You’ve seen the big granite boulders along

the beach, on the side of Lion’s Head, and even in Paarl.

Seasoned Cape geocachers have learned a bit about the cape granites

from other earthcaches (for example:

Froggy Pond Boulder Hop,

Darwinian Contact &

Paarl Rock ), but how did these big bubbles of stone end up

looking the way they are? Where did they come from? The answer is

erosion. Different kinds of rocks erode differently, and at this

earth cache location you will be able to see granite in the process

of eroding.

When the Cape Granites intruded into the

Malmesbury shale, deep under the earth, around 540 million years

ago, they were liquid rock. They cooled slowly forming massive

bodies of granite with large crystals of feldspar, called

megacrysts because they are so unusually large. These bodies of

granite were huge, mountain sized pieces of rock. Later, the Table

Mountain Sandstones (TMS) were deposited on top of these rocks.

But how did these mountain-sized pieces of granite end up as the

characteristic bubble shaped boulders that are so prominent around

the peninsula? They didn’t roll there. Rocks are broken down

by different kinds of erosion into smaller particles that

eventually form sand and dirt. For the granite around Cape Town,

the two most important factors of erosion are fracturing and

chemical weathering caused by water.

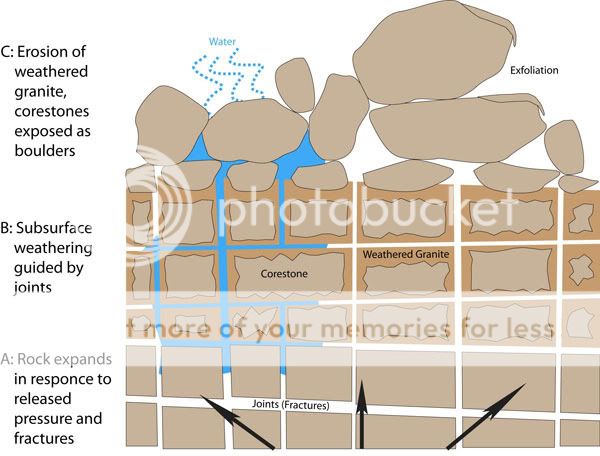

When a body of rock is uplifted, and the layers

above are eroded away, a great weight has been lifted off their

backs. This causes fracturing to occur and joints to appear (See

Figure: A). Water seeps into these joints eroding the rock at these

seams. The more water that can get in, the faster the crack widens.

The large feldspar crystals are altered by acidic water and become

kaolinite, a soft clay mineral. The once rock hard granite can now

be crushed with your bare hands. The resulting kaolinite is mined

around the Cape Region for making ceramics and glossy paper. The

granite blocks that do not erode away are left in place and

referred to as corestones.

At the cache location there is a road cut where

you can see corestones of solid granite in place surrounded by the

transformed eroded granite (See Figure: B). At the cache location,

or maybe in the parking lot next to it to avoid the cars, take a

handful of this eroded granite and crush it in your hand. You will

be able to see the components of granite and the fine powder of the

kaolinite.

Now if you look up at Lion’s Head from the

cache location, you will be able to see large granite corestones

exposed on the surface of the hill. Unlike the corestones that are

still buried in the road cut, these rocks are rounded like those

down at the beach. Why does that happen?

The answer is in the nature of the rock. Granite

is an igneous rock, this means it was molten before it formed.

Unlike sedimentary rocks, that are laid down in layers, igneous

rock does not have any internal structure for cracks to appear in a

regular, predictable way. As a result, when granite weathers, it

exfoliates (See Figure: C). What this means is that it peels off in

layers like the skin of an onion, resulting in a rounded shape.

There are also granite boulders that while

rounded, also seem to be hollowed out inside. I saw quite a few of

these near

Blood Sweat and Sandy Bay recently with Cism. There is also a

stunning example up by the picnic table at

Shrek's Boulder and these kinds of rocks can be found many

other places around the cape. Apparently these unique features are

formed when there is a pervasive wind direction in addition to the

usual methods of eroding granite. As CapeDoc knows, Cape Town has a

pervasive wind direction. What happens is that the water on one

side of the boulder is dried quickly by the wind, and the other

side stays wet longer. This causes the downwind side of the boulder

to erode faster. Once started, a concavity forms and becomes its

own wind shadow, increasing the rate of erosion. Over time, the

rounded granite boulder becomes a hollowed out shell, forming a

perfect hidey hole to place a cache.

To log this earth cache, please email me the answers to the

following questions:

- Based on your direct observations, did the granite here cool

slowly or quickly? How do you know?

- What colour is the powder produced by crushing the eroded

granite?

- Why does granite erode into balls instead of into slabs?

- What will happen to the blocky corestones in the road cut when

the surrounding degraded granite eventually erodes away?

- If you want, take a picture of yourself or your GPS at the EC

location and include it in your log, (THIS IS OPTIONAL)

Sources and further reading:

Compton, J.S. 2004. The Rocks & Mountains of Cape Town.

Double Story, Cape Town.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_geology_of_the_Cape_Peninsula_and_False_Bay

http://www.travelwild.com.au/the-wild-guide/geology-of-remarkable-rocks-kangaroo-island.php