The East London Museum is home to the world’s only surviving Dodo egg and a reconstruction of the flightless bird that lived on the island of Mauritius. The dodo egg draws thousands of visitors a year from all over the world.

The egg was given to the museum's curator Dr Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer in 1915 by her great aunt Lavinia.

In an article written by Dr Latimer in the South African Journal of Science,January 1953 vol. 49, No 6, at 208-210 she stated inter alia the following:

“In my possession is a large, light cream coloured egg. From the evidence that follows I maintain that this egg is that of a Dodo, and though I have searched the literature on Dodos I have found no reference to a Dodo’s egg anywhere in the world. The last evidence that the Dodo was alive was given by one, Benjamin Harry, who showed that the bird was alive in 1681 but was extinct by 1693.

This egg was given to me by my great aunt, whose maiden name was Lavinia Bean, shortly before she died in 1935 at the age of 98. As a young girl she was a keen collector of birds’ eggs and her father, Mr L. O. Bean also a naturalist, was deeply interested in botany.”

In the said article Dr Latimer stated that her great aunt received the egg from her father, Mr L. O. Bean on 15 January 1847 and that it has been in her family for 105 years. She concludes her article by saying that: “In the light of the evidence supplied and of the history of the egg I am satisfied that it is a Dodo egg.

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest genetic relative was the also extinct Rodrigues solitaire, the two forming the subfamily Raphinae of the family of pigeons and doves. The closest living relative of the dodo is the Nicobar pigeon.

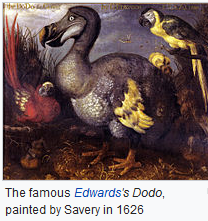

Subfossil remains show the dodo was about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall and may have weighed 10.6–21.1 kg (23–47 lb). The dodo's appearance in life is evidenced only by drawings, paintings, and written accounts from the 17th century. Because these vary considerably, and because only some illustrations are known to have been drawn from live specimens, its exact appearance in life remains unresolved, and little is known about its behaviour. Though the dodo has historically been considered fat and clumsy, it is now thought to have been well-adapted for its ecosystem. It has been depicted with brownish-grey plumage, yellow feet, a tuft of tail feathers, a grey, naked head, and a black, yellow, and green beak. It used gizzard stones to help digest its food, which is thought to have included fruits, and its main habitat is believed to have been the woods in the drier coastal areas of Mauritius. One account states its clutch consisted of a single egg. It is presumed that the dodo became flightless because of the ready availability of abundant food sources and a relative absence of predators on Mauritius.

The first recorded mention of the dodo was by Dutch sailors in 1598. In the following years, the bird was hunted by sailors and invasive species, while its habitat was being destroyed. The last widely accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662. Its extinction was not immediately noticed, and some considered it to be a mythical creature. In the 19th century, research was conducted on a small quantity of remains of four specimens that had been brought to Europe in the early 17th century. Among these is a dried head, the only soft tissue of the dodo that remains today. Since then, a large amount of subfossil material has been collected on Mauritius, mostly from the Mare aux Songes swamp. The extinction of the dodo within less than a century of its discovery called attention to the previously unrecognised problem of human involvement in the disappearance of entire species.

It’s commonly believed that the dodo went extinct because Dutch sailors ate the beast to extinction after finding that the bird was incredibly easy to catch due to the fact it had no fear of humans, (why it didn’t fear the creature many times its size is a mystery for another day). This is, for the for the most part, pretty accurate. It is noted that after sailors landed and settled on the island in 1958, the dodo’s population rapidly declined and other sources confirm that the dodo was indeed hunted by sailors looking for an easy snack, since the dodo’s ungainly gait and lack of a third axis of movement made it relatively easy to catch.

Yes, many were collected by the Dutch sailors and settlers, but there was something else that had a larger impact on their eventual extinction, invasive animals that the sailors brought with them on their ships; namely, rats, cats and pigs that went feral. There were never any rats on the island until they came with the ships and came ashore. Sailors always had a way of letting pigs or goats escape on various islands they visited. Cats were brought as working “pets.” So pigs and rats flourished in the wild, as they also had no natural enemies there. They actually sealed the fate of the dodo by eating all the dodo eggs they could find that were all on the ground in the simple unprotected dodo nests. The mother dodo would only lay one egg per season. It didn’t take long for the production of new baby dodo chicks to take a very steep decline. None of the nests were safe from foraging wild pigs and a multitude of newly introduced rats. The dodo as a species didn’t have a chance at that point, and they were doomed. Even those that had nested in remote places, soon had their young chicks or eggs consumed by the invaders.

If it weren’t for these marauding animals, the dodo may have been able to survive the onslaught of just the sailors and settlers hunting them on the 800 square miles of Mauritius. Many even became more cautious of human hunters, and adapted their behavior. It’s small consolation, but it is known that many of their hunters were bloodied by the dodo’s enormous hooked beak, in perhaps what was their last act of defiance. So yes, they did fight back. But there was no way to hide the nests and chicks from the pigs and the rats. The gentle trusting dodos paid the ultimate price. “The Last Dodo” may very well have been a single lonely chick or egg somewhere in the jungle that a scurrying rat came upon and decided to feast unaware that he or she, after a million years’ journey, was the last, the very last of them all.

This happened a mere 80 years after the first dodo to see a human come upon its peaceful shores, fearlessly and with simple, innocent curiosity waddled up to observe the new visitors and was slaughtered where he stood.

If dodos had never gone extinct, the word “dodo” would probably not have entered our lexicon as a derogatory word. “Dodo” probably would not have taken on the meaning of “dumb”. In a world with dodo birds, I suspect the word dodo would have meant peaceful, or curious. Perhaps it would have meant friendly, as in “Thanks, mate! That’s right dodo of you!”