Ces Pâtis ou Landes sont parmi les dernières conservées de la région

C'est la seule Réserve Naturelle Nationale de la Marne (RNN #159)

These Pâtis or heathlands are among the preserved last of the area

It is the only National Nature reserve of the Marne (RNN #159)

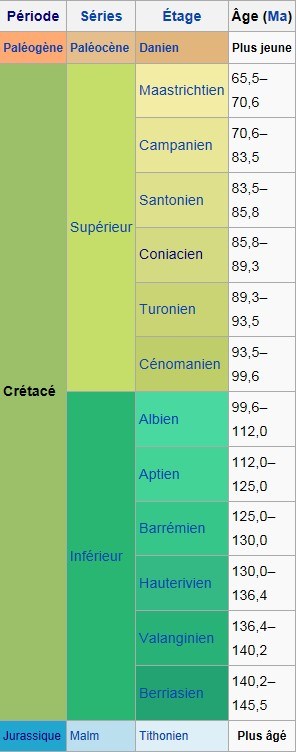

Le Crétacé

Le Crétacé

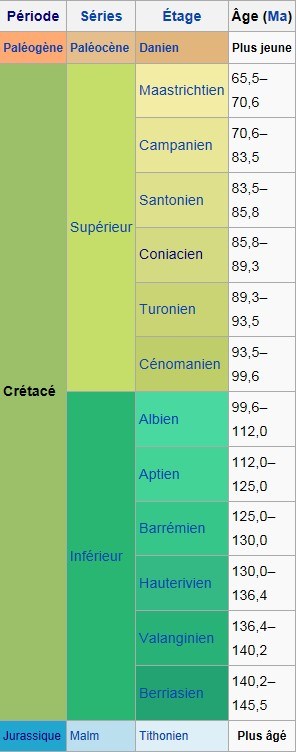

Le Crétacé est une période géologique qui s’étend de 145,5 ± 4 à 65,5 ± 0,3 Ma. Elle se termine avec la disparition des dinosaures et de nombreuses autres formes de vie. Cette période est la troisième et dernière de l’ère Mésozoïque; elle suit le Jurassique et précède le Paléogène.

Le Crétacé est une période géologique qui s’étend de 145,5 ± 4 à 65,5 ± 0,3 Ma. Elle se termine avec la disparition des dinosaures et de nombreuses autres formes de vie. Cette période est la troisième et dernière de l’ère Mésozoïque; elle suit le Jurassique et précède le Paléogène.

Sa fin est marquée par un stratotype riche en iridium que l’on pense associé à l’impact d’une météorite dans le Yucatan. Cette collision est considérée comme ayant participé fortement à l’extinction massive ayant entraîné entre autres la disparition des dinosaures. Néanmoins, la géologie montre que l'activité volcanique de grande ampleur commune aux cinq grandes extinctions avait déjà commencé avant l'arrivée du bolide.

Le Crétacé est nommé d’après le latin creta, «craie», se référant aux vastes dépôts crayeux marins datant de cette époque et que l’on a retrouvés en grande quantité en Europe. Il a été défini par Jean-Baptiste d'Omalius en 1822 d’après des couches stratigraphiques présentes dans le bassin parisien.

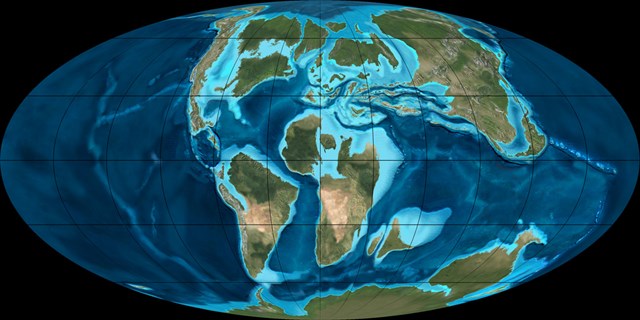

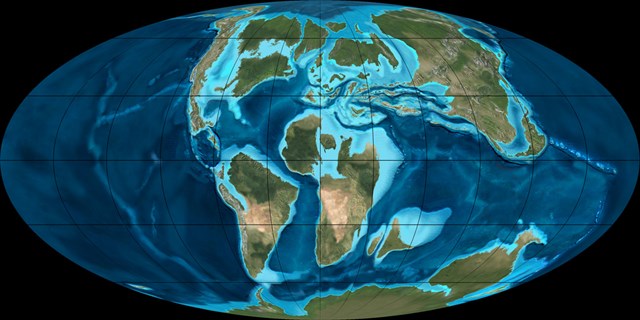

Durant le Crétacé, le supercontinent Pangée finit de se scinder pour former les continents actuels, bien que leurs positions soient encore substantiellement différentes de ce qu'elles sont de nos jours. L’océan Atlantique s’élargit alors que l’Amérique du Nord se dirige vers l’ouest ; dans le même temps le Gondwana, qui s’était auparavant détaché de la Pangée, se fracture en Antarctique, Amérique du Sud et Australie, et s’éloigne de l’Afrique. L’Inde et Madagascar restent rattachés à la plaque africaine au début du Crétacé ; l’Inde s’en détache vers la fin du Berriasien. L’océan Indien et l’Atlantique Sud apparaissent durant cette période.

Cette activité crée des chaînes de montagnes sous-marines le long des lignes de fractures, provoquant l’élévation du niveau de la mer dans le monde entier : c’est la crise magmatique du Crétacé supérieur, à l’origine des plateaux des Caraïbes, d’Otong-Java… Au nord de l’Afrique, la mer de Téthys continue de rétrécir. En Amérique du Nord une mer intérieure peu profonde se forme (Voie maritime intérieure de l'Ouest), puis commence à diminuer en laissant des dépôts marins minces intercalaires entre des couches de charbon. D’autres affleurements de cette période se situent en Europe et en Chine. Au maximum du niveau de la mer pendant le Crétacé, près d’un tiers des terres actuelles est submergé.

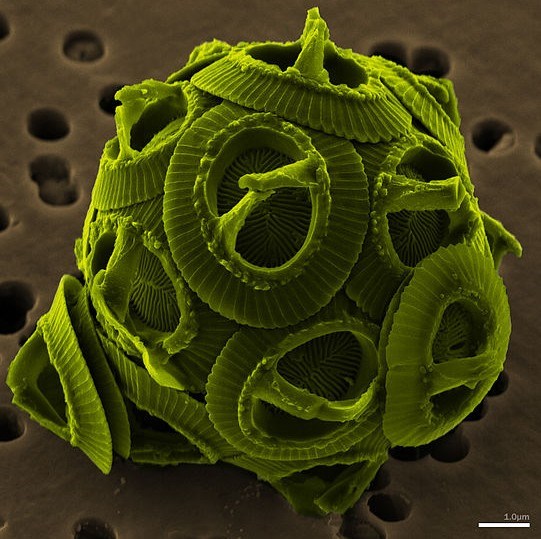

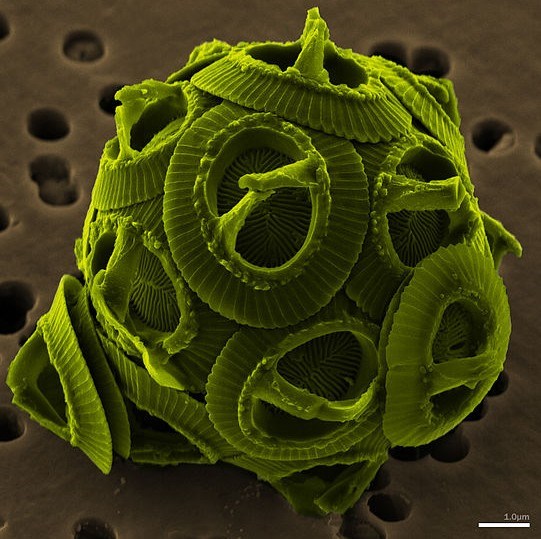

Le Crétacé est renommé pour ses formations calcaires : aucune autre période du Phanérozoïque n’en a produit autant. L’activité au niveau des dorsales océaniques enrichit les océans en calcium, permettant aux coccolithophoridés de s’approvisionner en cet élément.

La Craie

La Craie est une roche sédimentaire contenant presque exclusivement du carbonate de calcium CaCO3 et un peu d'argile. La craie est perméable, poreuse et friable.

La Craie est une roche sédimentaire contenant presque exclusivement du carbonate de calcium CaCO3 et un peu d'argile. La craie est perméable, poreuse et friable.

La craie s'est formée par accumulation de squelettes de micro-organismes marins, coccolithes essentiellement, à l'époque géologique du Crétacé auquel elle a donné son nom.

Les Coccolithophores sont des algues unicellulaires microscopiques. Elles protègent leur unique cellule sous une couche de plaques de calcite généralement discoïdes appelées coccolithes. Les coccolithophores pèlent continuellement toute leur vie et laissent donc tomber sur les fonds marins leurs coccolithes.

La forme de la plaque en pépin arrondi lui a donné son nom. Elle a entre un et une dizaine de micromètres de diamètre.

Bien que les coccolithes soient énergétiquement coûteux à produire, leur fonction n'est pas claire.

Voici plusieurs hypothèses :

- Défense contre le broutage par le zooplancton ou l'infection par les parasites

- Maintenance de la flottabilité,

- Evacuation du dioxyde de carbone pour la photosynthèse

- Filtration de la dangereuse lumière ultra-violette.

La Réserve

Le sous-sol est en grande partie composée de craie.

Cet ensemble forme une mosaïque de milieux d’un très grand intérêt floristique et faunistique, d’autant plus remarquable puisque situé en bordure d’un secteur consacré à l’agriculture intensive : la Champagne crayeuse.

Ils renferment une grande diversité de milieux naturels:

Des zones de landes plus ou moins relictuelles au sein de zones forestières.

Elles étaient utilisées pour le pacage des ovins et des bovins d’où le nom de «Pâtis» ou «Battis», et constituent aujourd’hui l’un des derniers témoins des pâtis du plateau tertiaire de la Brie champenoise. Ces formations végétales correspondent à des landes sub-atlantiques à Callune et Genêts, accompagnées de prairies à Molinie, de chênaies acidiphiles et de pinèdes claires à pins sylvestres et genévrier commun. Ces pins parfois rabougris évoquaient à Mr Bournérias (célèbre botaniste qui a redécouvert les pâtis en 1973) la forêt de pins à crochets des tourbières jurassiennes.

Un réseau important de mares, temporaires ou permanentes, qui se sont formées au sein des landes ou dans les parcelles plus forestières, suite à l’exploitation d’argile ou de meulière par les habitants. Il s’agit dans l’ensemble de mares oligotrophes.

Différents types de chênaies plus ou moins acidiphiles et hydromorphes. Les stations les plus hydromorphes sont caractérisées par la dominance de la Molinie dans la strate herbacée.

Une pelouse calcaire mésophile de type Mesobromion fortement envahie par le Brachypode penné, la Fructicée et la Pinède. La tempête de l’hiver 1999 a abattu de nombreux pins et permis la réouverture naturelle d’une grande partie de la pelouse.

Un marais alcalin de pente dominé par le Choin noirâtre et le Jonc à tépales obtus situé en fond de vallon et complètement enchâssée au cœur de la forêt. Le marais constitue la source d’un ruisselet rejoignant le Darcy Rau et présente des niveaux variés de tuff et de tourbe.

The Cretaceous

The Cretaceous

The Cretaceous is a geologic period and system from circa 145.5 ± 4 to 65.5 ± 0.3 million years (Ma) ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era. It is the last period of the Mesozoic Era, and, spanning 80 million years, the longest period of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The Cretaceous is a geologic period and system from circa 145.5 ± 4 to 65.5 ± 0.3 million years (Ma) ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era. It is the last period of the Mesozoic Era, and, spanning 80 million years, the longest period of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The Cretaceous was a period with a relatively warm climate, resulting in high eustatic sea levels and creating numerous shallow inland seas. These oceans and seas were populated with now extinct marine reptiles, ammonites and rudists, while dinosaurs continued to dominate on land. At the same time, new groups of mammals and birds, as well as flowering plants, appeared. The Cretaceous ended with a large mass extinction, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, in which many groups, including non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and large marine reptiles, died out. The end of the Cretaceous is defined by the K–Pg boundary, a geologic signature associated with the mass extinction which lies between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Eras.

The Cretaceous as a separate period was first defined by a Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822, using strata in the Paris Basin and named for the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate deposited by the shells of marine invertebrates, principally coccoliths), found in the upper Cretaceous of western Europe. The name Cretaceous was derived from Latin creta, meaning chalk. The name of the island Crete has the same origin.

During the Cretaceous, the late-Paleozoic-to-early-Mesozoic supercontinent of Pangaea completed its tectonic breakup into present day continents, although their positions were substantially different at the time. As the Atlantic Ocean widened, the convergent-margin orogenies that had begun during the Jurassic continued in the North American Cordillera, as the Nevadan orogeny was followed by the Sevier and Laramide orogenies.Though Gondwana was still intact in the beginning of the Cretaceous, it broke up as South America, Antarctica and Australia rifted away from Africa (though India and Madagascar remained attached to each other); thus, the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans were newly formed. Such active rifting lifted great undersea mountain chains along the welts, raising eustatic sea levels worldwide. To the north of Africa the Tethys Sea continued to narrow. Broad shallow seas advanced across central North America (the Western Interior Seaway) and Europe, then receded late in the period, leaving thick marine deposits sandwiched between coal beds. At the peak of the Cretaceous transgression, one-third of Earth's present land area was submerged.The Cretaceous is justly famous for its chalk; indeed, more chalk formed in the Cretaceous than in any other period in the Phanerozoic. Mid-ocean ridge activity—or rather, the circulation of seawater through the enlarged ridges—enriched the oceans in calcium; this made the oceans more saturated, as well as increased the bioavailability of the element for calcareous nanoplankton. These widespread carbonates and other sedimentary deposits make the Cretaceous rock record especially fine. Famous formations from North America include the rich marine fossils of Kansas's Smoky Hill Chalk Member and the terrestrial fauna of the late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. Other important Cretaceous exposures occur in Europe (e.g., the Weald) and China (the Yixian Formation). In the area that is now India, massive lava beds called the Deccan Traps were erupted in the very late Cretaceous and early Paleocene.

The Chalk

The Chalk is a soft, white, porous sedimentary rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite CaCO3. Chalk is composed mostly of calcium carbonate with minor amounts of silt and clay.

The Chalk is a soft, white, porous sedimentary rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite CaCO3. Chalk is composed mostly of calcium carbonate with minor amounts of silt and clay.

It forms under reasonably deep marine conditions from the gradual accumulation of minute calcite plates (coccoliths) shed from micro-organisms called coccolithophores.

The Chalk is a European stratigraphic unit deposited during the late Cretaceous Period.

Ninety million years ago the chalk downland of Northern Europe was ooze accumulating at the bottom of a great sea.

Protozoans such as foraminifera lived on the marine debris that showered down from the upper layers of the ocean.

Their shells were made of calcite extracted from the rich sea-water.

As they died a deep layer gradually built up and eventually, through the weight of overlying sediments, became consolidated into rock.

Later earth movements related to the formation of the Alps raised these former sea-floor deposits above sea level.

It is common to find chert or flint nodules embedded in chalk.

The Reserve

This Champagne region of France is mostly underlain by chalk deposits.

This unit forms a mosaic of mediums of a very great floristic and faunistic interest, all the more remarkable since located in edge of a sector devoted to the intensive farming: the Champagne chalky.

They contain a great diversity of natural environments:

Zones of moors, more or less relictuelles within forest zones.

They were used for the pasturage of the sheep and the cattle from where the name of “Suffered” or “Beat”, and constitute today one of the last witnesses of suffered from the tertiary plate of the Brie Champagne. These vegetable formations correspond to sub-Atlantic moors with Callune and Genêts, accompanied by meadows with Molinie, oak groves acidiphiles and clear pine forests with woodland pines and common juniper. These sometimes scraggy pines evoked with Mr. Bournérias (botanist celebrates who rediscovered suffered them in 1973) the forest of pines with hooks of the Jurassic peat bogs.

An important network of ponds, temporary or permanent, which were formed within the moors or in the forest pieces, following the exploitation of clay or grinding by the inhabitants. They are as a whole oligotrophic ponds.

Various types of oak groves more or less acidiphiles and hydromorphic. The most hydromorphic stations are characterized by the predominance of Molinie in the herbaceous layer.

A lawn calcairemésophile of the Mesobromion type strongly invaded by pennate Brachypode, Fructicée and the Pine forest. The storm of the winter 1999 cut down many pines and allowed the natural reopening of most of the lawn.

An alkaline marsh of slope dominated by Choin blackish and the blunt Snap ring with tepals located in bottom of small valley and completely enchased in the middle of the forest. The marsh constitutes the source of a little stream joining Darcy Rau and present varied levels of tuff and peat.

Avant de valider votre log, vous devez m'envoyer par mail vos réponses aux trois questions suivantes:

- Q1: De combien de sites distincts se compose cette RNN (1, 2, 3 ou 4) ?

- Q2: Etes-vous en face d'une pelouse Calcicole ou Silicicole ? Pourquoi ?

- Q3: Quelle est la longueur du rostre d'un Bélémnite ?

Une photo de vous et/ou de votre GPS devant le panneau d'informations serait appréciée (optionnel)

Before validationg your log, you must send me by mail your answers to the three following questions:

- Q1: How many distinct sites are included into this RNN (1, 2, 3 ou 4)?

- Q2: Are you in front of a Calcicole or Silicicole lawn? Why?

- Q3: What is the length of a Belemnite's rostrum?

A picture of you and/or your GPSr behind the informations panel will be appreciated (optionnal)