TO CLAIM A FIND FOR THIS EARTHCACHE...

You have to e-mail the answers to all the following questions to the cache owner.

1) What is the difference between the rock formations in Cutting 1 and Cutting 2? Also, identify the appropriate position of each of these rock formations and the process(es) that link them in the rock cycle as represented in the schematic diagram below.

2) If you were standing at Cutting 2 with blinkers on and only saw the rock formation right in front of you, how would you know it is colluvial and not alluvial? If this formation was to lithify what type of sedimentary rock will it form?

3) How do the quartzite xenoliths, which you can see plenty of at Cutting 2, differ from the surrounding sandstone? Think in terms of colour, shape, texture, hardness, etc.

4) Visitation confirmation: What is the date on the memorial across the road from the parking coordinates?

5) Optional: Please share your experience with the caching community by uploading photos of the site and/or your caching party, with your log.

ENJOY!

|

OVERVIEW

This is the SECOND of three earthcaches in the area that introduce geocachers to some of the most fundamental concepts of geology – “Earthcaching 101” if you would. This particular cache focuses on the rock cycle - a model which describes the relationship between the three basic rock types and the processes that drive this dynamic system. At the cache site you will be able to observe several of the rock formations and processes in the cycle as discussed below.

Important notes:

1) The published coordinates will take you to a suitable, save parking area between two different cuttings you will have to walk to. Cutting 1 is ~80m south of the parking area while Cutting 2 is ~70m north of it (refer to the additional waypoints for their exact positions).

2) Road cuttings give us a great view of what’s hidden below the Earth’s surface but unfortunately it also means they are, well... right next to a road! Although this particular road is usually quiet and has a low speed limit it is fairly narrow, so PLEASE BE CAUTIOUS – especially when caching with children.

THE ROCK CYCLE

Like most materials on Earth, rocks are continuously created and destroyed. The rock cycle is a model which describes the formation, transformation and breakdown of rocks and the processes responsible for this. It is one of the fundamental concepts in geology and describes the dynamic transitions among the three main rock types, i.e. igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic, through geological time. The two primary driving forces of the rock cycle are plate tectonics and the water cycle as illustrated in the landscape below.

Adapted from an artwork of the Council and Museum of Nature, Canada.

Adapted from an artwork of the Council and Museum of Nature, Canada.

Furthermore, the three main rock types are linked by two intermediary stages, i.e. magma and sediment, and various transformational processes, which either directly change the rocks (e.g. weathering) or expose them to new environments/conditions where changes are induced (e.g. subduction). Destructive processes (red arrows) include melting and weathering, while constructive processes (green arrows) include crystallisation (and re-crystallisation), compaction and cementation. All these relationships, processes and transformations can be summarised in a simple diagram as follows:

THE THREE MAIN ROCK TYPES

Earth’s rocks can be classified according to the processes that formed them:

Igneous rocks - start out as magma, i.e. molten rock, which solidifies/crystallises as it cools down in one of two very different environments (refer to the first figure above). Volcanic processes form extrusive igneous rocks which cool quickly on or very near the Earth’s cold surface and form rocks with a fine crystal structure, e.g. basalt. In contrast, intrusive igneous rocks cool slowly in well insulated plutons (a mass of igneous rock - Pluto was the Roman god of the Underworld) deep below the Earth’s surface and form rocks with large crystals, e.g. gabbro. Gabbro has the same chemical composition as basalt but a different crystalline structure and is therefore also a different mineral.

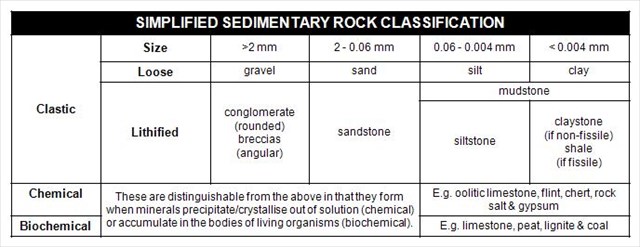

Sedimentary rocks - are mostly rocks made up of clasts, i.e. pieces, broken off other rocks (or grains). Weathering causes large rocks to break into clasts, which are then transported (erosion) by wind or water and deposited in a basin. After a period of time, the clasts are lithified (lithos is the Greek word for stone) through processes of compaction and cementation. Clastic sedimentary rocks are classified based on the size of the clasts from which they were formed; sandstone, siltstone and mudstone, for example, are comprised of progressively smaller clasts (see table below). Gravel, i.e. clasts of between 2 and 4000 mm, mixed with smaller particles can lithify to form conglomerates (if the gravel is rounded, for example as you’d expect to see in riverbeds) or breccias (if the gravel is angular and sharp-edged, for example as you’d expect to see at the bottom of a mountain slope).

In addition, some rocks form when minerals crystallise or precipitate out of solution or accumulate in the bodies of living organisms in a basin to form chemical and biogenic sedimentary rocks.

Metamorphic Rock - form when igneous, sedimentary or other metamorphic rocks are subjected to high temperatures and pressure during burial or contact with intrusive or extrusive magma, which induces changes to the rock’s mineral composition and texture ("meta" means change, and "morph" means form). These induced changes include: (i) new minerals that are formed at the expense of old ones and (ii) altered rock texture due to changes in the size, shape and orientation of minerals’ crystal structures. Quartzitic sandstone, for example, is metamorphosed to quartzite - the individual quartz grains recrystallise along with the former cementing material to form an interlocking mosaic of quartz crystals and most of the original texture and sedimentary structures of the sandstone are erased.

Regional metamorphic rocks form over vast areas, primarily driven by pressure, such as encountered at convergent plate boundaries. Contact rock metamorphosis, in contrast, is thermally driven and common along boundaries of igneous intrusions or under lava flow zones.

SELECTED PROCESSES AND LANDFORMS ASSOCIATED WITH THE ROCK CYCLE

Probably the easiest way to finish the “rock cycle puzzle” is to briefly define some of the most important processes, landforms and geological features associated with the cycle.

Alluvium: Loose, unconsolidated (not cemented together into a solid rock) sediment, which has been eroded, reshaped and deposited by flowing water in a riverbed, flood plain, or delta (non-marine environment). Usually well rounded and sorted (equal sized) clasts – forms conglomerate when lithified.

Cementation: The process by which clastic sediment is lithified by precipitation of mineral cement among the grains of the sediment.

Colluvium: Loose sediment that have been deposited at the bottom of a slope or against a barrier on that slope, transported by gravity. Usually angular, sharp-edged and unsorted clasts – forms breccias when lithified.

Compaction: Tighter packing of sedimentary grains causing weak lithification and a decrease in porosity, usually from the weight of overlying sediment.

Crystallisation: Is the process through which individual minerals in a solution or melt form solid, segregated crystals.

Deposition: The settling of sediments out of a transporting medium in a basin.

Erosion: The processes that loosen weathered clasts and transport them from one place to another on Earth's surface. Agents of erosion include water, ice, wind, and gravity.

Lithification: The process by which sediment is converted into sedimentary rock. This process includes compaction and cementation.

Magma: Molten rock, generally a silicate melt with suspended crystals and dissolved gases. Called lava after it has erupted from a volcano.

Metamorphism: Alteration of the minerals and textures of a rock by changes in temperature and pressure, and/or by a gain or loss of chemical components.

Sediment: Material (such as gravel, sand, mud and lime) that is transported and deposited by wind, water, ice, or gravity; material that is precipitated from solution; deposits of organic origin (such as coal and coral reefs).

Subduction: The process where one tectonic plate moves underneath another one, at a converging boundary, and sinks into the mantle.

Weathering: The processes by which rocks are chemically altered or physically broken into fragments/clasts as a result of exposure to atmospheric agents and the pressures and temperatures at or near Earth's surface, with little or no transportation of the loosened or altered materials.

Xenolith: A pre-existing rock fragment which becomes enveloped in a larger rock during the latter's development and hardening.

AT THE EARTH CACHE SITE

As you drive along Clarence Drive to this site the great majority of the rocks you’ll see are sedimentary. The magnificent cliffs above the road are all Table Mountain sandstone which was deposited as sandy sediments in what was then a relative shallow Agulhas Sea, approximately 500-410 million years ago (MYA). These sediments lithified and were later (~300 MYA) uplifted to form the Cape Fold Mountains, when a subduction zone developed along the southern margin of Gondwana and caused the northerly compression of the landmass.

Below at the water’s edge you can also sporadically catch glimpses of the oldest rocks you’ll be able to see in the Cape Peninsula and Boland area - the Malmesbury group sedimentary rocks. These rocks are in general more finely grained (i.e. mudstone) and darker coloured (blue-grey) than the Table Mountain sandstones which they underlay. The muddy sediments that formed these rocks are thought to have been deposited ~550 MYA in an ancient ocean basin called Adamastor. You will be able to clearly see these contrasting formations from the cache site, looking south (see photo below). You can also stop to inspect the Malmesbury rocks from up close at Gordon’s Bay (waypoint MalGB) and/or where Clarence Drive gets really close to the water’s edge (waypoint MalCD).

We chose this particular site as an earth cache site not only because you can see several of the features discussed above, but also because you can see part of the rock cycle “in action”! Cutting 1 is through solid sandstone close to the relatively unweathered crest of a ridge while Cutting 2 gives you a glimpse inside colluvium that accumulated at the foot of a similar ridge. The two cuttings therefore represent two different stages in the cycle, that being sedimentary rock and sediment, which are connected through the destructive processes of weathering and erosion. While the colluvium is the “eroded product” (clasts) of the solid-looking sandstone cliffs above it could possibly also be the “sedimentary beginning” of a new class of sedimentary rock if it was to lithify, i.e. breccia.

You will also be able to see many well rounded quartzite xenoliths within the sandstone clasts at Cutting 2; a further clue to Table Mountain sandstone’s watery origins. Quartzite, of course, is a hard metamorphic rock that originates from sandstone which is metamorphosed through heating and pressure to quartzite as discussed above. Close inspection of the xenoliths within their sandstone tombs will therefore give you an ideal opportunity to directly compare some of the changes which are introduced into the fabric of rocks through metamorphism.

Although granite intrusions have indeed occurred in the Cape Peninsula and are responsible for some of the most famous landmarks in the area, e.g. Boulders Beach and Paarl Rock, there are unfortunately no exposures close to this earth cache site. For examples of igneous rocks and their characteristics you’ll therefore have to look at earth caches such as Froggy Pond Bolder Hop right across False Bay or Paarl Rock north of here.

REFERENCES

http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/geo/basics/diagrams.htm

http://www.northstonematerials.com/about-us/education/basic-geological-classification/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_cycle

http://flexiblelearning.auckland.ac.nz/rocks_minerals/index.html