Although not necessary, bringing a torch and a bottle of water will help you to see some of the features much clearer.

Start at the coords, a nice spot to grab a coffee before your walk, then follow the path around the pond until you reach the next stage.

Stage 2 - Your immersion into Rouken Glen’s geology begins at the large flattish slabs by the pond. Here you are immediately plunged into the Ice Age. The rock slabs here are made of sandstone and if you look closely at the surface you can see long straight scratches and gouges, these are known as ‘Striations’. The striations were made by deep glacier ice dragging rock fragments over the surface of the sandstone. They are much easier to see when the rock is wet so if you brought some water, pour it over the surface.

Question 1. Run your fingers over the striations and describe how they feel, are they rough or smooth?

Question 2. The glacier was part of a huge ice-sheet that came down from the Highlands. Look at the direction of the striations, do they run towards the pond or are they parallel to the pond?

Stage 3 - The large boulder on the grass beside the path is made up of a mixture of large and small rock fragments. This type of rock is called a conglomerate and nothing else matches it in the park. The boulder would have been carried here by the ice sheet and dropped when the ice melted. These are called ‘Erratics’.

Question 3. There is one particularly larger pebble low down at the front (path side), what type of rock do you think this pebble is?

Stage 4 - Near the noticeboard you will see a couple of unusual rocks that look like giant stone cannon balls. These are certainly not man-made. They were rescued from the Auldhouse Burn (a Scottish word for stream) in the gorge after the river bank collapsed in 2012 (see photo below) and may be an example of a ‘Concretion’. Concretions form within sediments before the surrounding layers harden into rock. They are made of mineral cement which hardens around some form of nucleus like a stone or organic matter. Concretions vary in size, shape, hardness, and colour, from objects that require a magnifying lens to be clearly visible to huge bodies 3m in diameter. Concretions are commonly misunderstood geologic structures. Descriptions dating from the 18th century attest to the fact that concretions have long been regarded as geological curiosities. They are not fossils, artifacts, or even debris from space, but a very common geologic phenomenon in all types of sedimentary rock; which include sandstone, shale, siltstone and limestone.

photo showing one of the Concretions when found in the Auldhouse Burn (before being moved to current location)

Question 4. Look at the smaller concretion. Why do you think it is the shape it is?

Stage 5 - Picnic rock provide exposures of ‘Giffnock Sandstone’. Although this was not quarried in the park, in the 19th century there were huge quarries working the same layer of sandstone in the area. These are now mostly filled in, so this is the best place to see this type of sandstone. It was one of the most important building stones in Glasgow and was also exported widely. Sandstone forms where sand is laid down and buried. Usually, this happens offshore from river deltas. When sand is deeply buried, the pressure of burial and slightly higher temperatures allow minerals to dissolve or deform and become mobile. The grains become more tightly knit together, and the sediments are squeezed into a smaller volume. Cementing material moves into the sediment, carried there by fluids charged with dissolved minerals. This sandstone was laid down in wide river channels. At the nearby waterfall, the layer, or bed, may be up to 15 m thick but the picnic rock bed seems much thinner – perhaps nearer the edge of the channel. The river channels were sometimes very large (km wide) in the Scottish Carboniferous. If you look closely you can see angled layers in the sandstone, this shows that the rock tilted after it was laid down.

Question 5. What angle are the layers?

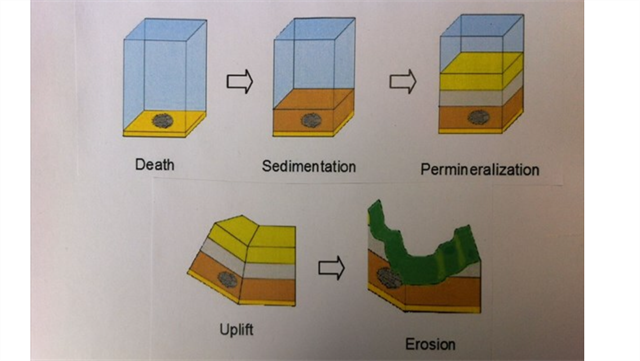

Stage 6 - Hidden away in the small wooded dell down the slope , west of Picnic rock is evidence of a much older woodland from around 325 million years ago. The swampy forests were very different then to today’s woodlands in the park. The trees were more like giant tree ferns and there would have been no birds, mammals or wild flowers. In the dell you can see a log of ‘Fossil Wood’ underneath the overhang. Logs often get stranded at channel margins or on sand bars. To become a fossil the log has to be protected from the elements. This means getting buried in sand, soil or mud. The best place for that is on the seabed or a river bed. There it is preserved due to a lack of oxygen which inhibits aerobic decomposition. As time passes, the log becomes buried deeper and deeper. What was mud or sand becomes compressed on its way to becoming rock. Safely sealed away underground, chemicals and minerals percolate through the sediment and the original wood gradually recrystallizes. In extreme cases, an entire tree can dissolve away, leaving a hollow where it once was. The minerals from the enclosing rock can gradually fill the hollow to create a natural cast of the original. In other cases, minerals from the rocks gradually impregnate the wood, changing its chemical composition and making it capable of surviving for as long as, or longer than, the rock enclosing it. Eventually the rock enclosing the fossil is eroded away, and the fossil is revealed (see diagram). The rocks below the fossil show cross bedding which suggest these were sand bars near the edge of the channel. Unless you are extremely tall or you brought a stepladder you will not be able to touch the fossil. Shine your torch up high under the overhand and you will see the rough bark that was turned to stone when the log became buried under sediment.

Question 6. Please provide a rough estimate of the size of the log.

A few metres to the left you can see another bit of rock that could potentially be another fossil.

Diagram of Fossil process

Please attach a photo to your log of you, your dog, gps, thumb or something personal to prove you were here. Please do not show any spoilers in your photo.

June 2019 the logging tasks for EC were updated. COs can now insist on a photo as proof of visit.

Further information about the geology of the park can be found in the Pavilion Visitor Centre.

Special thanks to Margaret Greene and the Geological Society of Glasgow for the help in creating this EarthCache.

PLEASE SEND YOUR ANSWERS TO THE QUESTIONS ABOVE BY EMAIL OR MESSAGE AT THE SAME TIME AS YOU LOG A FIND (IF YOU HAVE INTERNET TO LOG YOU HAVE INTERNET TO EMAIL). ANY LOGS ENTERED WITHOUT AN EMAIL BEING RECEIVED WILL BE DELETED WITHOUT NOTIFICATION.

| We have earned GSA's highest level: |

|