Localización

La singularidad y tamaño del Diapiro pozano lo convierten en uno de los atractivos naturales más importantes no solo de la villa salinera sino de toda la provincia pese a lo cual aún es poco conocido. Esto es así ya que se trata de la mayor formación diapirica de todo el continente europeo a lo que se añade la facilidad de acceder a esta singularidad geológica por los interesados. Recordar que el origen de la explotación de la sal está precisamente en este diapiro, que al tiempo permite conocer el origen geológico de toda la comarca.

Actualmente el Diapiro de Poza de la Sal está protegido a través de la declaración de Bien de Interés Cultural con la categoría de Sitio Histórico del territorio salinero ubicado en su fondo. Los límites aprobados para la protección y conservación del Salero incluyen toda la estructura diapírica.

Geomorfologia

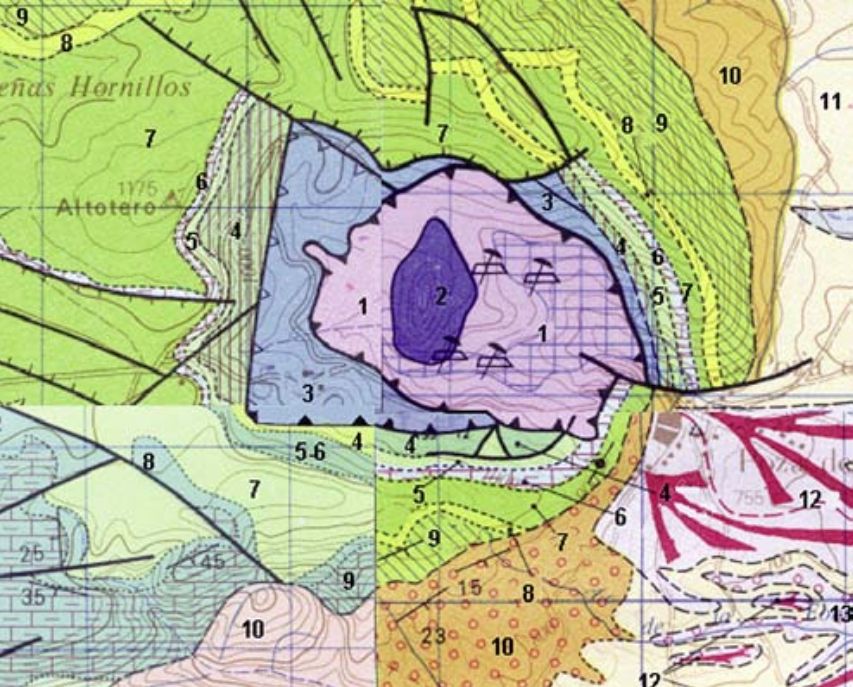

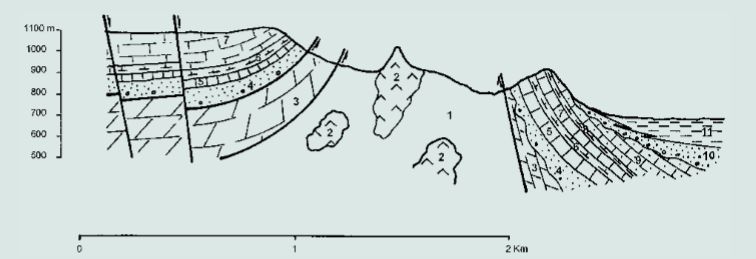

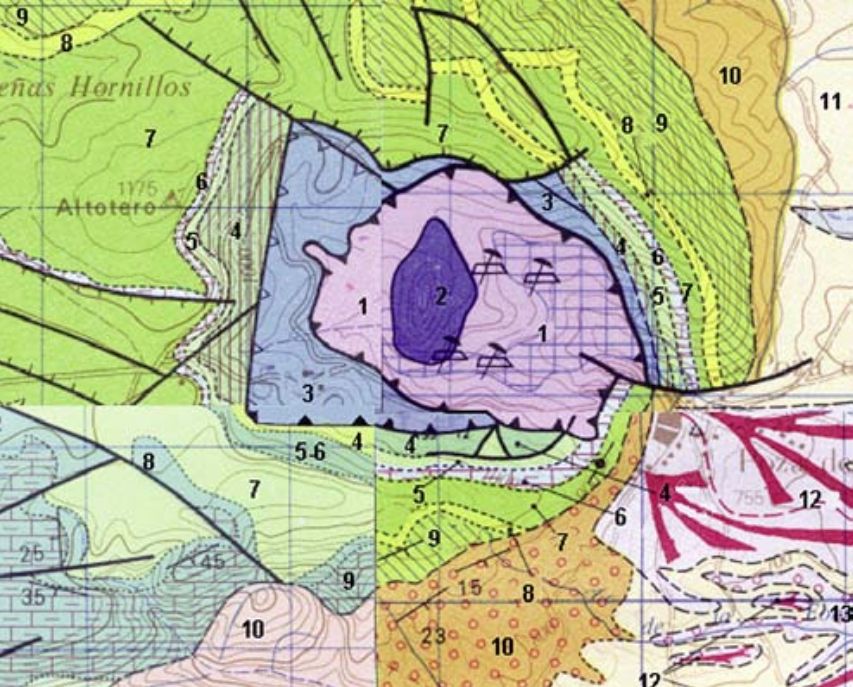

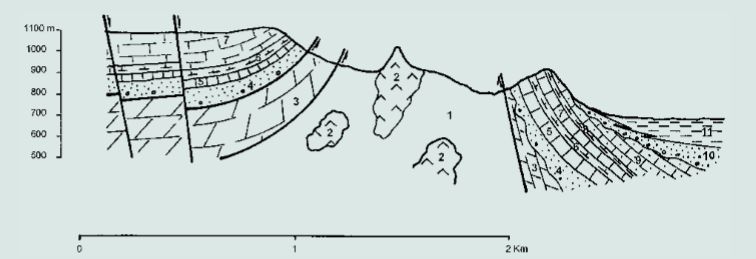

Rodeado por las calizas del Cretácico Superior, en un paisaje dominado por las extensas altiplanicies de los páramos, y los rellenos terciarios de la Depresión de La Bureba, el diapiro de Poza constituye un punto neurálgico de indudable interés geotectónico. Se trata de una de las estructuras más claras de diapirismo triásico.

1– Arcillas y margas abigarradas, yesos y sal. Keuper, TRIÁSICO SUP. (–230/–210 m.a.)

2– Ofitas. Keuper, TRIÁSICO (–230/–210 m.a.)

3– Carniolas, calizas, calizas margosas y margas. Rethiense-Dogger, TRIÁSICO-JURÁSICO (–210/–150 m.a.)

4– Arenas, arenas conglomeráticas, conglomerados y arcillas carbonosas. F. Utrillas. Albiense Med.-Cenomaniense Inf., CRETÁCICO (–107/–91 m.a.)

5– Calcarenitas con Orbitolinas y/o Praealveolinas, margas, calizas con Exogira, areniscas y dolomías. Cenomaniense Inf.-Sup., CRETÁCICO SUP. (–91 m.a.)

6– Calizas arcillosas nodulosas, calizas y margas calcáreas gris-verdosas. Turoniense Inf., CRETÁCICO SUP. (–90 m.a.)

7– Calizas, calizas dolomíticas, dolomías, calcarenitas y margas. Turoniense Inf.Santoniense Inf., CRETÁCICO SUP. (–90/–85 m.a.)

8– Margas hojosas grises y amarillentas, margas calcáreas y calizas nodulosas. Lacazinas a techo. Coniaciense-Santoniense Med., CRETÁCICO SUP. (–88/–85 m.a.)

9– Calizas, dolomías y calcarenitas bioclásticas, localmente nodulosas, con Lacazinas y Miliólidos. Santoniense Med.-Sup., CRETÁCICO SUP. (–85/–83 m.a.)

10– Conglomerados calcáreos marginales y arcillas rojas. F. Bureba. OLIGOCENO-MIOCENO INF. (–34/–15 m.a.)

11– Arcillas Rojas con canales de arenas, areniscas y conglomerados. F. Bureba. AgenienseOrleaniense, MIOCENO INF. (–23/–15 m.a.)

12– Gravas calcáreas, arenas y arcillas. Glacis. PLEISTOCENO (–1,8/–0,01 m.a.). 13. – Gravas poligénicas, arenas y limos. PLEISTOCENO (–1,8/–0,01 m.a.). |

Historia geológica

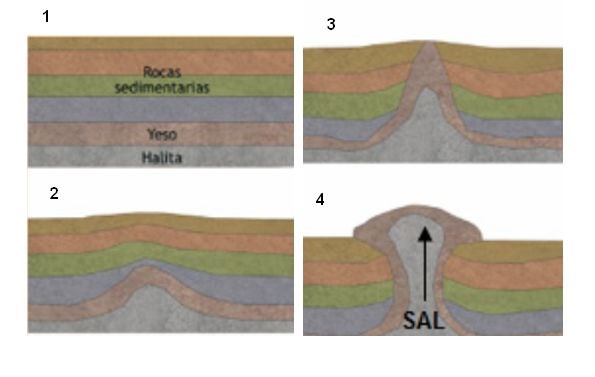

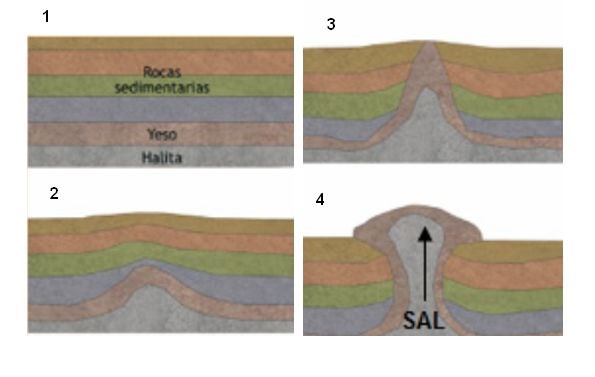

Hace más de 200 millones de años (Triásico), gran parte de lo que hoy es la Cuenca Cantábrica configuraba los fondos de un mar del pasado de la Tierra que llamamos Mar de Thetys. Por distintos fenómenos, probablemente una subida general de la temperatura que fundiera parte de los hielos polares, las aguas subieron de nivel invadiendo nuevas zonas, que quedaron convertidas en un mar costero de poca profundidad, o tal vez en un lago continental de elevada salinidad. En el fondo de esta cuenca somera fueron sedimentándose materiales procedentes de los ríos que desembocaban en su orilla, acumulándose arcillas, yeso y sal. La climatología era desértica con pocas aportaciones fluviales, que no compensarían las fuertes pérdidas por evaporación, aumentando así la concentración salina del agua e iniciándose la precipitación. Simultáneamente se produce la efusión de materiales volcánicos de magmatismo básico (ofitas), que indica un proceso distensivo de adelgazamiento de la corteza. Estos materiales volcánicos, en unos casos salieron al exterior a través de los sedimentos, produciendo erupciones submarinas, y en otros quedaron incluidos entre los estratos salinos y arcillosos, llegando a enfriarse sin haber alcanzado la superficie. Esta época del Triásico, el Keuper, duró alrededor de 10 millones de años, y los estratos de sedimento llegaron, a formar un acúmulo de 400 ó 500 m. de espesor. Los geólogos deducen, por la diferente composición de las rocas, que a finales del Triásico las condiciones ambientales parecen haberse modificado, pues hay menos aportes arcillosos y más materiales carbonatados, lo que supone un hundimiento general del fondo de la cuenca, que favorece la invasión marina, y durante todo el Jurásico y el Cretácico fueron sedimentándose nuevos materiales que cubrieron a los del Keuper, aumentando así el grosor de la capa que encerraba la sal.

Finalizando el Cretácico se inicia una paulatina regresión hacia el régimen continental, que da lugar a la existencia de amplias zonas emergidas. Al final del período Eoceno, hace unos 40 millones de años, comienzan a formarse la sierra de Cantabria y los montes Obarenes, levantándose también con ellos los materiales del Páramo, y quedando formadas unas cubetas o planicies más bajas, como es el caso de la llanura Burebana, donde se produce una sedimentación continental. La formación del diapiro comienza al final del período Jurásico, cuando ya los materiales sedimentados sobre la sal y la arcilla del Keuper alcanzaban un espesor considerable, produciéndose los primeros movimientos halocinéticos, es decir, movimientos ascendentes de la sal, debidos a la menor densidad de esta (2,1 gr/cm.3) con relación a la de los materiales envolventes, de 2,5 a 2,7 gr/cm.3. Los movimientos halocinéticos siguieron ejerciéndose, desde su inicio, durante todo el Cretácico, mientras continuaba engrosándose la cubierta, por la incesante sedimentación de calizas marinas que ocurría en superficie. Ya en la era Terciaria, levantado el Páramo, el domo o masa salina ascendente debió encontrar en el anticlinal llamado de Villalta, la zona más propicia para romper la cubierta, haciéndolo en la curvatura que el eje de aquel toma hacia la Cuenca del Duero, y provocando en dichas capas un cuarteamiento en cuatro sectores principales, dando lugar a multitud de fallas radiales y concéntricas. Como resultado de esta ascensión, los materiales del Keuper, que podrían haber permanecido enterrados a unos 800 m. de profundidad bajo la superficie actual, aparecieron en el exterior. Sin embargo, esta ascensión cesó apenas rota la cubierta, según Hempel, por no haber suficiente masa salina. Esto ocurría en el Mioceno, hace entre 1 y 16 millones de años.

Para logar este EarthCache, envíame un mensage o correo electrónico con las respuestas a las siguientes preguntas:

1) ¿Que tipo de roca forma la parte elevada del diapiro? ¿Dame su altura estimada?

2) ¿Cuando comienza la elevación del diapiro?¿Cual fue la causa que causo dicha elevación?

3) Según el panel inforativo, ¿De que época es el terreno en que se encuentra ahora? ¿Cuantos metros atraveso el diapiro para alcanzar la superficie?

4) Añade una fotografia tuya en el local, u otra en la que se pueda ver algún objeto, o tu nick en un papel

-Si crees que as concluido con exito los objetivos de este Earth Cache, y me ha enviado todas las respuestas solicitadas, puede hacer el log. Luego yo comprobaré que son correctas, y si hay cualquier problema me pondre en contacto para arreglarlo.

-Logs sin respuestas enviadas previamente, seran borrados sin aviso

English (GoogleTranslate)

Location

The uniqueness and size pool Diapir not make it one of the most important natural attractions not only of the salt village but across the province in spite of which is still poorly understood. This is so because it is the largest diapiric training throughout the European continent to the ease of access to this geological uniqueness by stakeholders is added. Remember that the origin of the exploitation of the salt is precisely this diapiro that time allows to know the geological origin of the whole region.

Currently the Diapir Poza de la Sal is protected by the declaration of Cultural Interest with the category of Historical Site salinero territory located at the bottom. The limits approved for the protection and conservation of Salero include all diapiric structure

Geomorfology

Surrounded by the limestone of the Upper Cretaceous, in a market dominated by the extensive uplands moorland landscape, and tertiary inserts Depression of Bureba, the diapir Poza is a focal point of geotectonic undoubted interest. This is one of the clearest Diapirism Triassic structures.

1- Variegated clays and loams, gypsum and salt. Keuper Triassic SUP. (-230 / -210 A.m.)

2- Ofitas. Keuper Triassic (-230 / -210 a.m.)

3- Carniolas, limestone, marl limestone and marl. Rethiense-Dogger, Triassic-Jurassic (-210 / -150 a.m.)

4- Arenas, conglomeratic sands, conglomerates and carbonaceous clays. F. Utrillas. Albian-Cenomanian Med. Inf. Cretaceous (-107 / -91 a.m.)

5- Calcarenitas with Orbitolinas and / or Praealveolinas, marl, Exogira limestones, sandstones and dolomites. Inf. Cenomanian-Sup., Upper Cretaceous. (-91 A.m.)

6- nodular argillaceous limestone, limestone and calcareous marl gray-green. Turonian Inf., Upper Cretaceous. (-90 A.m.)

7- Limestone, dolomitic limestone, dolomite, calcarenite and marl. Turonian Inf.Santoniense Inf., Upper Cretaceous. (-90 / -85 A.m.)

8- leafy Margas yellowish gray, nodular limestone and calcareous marl. Lacazinas to ceiling. Coniacian-Santonian Med., Upper Cretaceous. (-88 / -85 A.m.)

9- limestones, dolomites and bioclastic calcarenite locally nodular with Lacazinas and miliolids. Santonian Med.-Sup., Upper Cretaceous. (-85 / -83 A.m.)

10- marginal calcareous conglomerates and red clays. F. Bureba. Oligo-Miocene INF. (-34 / -15 A.m.)

11- Red Clays channels sands, sandstones and conglomerates. F. Bureba. AgenienseOrleaniense, MIOCENE INF. (-23 / -15 A.m.)

12- calcareous gravels, sands and clays. Glacis. PLEISTOCENE (-1.8 / -0.01 a.m.). 13. - polygenic gravel, sand and silt. PLEISTOCENE (-1.8 / -0.01 a.m.). |

Geological History

More than 200 million years ago (Triassic), much of what is now the Cantabrian Basin configured funds past a sea of Earth we call Sea Thetys ago. For various phenomena, probably a general rise in temperature melt of polar ice, the waters rose level invading new areas, which were turned into a coastal shallow sea, or perhaps in a continental lake of high salinity. At the bottom of this shallow basin were sedimentándose materials from the rivers flowing into your bank, building up clay, gypsum and salt. The weather was desert with few fluvial deposits, which would not compensate the losses generated by evaporation, thus increasing the salinity of the water and beginning precipitation. Simultaneously the outpouring of volcanic material basic magmatism (Ophites), indicating an extensional process crustal thinning occurs. These volcanic materials, in some cases went outside through the sediments, producing underwater eruptions, and others were included between saline and clayey strata, and cooled without reaching the surface. This time of the Triassic, the Keuper, lasted about 10 million years, and the layers of sediment came to be an accumulation of 400 or 500 m. of thickness. Geologists deducted by the different composition of the rocks, which the late Triassic environmental conditions appear to have changed, as there are less clayey contributions and carbonate materials, which is a general collapse of the bottom of the basin, which favors the invasion marina, and throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous were sedimentándose new materials covering the Keuper, increasing the thickness of the layer which contained salt.

Completing the Cretaceous begins a gradual regression to the continental system, which leads to the existence of large areas emerged. At the end of the Eocene epoch, about 40 million years ago, they begin to form the Sierra de Cantabria and Obarenes mountains, also rising with them Páramo materials, and being formed cuvettes or lower plains, such as the Burebana plain, where a continental sedimentation occurs. Formation diapiro begins at the end of the Jurassic period, when the material sedimented on salt and clay Keuper reached a considerable thickness, producing the first halocinéticos movements, namely upward movement of salt due to the lower density of this (2.1 g / cm.3) in relation to the surround material, 2.5 to 2.7 g / cm.3. Halocinéticos followed the movements exerted from the beginning, throughout the Cretaceous, while continuing to thicken the deck, by the relentless deposition of marine limestone was happening on the surface. Already in the Tertiary, raised the Desert, the dome or salt dough up must have found in the anticlinal call Villalta, the area more conducive to breaking the cover, making the curvature axis that takes to the Cuenca del Duero, and causing cracking in these layers one on four main sectors, leading to a multitude of radial and concentric faults. As a result of this ascent, the Keuper materials that could have been buried about 800 m. deep below the present surface, they appeared abroad. However, this rise stopped just broken cover, according to Hempel, having not enough salt dough. This occurred in the Miocene, made between 1 and 16 million years.

To log this earthcache, send me an email or message with the answer to the following questions:

1) What type of rock forms the diapir´s highest part ? Give me their estimated height ?

2) When the rise diapiro begin? What caused the rise?

3) See the info panel: In that era was created the land under you ? How many meters crossed the diapir to reach the surface?

4) Add a photo of yourself at the place, or another in which you can see an object, or your nick on a piece of paper

-If you believe you have successfully completed this Earth Cache goals and has alreadysent to me all the requirements as requested, Please, feel free to log it as found. Later i will verify the requirements sent and, if necessary, contact you in order to make the necessary corrections to your log.

-Logs without answers, will be deleted without notice.