For starters you won’t be able to do the earthcache

observations if the Little Miami river level is too high. Check

here for the river level.

Little Miami River Level

The river was at 5.5 feet when I made my observations. If the

water is a few feet higher and the GZ will be under water and you

won’t be able to take your measurements. You should be

standing in the middle of the rock “beach” on the shore

of the Little Miami River. Note for paperless cachers – this

might be one cache worth printing out to help with the field

work.

There is no need to bushwhack. There is a well-defined trail in

Avoca park that starts at N 39° 08.343 W 084° 20.478 Parking is

near there too. This is why I selected this spot – easy

access!

Where you are standing is a point bar of a river meander or a

sharp bend in the river. For more info on how meanders are formed

and their features visit GC36NKM. Both this

“beach” of rock and the deeply eroded bank on the

opposite side were formed by the two processes that shape river

geography, erosion and sedimentation. What we are going to do at

this spot is to quantify the driving force of erosion: the velocity

of the water!

When the river is at flood stage, very fast moving water scrubs

the point bar you are standing on. Note the uniformity of the rocks

at this spot. They are all scrubbed white – no algae, no dirt

on the rocks. They are almost entirely composed of rocks that have

sides eroded round by the erosive power of the water. They also

almost have a distinctive shape: mostly flat. It is the fast

flowing flood water that basically “sorts” these rocks,

leaving these here on the bank while washing others downstream or

left deeper in the channel bed. The flow also scrubs off the dirt

and smaller particles like sand off this area. The only smaller

rocks you see might be lodged under some of the larger ones.

Henning Filip Hjulstrom was a Swedish geographer who started

quantifying the processes that form features like this point bar.

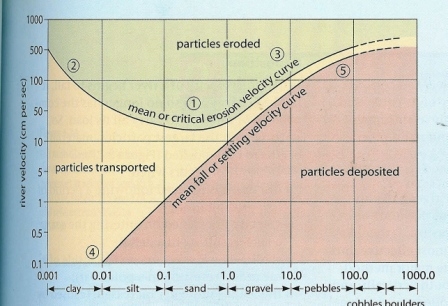

Below is a notional version of the diagram he and his students

later developed to quantify erosion and deposition of river

materials.

This is a graph that shows the relationship between the size of

sediment and the velocity required to erode (lift it), transport it

and deposit it. The critical erosion curve shows the MINIMUM

velocity required to lift a particle of a certain size. The mean

fall or “settling” deposition curve shows the MAXIMUM

velocity at which a river can be flowing before a particle of a

certain size is deposited. The zone in-between is the zone of

transport. Note the velocities for transport are lower than that

for erosion, because it takes much more energy to lift sediment and

start its motion than to maintain it in transport. Note that the

graph is logarithmic, not linear. On this scale you can see that

from 1mm to 100mm the “transportation” velocity, or the

velocity that a particle will be moved, is linear relative to

particle size. But below 1mm the relation between particle diameter

and velocity is not as well correlated.

This curve shape is due to the fact that there are two different

regimes covered by the graph. For particle sizes where friction is

the dominating force preventing erosion (1-100mm) the graph is

linear. But for cohesive material like clay and silt, the erosion

velocity increases with decreasing grain size, as the cohesive

forces (electrostatic) are relatively more important. Note the

consistency of the material under/between the rocks – thick

clay and mud.

Estimating River Velocity

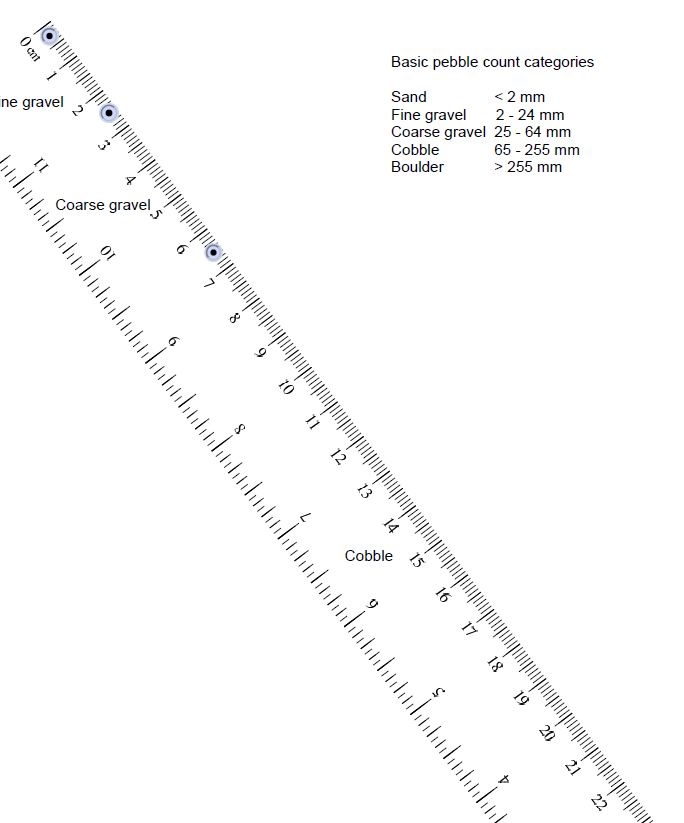

We are going to use the graph below to estimate the water

velocity scrubbing this point bar. From where you are standing try

to find the smallest rock that is on the top layer. We’ll

assume the water current was fast enough to wash away anything

smaller. The motion of rocks along the bottom of a river is called

“bed load”. The curve lists “diameter” and

assumes spherically shaped objects (sand perhaps), but the rocks at

the GZ are more ellipsoid in shape – like the diagram below.

So we’ll come up with an equivalent diameter.

For you paperless earthcachers, I’ll try to describe the

dimensioning. Almost all the rocks you’ll see around you are

relatively flat on one side with an oval shaped face. Dimension

“C” is the thinnest dimension between the 2 flat faces.

If you look at the oval face of the rock “A” is the

longest dimension and “B” is the direction

perpendicular to “A”. (If you printed out the cache

listing there’s a scale at the bottom.). Measure B and C. (If

you don’t have a scale and didn’t print this out you

could take a photo next to your GPS to scale it on the computer

screen.)

We’ll assume the rocks tend to line themselves up with the

water flow such that water flows along the “A”

dimension. Then the “B” and “C” dimensions

set the ellipse shaped cross section of the rock. The chart lists

velocities based on diameter so we’ll estimate the equivalent

diameter based on cross sectional area. The circular cross

sectional area of a sphere is where D is the diameter =

Π[pi]x(D)(D)/4 for our ellipse it is Π[pi] x(B)(C). So

measuring the dimensions B and C for the rock - use the following

to calculate the equivalent diameter for the chart.

√ (4)(B)(C)

[Again for you paperless cachers that’s square root of the

product 4xBxC.]

With this “effective” diameter you can go into the

detailed Hjulstrom curve and pick off the velocity of the water

that it would take to move it. Remember it’s a log/log

curve.

Now we’ll add one last scientific detail to our

calculation. We’ll also assume the coefficient of drag of the

flat rock (an ellipsoid) is one half that of a sphere (per

http://www.alepuniv.edu.sy/ev/uploaded_files/elibrary/files/file_667_828122.pdf)

so the water velocity to move an ellipsoid rock is twice what you

got from the curve. From that, you know that the velocity of the

water there is a little less, but not much less or smaller rocks

would be present.

To see a neat video of bed load transport - see the YouTube

video below.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3llzwvv1zc

To log this earthcache email me the answers to the following:

(Show your math!)

1) What are the dimensions of your rock (B and C)?

2) What is it’s equivalent diameter?

3) Which of the two curves on the Hjulstrom diagram do you use

to determine the velocity

required to start the motion of your rock that is at rest (this

is the curve to use to answer #4)?

4) What water velocity would it take to move your rock? (You can

convert to mile per hour using 1 centimeter/second = 0.022 369 362

921 mile/hour (mph))

5) The curve provided is for a water depth of 1 meter. Check out

the river bank. The wall of dirt marks the “bank full”

height of the river. When the river rises above this the water

spills out onto the vegetated flood plain above. So is the curve

applicable here?

6) Based on the charts how is your rock classified? (pebble,

cobble, etc) Use the sizing on the diagram not the ruler.

7) Optional: post a picture of yourself and your rock to

commemorate your visit!

Scale: