The logging questions can be answered from the areas open to the public; please observe park hours and regulations and all "area closed" signs.

There is no cell reception on Garden Key, plan accordingly. App users may want to download all earthcaches nearby before travel so the cache descriptions are fully available.

GEOLOGY OF THE FLORIDA KEYS

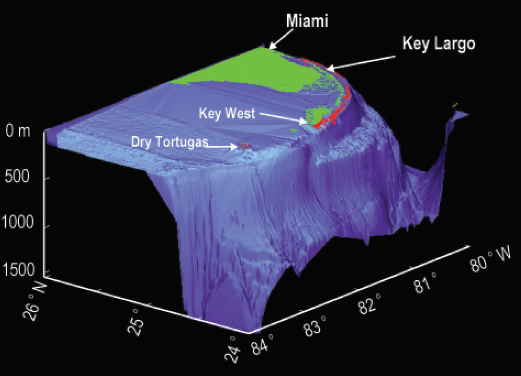

The Florida Keys lie off the southern coast of Florida, stretching along the very edge of the North American continental shelf. The Keys are divided into three distinct sections: upper, middle, and lower. These divisions correspond to their orientation, morphology, water depth, and composition. The upper Keys (from Soldier Key in the northeast to Lower Matecumbe Key in the southwest) are oriented almost north-south and buttress against the east-southeast winds. The middle Keys (from Craig Key south to Pigeon Key) are oriented northeast-southwest and face directly into the east-southeast winds. The upper and middle Keys are composed of Key Largo limestone, which is fossilized coral. The lower Keys (from Little Duck Key in the east to the Dry Tortugas in the west) are oriented nearly parallel to the winds and trend nearly east-west. The lower Keys are composed of oolitic limestone, essentially preserved tidal-bar deposits.

Water depth is at a maximum in the middle Keys. As a result, the coral reef development is greatest in the shallower waters of the upper and lower Keys. Healthy coral reefs help stabilize islands like Garden Key. Core samples from United States Geological Survey monitoring wells reveal that the upper 3 feet of Garden Key consists of sand and other debris. The next 50 feet is Holocene limestone (less than 12,000 years old), including head coral and sand pockets; below that is Pleistocene (based on current scientific theory, between 12,000 and 2.5 million years old) Key Largo limestone. For the most part, the exposed surface of the key is sand, and therefore subject to weathering, tides, and waves.

SHIFTING SANDS

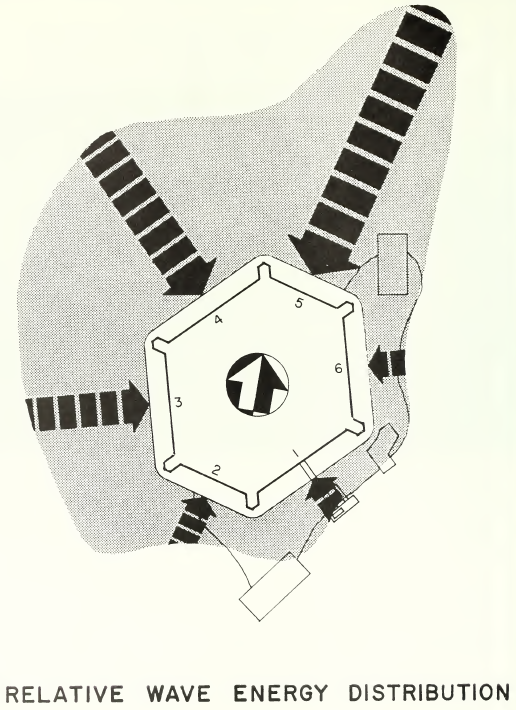

The prevailing ocean currents around the Dry Tortugas flow from east to west; prevailing winds, blowing from northeast to southwest, can also create waves and wind-formed currents, and these cooperate with the ocean currents. But the tidal current flows from north to south, against these other currents. This creates an overall arc in the Dry Tortugas, bowed toward the east. Storm surges play a large role in the shaping of the Dry Tortugas. All of these keys are within the 100 year floodplain (8 feet above sea level or lower). And, from June to November, tropical storms and hurricanes are not uncommon. Each year carries with it a 13% chance that a tropical storm or hurricane will hit Garden Key. Because so little of the Dry Tortugas are exposed, there is a constant risk that they can be washed away entirely.

Bird Key, once located just west of Garden Key, is now completely gone. Middle Key tends to disappear under the waves seasonally. And both Middle Key and East Key are in different positions than they were 100 years ago -- Middle Key has shifted about 300 yards to the southwest, and East Key has rotated 90 degrees and shifted about 500 meters south. Garden Key has been on the move throughout history. When Captain John Barnard was conducting a preliminary survey of the Dry Tortugas with an eye to building coastal fortifications, he consulted with local fishermen, who described how one of the keys had a permanent patch in the middle around 50 yards across, around which a larger area of sand migrated.

Lieutenant Horatio Wright, one of the first engineers who supervised the construction of Fort Jefferson, saw this migration effect firsthand. When Wright first arrived in November 1846, one of his first tasks was to ascertain the effects of the Great Havana Hurricane of 1846 (estimated to be at or near Category 5 strength), which had passed through a month prior. Wright noted that sand had migrated from the northern end of Garden Key to the southern end. At the head of the southernmost wharf on the key, where the water had been 7 to 8 feet deep, Wright found several feet of sand at all but high tide.

THE MOAT AND THE CHANNEL

Sand was a constant issue in the fort's moat. Engineers built a low wall, called a "counterscarp," around the outside of the fort. The counterscarp served two purposes. First, engineers wanted to keep the counterscarp above normal wave height, so that the walls and foundations of the fort would be protected from waves and current. Second, engineers wanted a 6 foot deep moat between the counterscarp and the fort, to keep attacking foot soldiers and ships from directly accessing the walls (and hiding from the cannons in the fort). For defensive purposes, it was important to keep the moat full of water. Openings were built into the counterscarp to keep the water at tide level and to keep the moat water from stagnating. (Since the fort's privies emptied into the moat, it was especially good to keep flushing out the moat!)

But the tide carried sand in with the water, especially to the southeast. The garrison had to continually work to keep sand and debris from clogging up the sluices and pipes in the walls. Today, you may see where sand is once again filling in the moat.

Although the subsequent construction of Fort Jefferson helped to stabilize Garden Key somewhat, the Dry Tortugas are still in motion. In 1856, a hurricane washed away half of neighboring Long Key and cut a channel through the remaining land. And although a deep channel was dredged between Bush Key and Garden Key in the early 20th century, later storms filled it in. During 2004, when Hurricane Charley passed over the Dry Tortugas, the land bridge connecting Bush Key to Garden Key washed over, but within a few hours the spit reformed.

LOGGING THIS EARTHCACHE

To log this earthcache, email us or send us a message and copy and paste these questions, along with your answers. Please do not post the answers in your log, even if encrypted. There's no need to wait for confirmation from us before you log, but we will email you back if you include your email address in the message.

1. The name of this earthcache: Shifting Sands of Garden Key.

2. From the cache coordinates, look out to the water. Describe the waves and current action here.

3. Go to the beach at Waypoint 2. Describe the waves and current action here. Can you notice a difference in the waves and current from the cache coordinates?

4. Check the moat at Waypoint 2. Is the self-flushing system working?

Photos of your visit are optional but always appreciated. Group answers are fine; just let us know who was with you.

SOURCES

Richard A. Davis, "Dry Tortugas National Park." Ann G. Harris et al, eds., Geology of National Parks Vol. 2 (2004).

Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, "Dry Tortugas National Park Geological Resource Management Issues Scoping Summary." Colorado State University Geologic Resource Evaluation (2005).

Edwin C. Bearss, "Historic Structure Report, Historic Data Section, Fort Jefferson: 1846-1898, Fort Jefferson National Monument, Monroe County, Florida." National Park Service (1983).

Louis Anderson, "Historical Structure Report, Architectural Data Section, Fort Jefferson National Monument, Florida." National Park Service (1988).

H.H.M. Bowman, "Botanical Ecology of the Dry Tortugas." Papers from the Tortugas Laboratory of the Carnegie Institute of Washington, Vol. XII (1918).

Elizabeth A. Pendleton et al., "Coastal Vulnerability Assessment of Dry Tortugas National Park to Sea-Level Rise." United States Geological Survey (2004).

Morgan Steinmetz, "Hurricane Charley Swamps Dry Tortugas and Fort Jefferson." Sarasota Herald-Tribune, Sept. 25, 2004.

NOAA tides and currents page for Garden Key, Dry Tortugas

This earthcache was placed with the permission of the National Park Service.