecting minerals in

igneous or metamorphic rocks e.g feldspar in granite – known

as rotting – and produces potassium hydroxide and

alumio-silicic acid. The former is carbonated and removed in

solution. The alumio-silicic acid breaks down into clay minerals,

notably kaolinite (china-clay) and is removed in solution. This is

also known as spheroidal weathering, as it rounds off corners and

affects statues, gargoyles etc.

Feldspar + hydrogen ions + water = clay + dissolved ions

4KAlSi3O8 + 4H+ + 2H2O = Al4Si4O10(OH)8 + 4K+ + 8SiO2

Oxidation is the reaction between rock minerals and

oxygen (usually dissolved in water) and changes the colour on

brickwork

4Fe + 3O2 = 2Fe2O3 (iron oxide or hematite) Reactions are

speeded up by warmth.

Chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff said that the speed of a

reaction increases by 2½ times when the temperature rises by 10°C,

so chemical weathering is greater in humid tropical climates in the

main.

3. Biological weathering is the effect of living things

such as tree roots: as a tree grows, its roots extend into the

ground. As they grow and thicken, rocks are prised apart. Ivy

growing on a building can loosen the bricks. It also occurs on a

slower, smaller scale where mosses and lichens overlay rock.

a. Decomposition produces humic acid and this

can result in the process of Chelation, the break down of

rock minerals by organic acids. Humic acid can also be produced by

excreta, especially where large areas rock are occupied by large

colonies of seabirds such as gannets

b. Respiration by plant roots increases carbon dioxide in

soil and assists the formation of weak acid as rainwater filters

through the soil. Trees extract water from soil which can lead to

shrinkage and ground subsides.

c. Burrowing animals such moles break up the rock and bring

material to the surface where it is exposed to chemical weathering.

Crustaceans on rocks at the coast bore holes in rocks and

secretions of shellfish increase rate of weathering

d. Trampling. Elephants trampling vegetation in game

reserves in Zambia and Namibia have led to soil erosion which

exposes bedrock which is then affected by weathering.

Other important factors

1. Rock Type

2. Rock strength and hardness

3. Minerals in the rock formed under high temperature and pressure

weather most quickly because they are ‘furthest’ from

the conditions in which they were formed. Some rocks are

‘harder’ than others.

4. Chemical composition - The presence of silicate minerals is

important. More stable minerals tend to be lighter in colour.

5. Rock texture - whether it is coarse grained or fine grained. In

finer grained rocks, the bonding is stronger, but the boundaries

between crystals form lines of potential weakness or cleavage. Fine

grained rocks often weather quicker.

6. Joints and bedding planes: these allow access to the

water.

7. Vegetation type.

8. Topography: slope angles, and aspect

With thanks to Peachnut

Education

For more information, click

here

To log this cache:

- Find out, using the Peltier diagram above, what type of

weathering is most likely to be affecting the cache area

- Take a photo of the small cliffs nearby the rock that you are

directed to with your GPS and/or you and post it to this page

- Count how many obvious layers there are in the rock you are

directed to

- Email me with the answers to log this cache

Please do not post images of the actual cache

on the website

Official EarthCache Banner