Intro

La Pared es un lugar interesante. No solo tiene un valor histórico, y deja a los visitantes impresionados por sus gigantescas olas y sus playas, también tiene una sorpresa geológica: Diques.

Cuanto más visitas Fuerteventura más interesante se vuelve. Ni en lo más mínimo por su interés geológico. También por este earthcache.

La Pared is an interesting place. Not only does it have a historical value, and not only are visitors blown away by the gigantic waves at its beach, it has also a geological surprise to show: dikes.

The more you visit Fuerteventura, the more the island becomes interesting. Not in the least because of its geological interest. Therefore this earthcache.

Diques - dikes

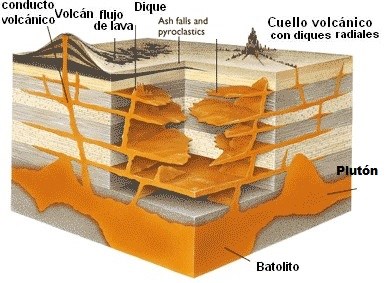

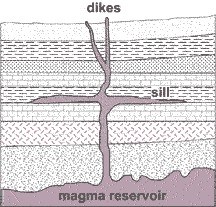

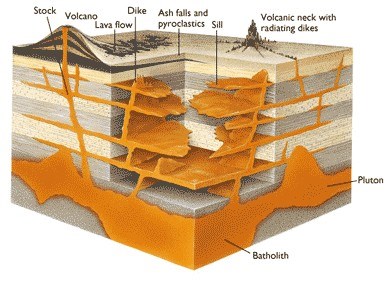

Un Dique, en geología, es una lámina de roca formada al resquebrajarse un bloque de roca preexistente. De todas formas, si la grieta se produce entre estratos de una roca estratificada, se denomina lámina o manto no dique (filón manto o sill).

Los Diques pueden ser de origen intrusivo o sedimentario. Cuando roca fundida se introduce en una grieta y cristaliza, es un Dique de tipo intrusivo, también llamado Dique magmático. Cuando sedimentos rellenan una grieta preexistente, es un Dique de tipo sedimentario.

Un Dique intrusivo o magmático, es un cuerpo ígneo con una muy alta relación de aspecto, lo que significa que su espesor es generalmente mucho menor que las otras dos dimensiones. El espesor puede variar desde una escala inferior a centímetros a superior a metros, y la longitud puede extenderse más allá de kilómetros. Los Diques muy delgados, a veces se denominan vetas.

Un Dique intrusivo o magmático, es un cuerpo ígneo con una muy alta relación de aspecto, lo que significa que su espesor es generalmente mucho menor que las otras dos dimensiones. El espesor puede variar desde una escala inferior a centímetros a superior a metros, y la longitud puede extenderse más allá de kilómetros. Los Diques muy delgados, a veces se denominan vetas.

Un Dique es una estrecha, estructura tabular de roca ígnea, que soporta a un lado otra capa preexistente de roca; esto implica que un Dique es siempre más reciente que la roca que lo contiene. Los Diques tienen generalmente un ángulo muy próximo a la vertical, pero posteriormente la deformación tectónica puede girar el orden del estrato a través del cual el Dique se propaga, de tal forma que el Dique puede llegar a quedar horizontal. Los próximos a la horizontal, o intrusiones adaptables, a lo largo del plano de la lámina entre capas, se denominan mantos intrusivos (intrusive sills).

Los Diques pueden tener importantes características geológicas en la superficie, como la dura roca fundida que no se erosiona tan rápido como el material que la envuelve.

A veces, los Diques aparecen en grupos, consistentes en varios cientos de Diques aparecidos más o menos en la misma fecha, durante un solo evento intrusivo.

Es coincidencia que el Dique en la formación de la pared de color amarillo, aparezca aquí y allí como una pared (imagen abajo).

A dike or dyke in geology is a sheet of rock that formed in a crack in a pre-existing rock body. However, when the crack is between the layers in a layered rock, it is called a sill, not a dike.

A dike or dyke in geology is a sheet of rock that formed in a crack in a pre-existing rock body. However, when the crack is between the layers in a layered rock, it is called a sill, not a dike.

Dikes can be either intrusive or sedimentary in origin. When molten rock intrudes into a crack then crystallizes, it is an intrusive dike, also called a magmatic dike. When sediment fills a pre-existing crack, it is a sedimentary dike.

An intrusive or magmatic dike is an igneous body with a very high aspect ratio, which means that its thickness is usually much smaller than the other two dimensions. Thickness can vary from sub-centimeter scale to many meters, and the length can extend over many kilometers. Very thin dikes, or dikelets, are sometimes called veins.

A dike is a narrow, tabular body of igneous rock, shouldering aside other pre-existing layers or bodies of rock; this implies that a dike is always younger than the rocks that contain it.

Dikes are usually high-angle to near-vertical in orientation, but subsequent tectonic deformation may rotate the sequence of strata through which the dike propagates so that the dike becomes horizontal.

Dikes are usually high-angle to near-vertical in orientation, but subsequent tectonic deformation may rotate the sequence of strata through which the dike propagates so that the dike becomes horizontal.

Near-horizontal, or conformable intrusions, along bedding planes between strata are called intrusive sills.

Dikes can be prominent geologic features at the surface, as the weathering of the hard igneous rock does not take place as fast as for the surrounding material.

Sometimes dikes appear in swarms, consisting of several to hundreds of dikes emplaced more or less contemporaneously during a single intrusive event.

It’s a coincidence that the dike with the yellow-coloured rock formation (picture below) looks here and there like a build wall.

Extra

(no es el objeto de este earthcache - not the subject of this earthcache)

Esta coincidencia nos dice algo de la historia de Fuerteventura. Aunque no es el objeto de este earthcache, es sin embargo digno de mencionar.

Fuerteventura, como el resto de las Islas Canarias, estuvo habitada por primitivos paganos antes de que fuera invadida por los europeos.

El análisis de restos prehistóricos parece indicar que esta gente llegó del Norte de Africa, confirmado por numerosas similitudes lingüísticas entre nombres de lugares y palabras prehispánicos, y el lenguaje de Los Bereberes del Norte de Africa.

Fuerteventura era conocida como Herbania, posiblemente en referencia a su rica vida vegetal en época antigua (aunque es difícil de creer ahora mirando su desértico paisaje) pero más probable de la palabra Bereber “bani” que significa muro. Un muro bajo que atraviesa a lo ancho la parte más estrecha de la isla desde La Pared hasta la costa Este, dividiéndola en dos reinos.

Maxorata en el norte era regida por Guiza, y Jandia en el sur regida por Ayoze. Aunque ostensiblemente regida por estos dos reyes, ellos por turnos seguían los consejos de una madre e hija sacerdotisas Tibiabin y Tamonante. Según las guías turísticas, aún quedan restos del muro, pero cuando preguntas, nadie está muy seguro de exactamente donde. Estos Diques no tienen ninguna relación con el muro que separaba el Norte del Sur. En 1404 Gadifer de La Salle, terrateniente de la arena negra volcánica de Ajuy en el lado occidental de Fuerteventura, con una fuerza mixta de soldados franceses y castellanos continuo la conquista de las islas Canarias que él y Jean de Bethancourt habían comenzado en 1402 en Lanzarote. A la vez que de La Salle desembarcaba, de Bethancourt estaba en España recibiendo el título de Señor de las Islas Canarias, otorgado por Enrique III de Castilla y transportando un mayor número de tropas que más tarde se unirían a de La Salle en Fuerteventura y fundando el primer asentamiento en un valle 10 km tierra adentro. Una ciudad que todavía lleva el nombre del primer aventurero, Betancuria.

Maxorata en el norte era regida por Guiza, y Jandia en el sur regida por Ayoze. Aunque ostensiblemente regida por estos dos reyes, ellos por turnos seguían los consejos de una madre e hija sacerdotisas Tibiabin y Tamonante. Según las guías turísticas, aún quedan restos del muro, pero cuando preguntas, nadie está muy seguro de exactamente donde. Estos Diques no tienen ninguna relación con el muro que separaba el Norte del Sur. En 1404 Gadifer de La Salle, terrateniente de la arena negra volcánica de Ajuy en el lado occidental de Fuerteventura, con una fuerza mixta de soldados franceses y castellanos continuo la conquista de las islas Canarias que él y Jean de Bethancourt habían comenzado en 1402 en Lanzarote. A la vez que de La Salle desembarcaba, de Bethancourt estaba en España recibiendo el título de Señor de las Islas Canarias, otorgado por Enrique III de Castilla y transportando un mayor número de tropas que más tarde se unirían a de La Salle en Fuerteventura y fundando el primer asentamiento en un valle 10 km tierra adentro. Una ciudad que todavía lleva el nombre del primer aventurero, Betancuria.

Así se creó la herencia española en la isla, con la influencia francesa reducida a unas pocas versiones castellanizadas de nombres de sitios franceses. Como Morro Jable, del francés “sable” que significa arena, La Oliva del olivo, y Betancuria la ciudad en el interior fundada por Jean de Bethancourt. Incluso el nombre de la isla se dice que es una versión de la exclamación de Bethancourt “Que forte aventure”.

En 1405 con la ayuda de la madre e hija sacerdotisas locales Tibiabin y Tamonante, de Bethancourt consiguió dirigir a los dos reyes oponentes, Ayoze de Maxorata y Guize de Jandia a su bautismo para convertirse al cristianismo y entregar la señoría a los Normandos a cambio de derechos territoriales y quedar libre de tributos durante nueve años.

This coincidence lead us to some history of Fuerteventura. Although it is not the subject of this earthcache, it is nevertheless interesting to mention.

Fuerteventura, like the rest of the Canary islands, was inhabited by primitive pagan people prior to its invasion by Europeans.

Analysis of prehistoric remains seem to indicate that this people arrived from North Africa, and this is borne out by many linguistic similarities between pre-hispanic place names, words and the language of the Berbers in North Africa.

Fuerteventura was known as Herbania, possibly a reference to its abundant plant-life in ancient times (though it is hard to believe now looking at its barren thirsty landscape) but more likely from the Berber word 'bani' meaning wall. A low wall spanned the narrowest width of the island, from La Pared (which means wall in Spanish) over to the east coast, dividing it into two kingdoms.

Maxorata in the North was ruled by Guize, and Jandia in the South was ruled by Ayoze. Although ostensibly ruled by these two kings, they in turn took advice and guidance from a mother and daughter team of two priestesses, Tibiabin and Tamonante.

According to the guidebooks segments of the wall still exist but when you ask about it nobody is quite sure where exactly. The dikes before you have definitely no relation with the wall separating the North and the South.

In 1404 Gadifer de La Salle landed on the black volcanic sand of Ajuy on the western side of Fuerteventura with a mixed force of French and Castillian soldiers to continue the conquest of the Canary Islands that he and Jean de Bethancourt had begun in 1402 in Lanzarote. At the time of de La Salle’s landing de Bethancourt was in Spain having the title Lord of the Canary Islands bestowed upon him by Henry III of Castile and trying to raise more troops but later joined de La Salle in Fueteventura and founded the first settlement in a valley about 10 km inland, a town that still bears the senior adventure’s name, Betancuria.

Thus the island’s Spanish heritage was created, with the French influence reduced to a few Castillianised versions of French place names such as Morro Jable (from the French ‘sable’ meaning sand), La Oliva (the olive tree) and Betancuria, the inland capital founded by Jean de Bethancourt. Indeed the island’s name itself is said to be a Spanish adaptation of Bethancourt’s exclamation ‘Que forte aventure!’

Thus the island’s Spanish heritage was created, with the French influence reduced to a few Castillianised versions of French place names such as Morro Jable (from the French ‘sable’ meaning sand), La Oliva (the olive tree) and Betancuria, the inland capital founded by Jean de Bethancourt. Indeed the island’s name itself is said to be a Spanish adaptation of Bethancourt’s exclamation ‘Que forte aventure!’

In 1405 with the help of the mother-daughter local priestesses Tibiabin and Tamonante de Bethancourt managed to get the two opposing kings at the time, Ayoze of the Maxoratas and Guize of the Jandia, to become baptised Christians, and surrender overlordship to the Norman in return for retaining land rights and exemption from tribute for nine years.

Tareas - Tasks

Aparca en el aparcamiento con las coordenadas ((N28 12.755 W014 13.256), elige la ruta comenzando en (N28 12.759 W014 13.300); cuando llegues a (N28 12.671 W014 13.493) coge a tu derecha un pequeño camino hacia la playa. En las coordenadas del earthcache no solo estas mirando al Oceano Atlántico sino que lo sientes y suena como si estuvieras en medio de él.

En estas coordenadas también puedes ver claramente e incluso tocar, un fenómeno que se ve en sitios volcánicos: Diques. Los diques forman un grupo radial.

Debes realizar las siguientes tareas para registrar este cache con éxito:

- ¿Cuántos diques ves desde aquí , más de cinco o menos?

- ¿Cuál es el espesor estimado de los Diques?

- Describe brevemente la formación de los Diques

- Opcional: Una foto de esta esquina de la playa de La Pared con sus olas arrolladoras, adjúntala en tu registro, sería de agradecer.

Puedes enviar tu respuesta a jolanaran@gmail.com y registrar el cache a la vez. Cuando la respuesta (breve) no sea correcta, tu registro será eliminado y te informaremos.

Park at the parking coordinates (N28 12.755 W014 13.256), choose the trail starting at (N28 12.759 W014 13.300); when arriving at (N28 12.671 W014 13.493) choose on your right side a small path to the beach.

At the given coordinates of the earthcache you are not only looking at the Atlantic Ocean, but it feels and sounds as you are in the middle of it.

At these coordinates you can also clearly see, and even touch, a phenomenon that can be seen on volcanic places: dikes. The dikes form part of a radial swarm.

The following tasks are required to log this cache successfully:

- How many dikes do you see from this place: more than 5 or less than 5?

- What’s the estimated thickness of the dikes at this place?

- Describe short how dikes are formed

- Optional: a photo of this corner of La Pared beach with its overwhelming waves, attached to your log, would be appreciated.

You can send your answers to jolanaran@gmail.com and you can log at the same time. When the (easy) answers are not correct or are missing, your log will be removed, and you will be informed.

Answers in German or French are also accepted, I will be able to understand