Big Thicket National Preserve, located in Southeast Texas, is managed by the National Park Service. Big Thicket National Preserve became the first national preserve in the National Park system when Congress authorized it on October 11, 1974 to protect its complex biodiversity. What is so extraordinary is not the rarity or abundance of species, but how many species coexist here. Because of its geologic history, major biological influences collide in the Big Thicket. There are 85 tree species, over 60 shrub, 20 orchid, and four insect-eating plant species. Nearly 1,000 other flowering plant species and 26 fern and allies are also found here. Some 185 bird species live here or migrate through. Fifty reptile species include a small, rarely seen alligator population. Frogs and toads abound. The preserve consists of nine separate land units and six water corridors. The Visitor Center (above) is open 9am – 5pm daily. HINT: The coordinates for the Visitor Center are on the student’s T-Shirts in the pictures!

Big Thicket National Preserve, located in Southeast Texas, is managed by the National Park Service. Big Thicket National Preserve became the first national preserve in the National Park system when Congress authorized it on October 11, 1974 to protect its complex biodiversity. What is so extraordinary is not the rarity or abundance of species, but how many species coexist here. Because of its geologic history, major biological influences collide in the Big Thicket. There are 85 tree species, over 60 shrub, 20 orchid, and four insect-eating plant species. Nearly 1,000 other flowering plant species and 26 fern and allies are also found here. Some 185 bird species live here or migrate through. Fifty reptile species include a small, rarely seen alligator population. Frogs and toads abound. The preserve consists of nine separate land units and six water corridors. The Visitor Center (above) is open 9am – 5pm daily. HINT: The coordinates for the Visitor Center are on the student’s T-Shirts in the pictures!

INTERNATIONAL BIOSPHERE RESERVE, 1981, United Nations

GLOBALLY IMPORTANT BIRD AREA - 2001, American Bird Conservancy

[Big Thicket] is hard to explain. It has no commanding peak or awesome gorge…Its appeal is more subtle. It must be experienced bit by bit, step by step. One can neither see far nor go fast. A hundred yards off the road without a compass and you are lost…Its wilderness character was, and still is, its essential appeal.

Big Thicket Legacy, Loughmiller, 1977

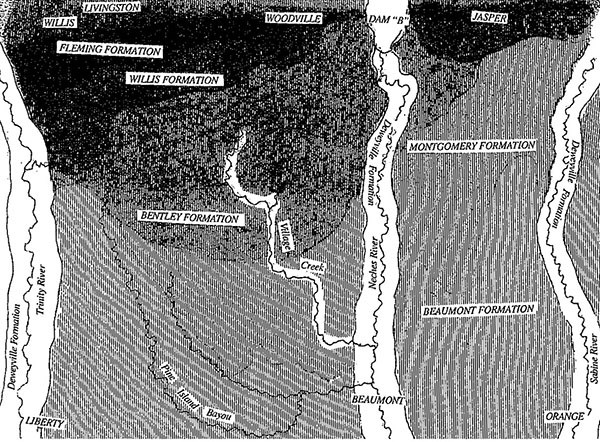

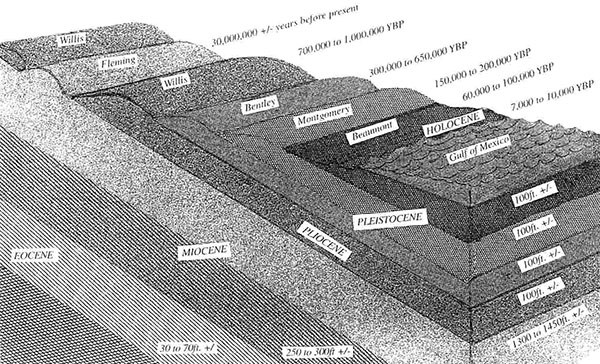

By geological time, Big Thicket is a young tilted topographical basin. Its surface formations were deposited in the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs of the past few millions of years. During the Pleistocene epoch four major glacial stages influenced sea levels. As the great ice masses grew or melted sea level fell or rose accordingly. The glaciers did not reach this far south, but were responsible for the landforms and nature of the Big Thicket.

During warm periods with high sea levels, the land flooded and rivers deposited vast deltas and alluvial plains of mud, sand, and silt on the seabed. When the ice returned and the sea level fell, erosion cut in to the newly deposited sediments. Over millennia, the weight of increasing sediments caused the land to subside, slanting the layers down toward the Gulf of Mexico. These layers are exposed as broad, irregular bands paralleling the gulf, with the oldest layers to the north and the youngest along the coast.

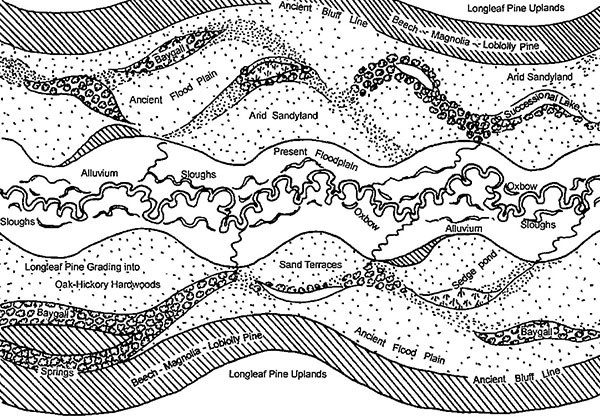

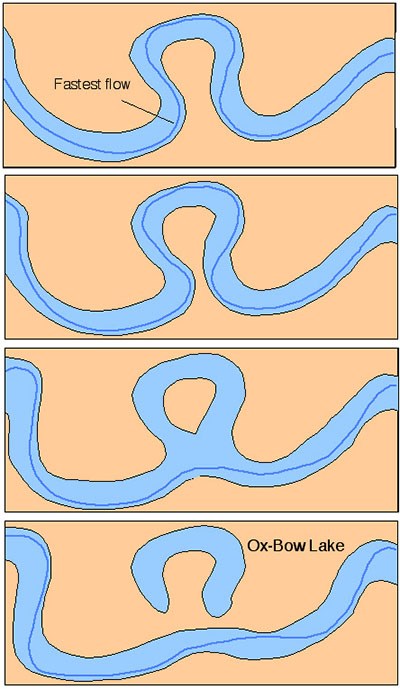

This geologic process created an area of surprising hydrologic and soil complexity, despite the lack of topographic relief. Shifting and abandoned stream channels, sandy levees, oxbow lakes, and old river terraces contribute to the complexity. The diversity of different strata/parent materials result in a variety of soil and microhabitat conditions from well drained ridges to bogs and from highly acidic to basic soils which have profound effects on the vegetation.

The Bruin Slough EarthCache is located on the Kirby Nature Trail. Geology here is expressed by the plants that can survive in certain conditions. As you hike the trail you will pass through several distinct plant communities. Just a few inches of soil or a subtle increase in acidity can change the forest. This EarthCache was researched and created by students of West Brook High School, Beaumont, Texas through a grant from the National Park Foundation. The students named the cache after their school mascot, the Bruin, which also brings to mind the black bear (Ursus americanus) that once roamed these woods. Click here for a Kirby Nature Trail Map.

- The trail is not paved and tree roots are exposed – please watch your step.

- Do not attempt this hike if any part of the trail is underwater. Floodwater will completely cover submerged bridges, and the bridges will become slippery. Drop-offs exceed ten feet.

- Watch for snakes along this trail and give them plenty of space.

- Bring insect repellent.

- Watch for bee, wasp and fire ant nests.

- Please pack out all trash and keep pets on a leash

.

.

- Beware of poison-ivy (Rhus radicans). Leaves of three, leave them be! Don’t touch any of the hairy vines that are growing on the trees because they are poison ivy, too.

- Collecting plants is prohibited.

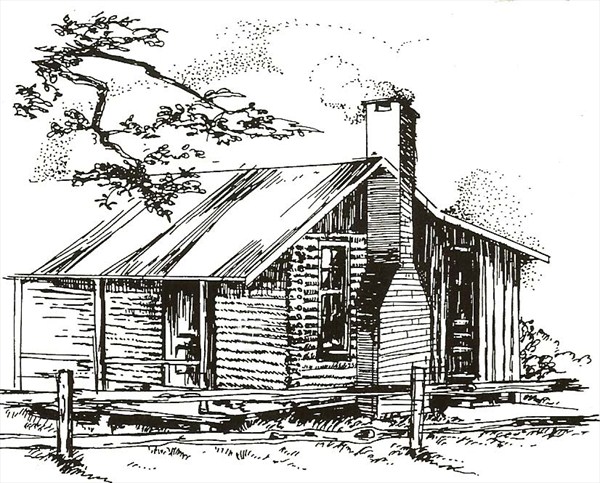

The Kirby Nature Trail begins behind the Staley cabin - an historic cabin built in 1934, when FM 420 was a primitive dirt road and virgin timber was hauled out by teams of oxen. Mrs. Staley planted some ornamental trees, including the large live oak in front of the cabin. Water was obtained from a hand drawn well. In addition to a small garden and some fruit trees behind the cabin, the Staley’s kept a ten acre field for cows and crops about one mile south. Hogs ranged free in the woods and were rounded up each year using horses, dogs, and a lasso.

The many fallen trees you will see along the trail came down in Hurricane Rita 2005 and Hurricane Ike 2007.

Slope Forest:

The slope forest is a well developed, closed canopy forest of upland hardwoods. As you walk down the trail, you notice that in this community the trees and plants are on a gentle, well drained incline, hence the name “slope forest.” The sandy soil is heavily leached by the abundant rainfall which makes the soil relatively low in nutrients and tends to be acidic. One of the predominant trees found in the slope forest community is the American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). Its smooth bark is often splotched with lichens. Heart rot may hollow out the base of beech trees, providing shelter for small animals. Squirrels and other mammals eat the small beechnuts, which ripen in the fall.

West Brook High School Students on the Kirby Nature Trail.

Another common tree found in the slope forest community is the Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora). Like the pine, the magnolia is also a conifer, but has broad leaves and, unlike most broad leaved trees, is evergreen (it does not shed its leaves in the winter). The tree is decorated in the spring with large, waxy white and fragrant blossoms. Magnolia cones contain many red seeds, each attached by a cotton-like thread. Squirrels eat these seeds as part of their autumn diet.

Another common tree found in the slope forest community is the Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora). Like the pine, the magnolia is also a conifer, but has broad leaves and, unlike most broad leaved trees, is evergreen (it does not shed its leaves in the winter). The tree is decorated in the spring with large, waxy white and fragrant blossoms. Magnolia cones contain many red seeds, each attached by a cotton-like thread. Squirrels eat these seeds as part of their autumn diet.

The most common tree found in the slope forest is the Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda). Pine stumps along the trail are the remains of timber cut before the preserve was established. The smaller plants that you may see in this community in the spring are Wake-robins (Trillium gracile) and Jack-in-the-pulpits (Arisaema triphyllum). These plants depend on the larger community members for shade and soil conditions created by decaying leaves.

Baygall:

A baygall is a very wet area, named for sweet bay (Magnolia virginiana) and gallberry holly (Ilex coriacea) trees which often grow here. The trunks of the tupelo tree (Nyssa spp.) and the sweet gum tree (Liquidambar styraciflua) bell out near the base to form a buttress. This buttressing occurs where the trees grow in water, an adaptation to stabilize the tree in the wet soil.

Baygalls form at the bottom of slopes and collect the rainfall drainage after it runs through the leaves and detritus. This makes the water in baygalls highly acidic as it leaches tannin from the fallen leaves which stains the water a clear, almost black color with a pH as low as 4.5. The slow decay of leaves on the muddy bottom sometimes causes gas bubbles to rise to the water’s surface. A number of water-loving plants flourish in or around the edge of the acidic, low oxygen water in the baygall. Because of the acidity of the soil, wild azaleas (Rhododendron conescens) thrive and produce showy pink blossoms in early spring.

Cypress Slough:

Westbrook EarthCachers are standing in the slough (left) during the 2011 drought, usually the slough holds some water.

A cypress slough forms along the edge of a creek or river where it originated, sometimes as a result of the waterway changing course. When the channel meanders to the point of cutting across the curve, it is called an oxbow. During high water the stream flows through the slough, then back to the creek further downstream. Cypress sloughs drop slightly in elevation and the soil is fertile, sandy or silty loam. The dominant species, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), often grows in standing water; can be 130 feet tall and live up to 1,200 years. With average rainfall, the slough will contain water most of the year. Upright growths called “knees” rise from cypress roots and serve an unknown purpose for the tree. Some theories suggest the knees help in aeration or serve to balance the tremendous weight of the tree in the wet soil.

The bald cypress is a conifer (produces cones) with short, fine needles and small round cones. Unlike most conifers, it is deciduous since the needles drop every fall, thus, the common name “bald cypress”. These cypress trees support two epiphytes: Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) and resurrection fern (Polypodium polypodioides). Epiphytes are plants that depend on nutrients and moisture carried by the air. Spanish moss is a member of the pineapple family, and is a gray hairy plant that often drapes over branches. Resurrection ferns are more visible on the higher branches of the cypress during winter. Because these plants live on air, they are easily affected by air pollution.

River Floodplain:

Adjacent to the creek is the flood plain community. As the name implies the low lying forest along the creek floods regularly with the 55 inch average rainfall in Southeast Texas. The periodic flooding produces a fertile sandy or silty loam soil and provides additional water for the plants. A dense forest canopy grows in the flood plain, dominated by oaks and sweet gum (Liquidamber styraciflua). River cane (Arundinaria gigantean), our only native bamboo, and inland sea oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) grow beneath the trees in the floodplain community because they can withstand the frequent flooding which prevents many other lower canopy plants from living here.

Cut Bank:

A cut bank is an erosional feature of meandering streams. Located on the outside of a stream bend where the water runs the fastest, the stream cuts into the layers of soil creating a small cliff. Cut banks are unstable and the water below is fast and deep, always use caution. Over time, through floods, trees and poorly placed buildings can fall into the stream as it meanders through the floodplain. On the inside of the stream bend slow moving water deposits sediment forming a point bar. The erosion of cut banks and the deposition of point bars can lead to the formation of an oxbow lake or cypress slough. Geologically this is an area of high energy. Soil eroded here will be deposited on point bars downstream.

Wildlife:

Many different species of wildlife live in the Big Thicket. You might encounter deer, lizards, raccoons, birds, insects, and even the nine-banded armadillo. Like raccoons, nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) prefer to feed at night. The armadillo roots up leaves on the ground to look for insects, ants, beetles, spiders or an occasional lizard or salamander.

Many different species of wildlife live in the Big Thicket. You might encounter deer, lizards, raccoons, birds, insects, and even the nine-banded armadillo. Like raccoons, nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) prefer to feed at night. The armadillo roots up leaves on the ground to look for insects, ants, beetles, spiders or an occasional lizard or salamander.

Animals are more difficult to see after the trees leaf out in spring. You may have better luck in clearings or along creeks if you approach quietly. Signs of animals are everywhere if you just look for the clues. Some common signs you might see include leftovers from a meal, tracks in the mud, scat on a log or trail, or nests and homes.

Some of the most common birds found in the Big Thicket are woodpeckers. Woodpeckers use their specially adapted feet and tail to climb and move around vertical tree trunks. They chisel holes in trees or snags, hunting for wood-boring insects. Sapsuckers drill neat rows of holes in rattan vines and trees to let sap collect. With its brush-like tongue, the sapsucker sweeps up bugs attracted to the sap. Pileated, redheaded, red-bellied, and downy woodpeckers, as well as yellow-bellied sapsuckers are often seen on the trail.

Spring is the best time of year to hear bird sounds. The Northern parula (Parula americana) sounds like a zipper on a tent. You may also hear the Acadian flycatcher (Empidonax virescens) screaming for “Pizza!”.

To get credit for the Bruin Slough EarthCache send the answers to these questions:

1. Looking north from the coordinates, estimate the width of the slough.

2. Find a massive cypress tree with bumps up and down the lower portion of the trunk.

What direction from ground zero is this tree?

Follow the trail to N 30 28.216 W94 20.797 – Face East on the middle of the bridge.

3. Which side of Village Creek is the cut bank?

4. Which side of the creek is the point bar?

SPECIAL THANKS:

Big Thicket National Preserve, Will Watkins

Big Thicket National Preserve, Will Watkins

National Park Foundation

National Park Foundation

West Brook Senior High School, Environmental Systems class of 2011,

Cynthia Parish, and Dylan Hall

HONORARY FIRST TO FIND!

BizzyB, Mudfrog, ScubDo