ABSTRACT

Kinshasa City, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is a case of an aborted urban development. Natural phenomena combined with political instability, collapse of state, and civil strife blurred further the inherited infantile urban character of colonial times to yield an urban morphogenetic crisis. In this article, we use surface and subsurfacegeological data in the form of several geological and hydrogeological maps, groundwater contour maps, geotechnical isopach and isohypse maps, and other illustrations that aid in the recognition of problems of pollution, accelerated erosion, and floods to highlight the geological constraints on sustainable urban planning, socio-urban setting, and human well being in this African megacity.

INTRODUCTION

General Statement

Geological conditions of the terrain and finite earth resources are key factors in urban sustainability of all large cities. However, direct experience in many developing countries shows that geological information is not appropriately considered in urban planning. In this article, we highlight the role of geologic knowledge in sustainable urbanism. Urban development of Kinshasa City has certain characteristic features.

- The city lacks long urban development. Over a time span of merely one century, the city developed from a rural-tribal sparse society into an ill-managed megacity. The limited preindependence urbanization features degraded and were replaced by chaotic growth because of political instability, collapse of state, and civil strife.

-

The steady rural exodus acted as a social diluting agent to the fragile and young preindependence urban social fabric. It is an observable phenomenon in Kinshasa that rural and urban characters intermingle and form a single social field or organization. Town and village form a well-recognized dichotomy. Slums, disconnected from any economic growth, encroached on the city. This explains the difficulty of applying classical urban theories and procedures to Kinshasa City (see, e.g., De Boeck, 2006).

Although the physical conditions of urban geology seem, at first sight, independent of these chaotic sociopolitical conditions, they do bear the effects through the deterioration of the geoenvironment and exhaustion of natural resources. The purpose of this contribution is to present an overview of the existing geoscience knowledge on Kinshasa City applicable to future urban planning and environmental protection. This introductory geological work provides, hopefully, indicators for planners, engineers, environmentalists, and decision makers to tackle the encroaching urgent issues of impaired water quality, soil erosion susceptibility, and floods. This work also offers methodologies and approaches that serve as prototypes for future urban research in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The study uses surface and subsurface geological data that have been obtained by many geologists during the20th century. Early data sets embody some inadequacies and ambiguities that should be considered as one goes through the results of this work.

Location

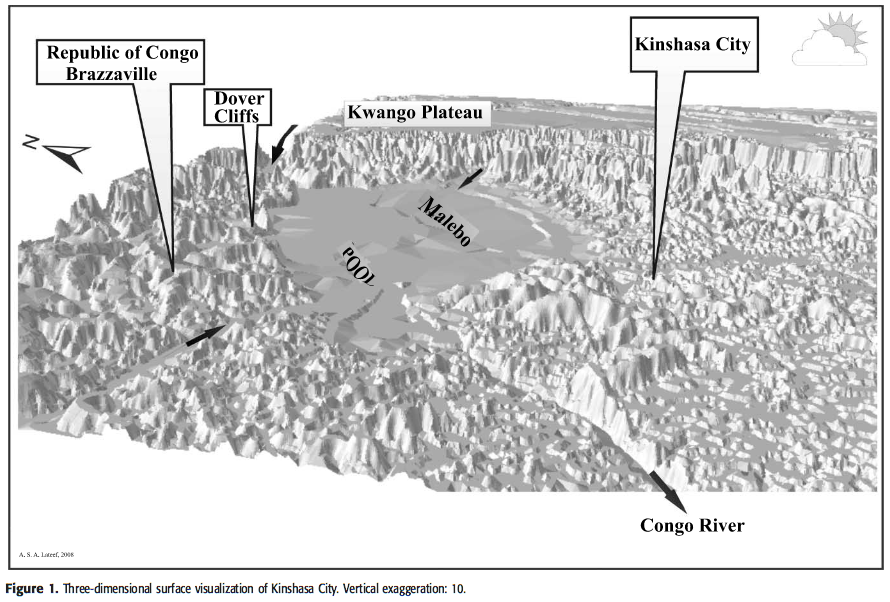

Kinshasa City is located on the left bank of the Congo River where the watercourse draws a wide crescent-circular pool: the Malebo Pool (Figure 1). The city lies between 4°17′ 30′′ and 4°30′ 00′′ latitude south and 15°12′ and 15°30′ longitude east. It is bound north and west by the Congo River, which is also the border with the Popular Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), east and northeast by the Bandundu Province, and south by the Bas Congo Province.

Brief History of the City

Archaeological findings indicate early man (late Acheulian and lower Paleolithic) presence in the Kinshasa plain (van Moorsel, 1968). During the last few centuries, the locality was part of the Kongo Kingdom. In the 19th century, the site was inhabited by natives living in large fishing and trading villages. One of these villages had the name Kinshasa. Later in that century, the navigation of the Congo River by Henry M. Stanley in 1877 led to the establishment of an inland trading river port in December 1881. The post was named Léopoldville, after the name of the King of Belgium. At the time of its foundation, Léopoldville occupied the present-day Mont Ngaliema as an almost western mirror image of Kinshasa Village. In 1885, the Berlin Conference acknowledged the Belgian royal role in the Congo, giving rise to the Congo Free State. The presence of rapids or cataracts between the mouth of the Congo River on the Atlantic and the newly established trading post made the river innavigable. This feature of the Congo River course handicapped transportation to and from Léopoldville. The construction of the Matadi railroad in 1889 – 1898 under the direction of General Albert Thys with native and expatriate manpower overcame this obstacle. This important event led eventually to the transformation of the small Léopoldville trading post into a city. In 1923, Léopoldville replaced the seaside town of Boma as the capital of the Belgian Congo. The name Léopoldville remained in use from 1881 to 1966. After that, the capital took the current name Kinshasa.

(...)

URBAN GEOLOGY

(...)

Geomorphological Setting

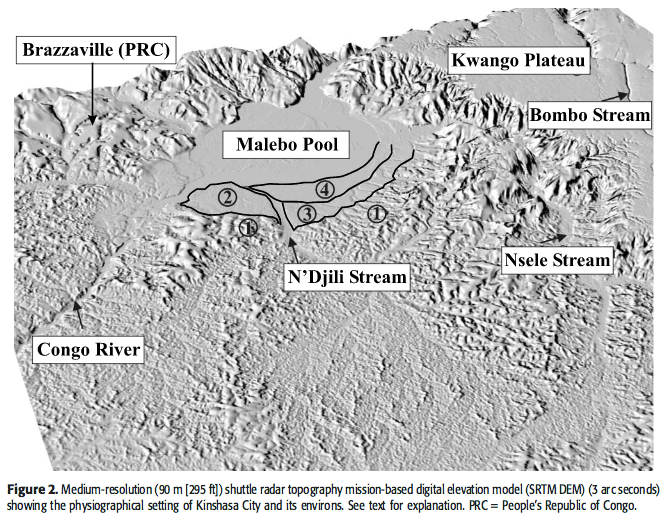

The city is located on the Malebo Pool. This pool has a circular, although slightly asymmetrical, form where the Congo River (water level at ∼298 m [978 ft] above sea level [a.s.l.]) broadens into an internal lake having a di- ameter of approximately 25 km (15 mi). On the southern bank of the pool, where Kinshasa City is located, the altitude of the city plain ranges between 300 and 350 m (984 and 1148 ft). Four macrogeomorphologic zones can be recognized in the Kinshasa City region: (1) the southern hills zone, (2) the gently undulating plain of Kinshasa City proper, (3) the eastern plain, and (4) the flood basin. These zones are depicted in Figure 2. East of Kinshasa City proper, the Kwango Plateau stands very distinct as a table-land. The indicated geomorphologic zones are bounded from the east by the prominent Kwango Plateau (∼700 m [2296 ft]) and from the west by gentle slopes that lead first to an altitude of 500 m (1640 ft) then to the vast plateau of cataracts or rapids (600 to 800 m [1968 to 2625 ft]). On the south, above the steep slopes, the hill zone shows a progressive increase of relief from 350 to 500 m (1148 to 1640 ft). On a larger scale, the landscape of the city also reflects small-scale geomorphologic phenomena and microrelief features that are beyond the scope of this article.

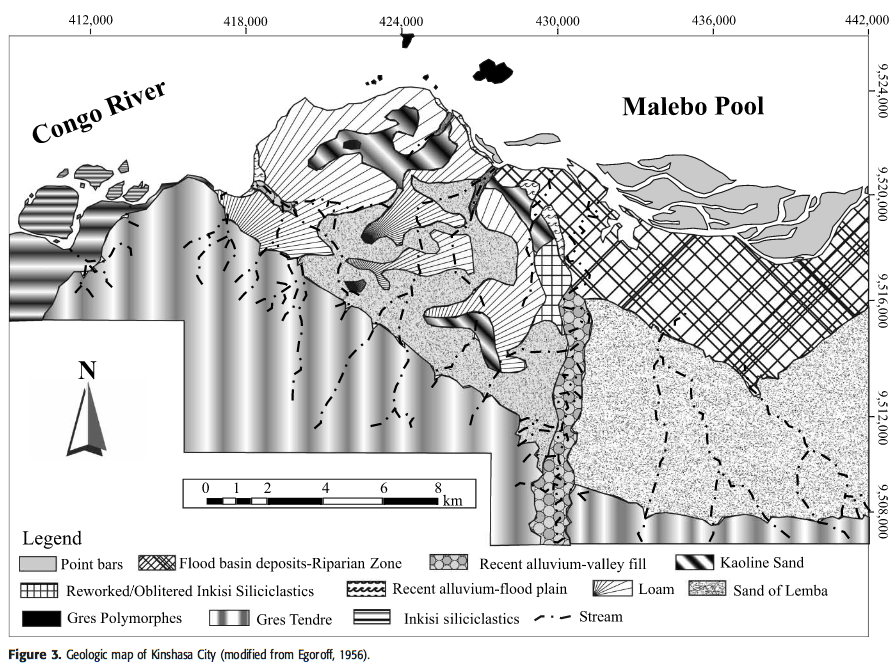

Geological Setting

The Kinshasa region is located on the eastern fringe of the Pan-African west Congo belt. Based on the geologi- cal reconstructions of Tack et al. (2001) and Frimmel et al. (2006), it appears that from a tectonostratigraphic point of view, the Kinshasa region is part of a foreland basin that postdates the Pan-African orogeny. The few folds and faulted folds (Schisto-Calcaire sequence) south-southwest of the Kinshasa Province (e.g., Bamba Kilenda locality) plunge, in the Kinshasa region, beneath undeformed gently northeast-dipping Inkisi siliciclastics and overlaying younger continental sediments. The geological setting of Kinshasa City has devel- oped in a transitional area between two geologically contrasting domains:

- To the west, down Mount Ngaliema and farther downstream the pool, subhorizontal, gently northeast-dipping red bed facies siliciclastic sedimentary rocks of the Inkisi Group (Frimmel et al., 2006), known as the Kinsuka arkoses, start outcropping and impose the first rapids or cataracts to the Congo River. From there, the river flows in a southwest-trending, approximately 500-m (1640-ft)-wide gorge, cut in the Inkisi red beds. The rocks display a prominent, subvertical, conjugate northeast- and northwest-trending jointing. They are unconformably overlain by generally poorly consolidated, although in places cemented, Upper Cretaceous sandstones, Kwango series (Ladmirant, 1964; Lepersonne, 1974), forming a range of rather flat-topped hills (∼500 m [1640 ft]), with gently graded interstream tracts and broad inactive valley floors (De Ploey, 1968; Van Caillie, 1987).

- To the east, near the locality of Maluku and upstream of the pool, the exposed section consists (from the bottom to the top) of Cretaceous white sands (Kwango series), commonly consolidated and forming along the northeasternmost part of the pool, the so-called Dover Cliffs (Dadet, 1966). These sandstones are over- lain by the Cenozoic Kalahari sequences, including Paleogene sands, locally strongly silicified into slabs of orthoquartzites (Grès Polymorphes), covered by Neogene loose sands (Sables Ocre). The latter form the flat, approximately 700-m (2296-ft)-high Kwango Plateau displaying an outstanding microrelief.

The general geological setting of the city is shown in Figure 3. For more regional geological features, the reader is referred to the Léopoldville quadrangle map.

(...)

Water Resources

General Statement

With abundant rainfall and the presence of the Congo River and tributary streams, Kinshasa City has plenty of water resources. However, the availability of safe drinking water is a challenge to the population. This paradoxical situation is clearly illustrated by Mwacan and Trefon’s (2004) statement that the water in Kinshasa is rare like it is in the Sahara. Insufficient water supply for the Kinois family has serious health consequences and adds a heavy burden on women who are responsible of the family affairs (J. Mukenyikalala, 2007, personal communication). Because of this shortage in water supply, it is not unusual to see women and men carrying large vats of water to their homes. The spatial growth of the city without a parallel development of treatment and distribution infrastructure made these inadequacies more apparent and more annoying in the everyday life of the citizens. At times, in the past, the authorities tried to use trucks and tankers to distribute drinking water in areas where the water distribution network does not exist but this, also, did not continue because of financial and maintenance obstacles. Until today, potable water production is based on surface water resources, river, and streams. The sole organ responsible for the distribution of drinking water in Kinshasa City is the “Régie des Eaux” or better known as “REGIDESO.” Up to 1960, the REGIDESO was doing satisfactorily. The situation started to deteriorate after 1960. Currently, the REGIDESO has three installations: one on the N’Djili stream, another on the Lukunga stream, and the third on the Congo River. The availability of surface waters did not call for effective exploitation of groundwater resources. Insufficiency of production and lack of distribution networks in many parts of the city, particularly in the peripheral communes, should bring attention to groundwater resources. (...)

Hydrogeology of Kinshasa City

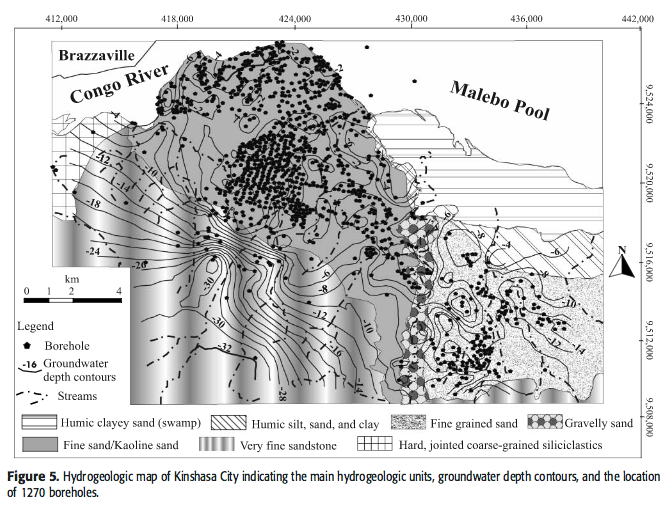

The hydrogeology of Kinshasa city is mostly that of an unconfined aquifer system hosted mostly in the unconsolidated sediment cover. In such a system, environmental issues are of great concern. The shallow water-table aquifer interacts and communicates with both the deeper free aquifers and with human activities and water bodies on the surface (streams, Congo River, and swamps). Therefore, a study of the shallow aquifer is not only important for water harvesting but also for antipollution and sanitation policies. The hydrogeologic map of Kinshasa (Figure 5) was compiled incorporating borehole location data of Van Caillie (1977 – 1978).

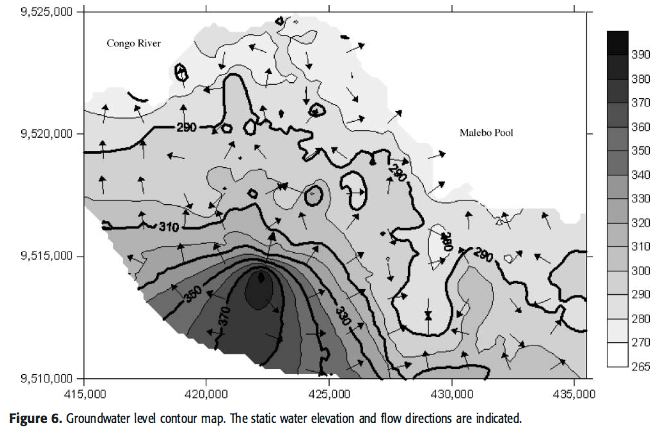

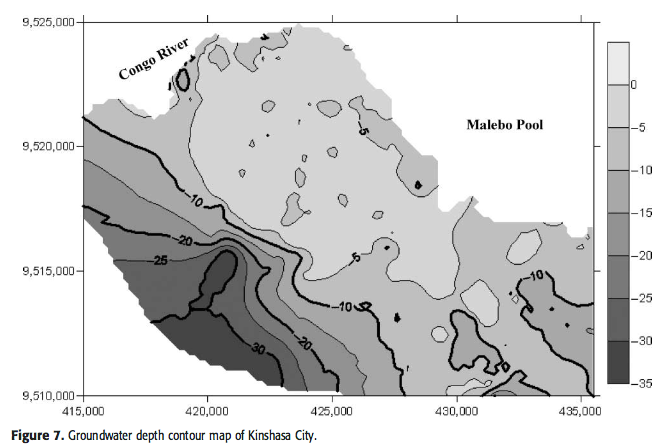

Data from hundreds of boreholes, indicated in Figure 5, have been used to construct water-table ground-water contour maps for Kinshasa City (Figures 6, 7). Fewer borehole data come from the hilly zone, hence the extrapolations to the south should be regarded with caution. Flow rate is related to porosity and permeability of the type lithology. Flow directions are related to drainage system, topography, rainfall intensity, and type of sediments.

These constructions suggest the irregularity of the static surface depth of the aquifer with a general deepening toward the southern hilly area. Recharge to the unconfined aquifers is from precipitation on the catchment area and its subwatersheds, in the interstream zones, by downward percolation through the porous loose fine sands and silts. The presence and amount of argillaceous and clayey component in the clastic deposits makes infiltration and recharge variable from place to place. Discharge of the water-table aquifer occurs as seepage through springs, swamps, and streams. The water-table aquifer overlays other unconfined aquifers. Examination of Figure 4 shows that, at the level of the top “Grès Polymorphes” and “Grès Tendre” units, buried gullies have entrenched, at places, deep enough to downcut the Inkisi siliciclastics. These buried channels have a coarse-grained clastic-gravelly fill. This fill is an important hydrogeologic unit. It represents a relatively deep aquifer with a characteristic high yield. Overlaying the gullied sequence is a layer of Kaoline sand (0 to 8 m [0 to 26 ft] thick). The Kaoline sands, spatially and in exposure, occupy low-lying parts of the undulating terrain of the Kinshasa plain. Temporally, the unit is affected, at the top, by limited dissection. Hydrogeologically, this unit has low hydraulic conductivity. It acts as an aquitard. The presence of these Kaoline sands and other more argillaceous beds enhance, at places, perched water-table or spatially localized aquifers. The stratigraphic relationship between the Kaoline sands and other units is not clear.

As mentioned elsewhere, the given hydrogeologic models are based on borehole data from the 1980s and earlier. More recent sets of subsurface information from Kinshasa City are not available to us. Groundwater conditions are susceptible to both climatic conditions and man-induced effects; therefore, the presented hydrogeologic model of the water-table aquifer has to be regarded as general indication for the conditions for the groundwater and its flow regime. In this regard, it is useful to recall that studies of meteorological records and climatic-geological proxies for the last 200 yr (Nicholson, 2001) showed that Africa has been affected by increased aridity particularly since the 1980s. It has also been stated that since the mid-1970s, rainfall declined in north Congo and in west Africa. Rainfall decline in north Congo is −3.2 ± 2.02% per decade (Nyong, 2005). However, we infer that man effects on groundwater level and flow direction are not high. The immaturity of urban structures in Kinshasa City, e.g., absence of subways, large pipelines, and deep foundations of civil structures, suggests that no serious human intervention on shallow groundwater flow regime occurs. This is further enhanced by both the insignificant harvesting of the water table and the abundance of rainfall. However, groundwater recharge and surface runoff should have been modified particularly in heavily populated zones of Kinshasa (e.g., the Ville and the downtown Cité). The presence of impervious surfaces, such as buildings, paved roads, as well as any existing storm drains, affects the recharge of the water table. Human effects, however, are higher with respect to groundwater quality. (...).

QUESTIONS

- Question 1 (Research): Describe the paradox

- Question 2 (Research): Describe the natural / geological purification process specifically for Kinshasa and the challenges of potable water

- Question 3 (Research): What are the specific steps of clensing the water here in Kinshasa by the water supplier?

- Question 4 (On-site): How many big, manual waterpumps do you see here? (They all look alike)

- Question 5 (On-site): Describe the process of water sourcing and refinement based on the information found on site. Why does this method need to be used related to the geological situation?

- Question 6 (On-site): Voluntarely add the coordinates and a picture relevant to the topic (water drilling, water spills, ...). Have at least your GPS on the picture to prove your presence.

CLAIMING YOUR FOUND

- Send the answers to riepichiep@gps-adventures.net

- According to the guidelines you may log immediately after sending in the answers. Should there be serious deviations or evidence that you were not on site the log might be deleted or we will work together to assure the education on the topic. Should you not have been onsite your log cannot be granted.

- A picture on the topic, but not of the site would be greatly appreciated, but isn't compulsory