Portugues

A área do PNPG integra-se no Maciço Hespérico ou Maciço Ibérico que constitui uma das unidades estruturais da Península Ibérica e um segmento da Cordilheira Varisca da Europa. A edificação desta estrutura, pela actuação de forças compressivas, inicia-se no Devónico, há cerca de 380 Ma (milhões de anos), tendo-se prolongado até ao Pérmico (280 Ma) - orogenia Hercínica ou Varisca.

O Maciço Ibérico apresenta-se zonado, definindo-se habitualmente cinco zonas com características paleogeográficas, tectónicas, magmáticas e metamórficas distintas. A área do PNPG situa-se na Zona Centro-Ibérica (a zona mais interna da Cadeia Varisca). Esta zona é genericamente caracterizada pela existência de rochas muito deformadas e afectadas por elevado grau de metamorfismo e ainda pela predominância de rochas graníticas.

A acção dos agentes atmosféricos sobre as rochas graníticas, em conjugação com a rede de fracturas, origina uma paisagem típica das regiões graníticas, por vezes constituída por curiosas formas (penhas, bolas, caos de blocos, blocos pedunculados, pias)

A Meteorisaçao pode ser definida como a desintegração ou decomposição de rochas in situ e na gama de temperaturas ambiente encontradas na, e perto da superfície da Terra (Winkler, 1965). Alguns processos de intemperismo são físicos ou mecânicos e resultam na quebra ou fragmentação da rocha. Outros são químicos e envolvem a alteração de um ou mais dos constituintes minerais. Elementos biológicos também podem fazer contribuições importantes para ambos os tipos de intemperismo e, na verdade, vários processos, de vários tipos, geralmente trabalham em conjunto para produzir um manto de intemperismo ou regolito, que com a adição de materiais orgânicos se torna um solo.

A Meteorisaçao é um precursor essencial à erosão: sem desgaste preliminar da rocha, haveria pouca erosão.

Desintegração física

Investigadores anteriores atribuem grande importância a os processos físicos, e as variações temporais na insolação, envolvendo alternâncias de aquecimento e arrefecimento (Griggs, 1936), por exemplo, foram amplamente responsáveis por desintegração granular e por descamação e fragmentação (amplamente referido como esfoliação) em granito. O argumento é plausível. O Granito consiste em minerais de cores diferentes, com diferentes coeficientes de aquecimento e, por conseguinte, de expansão. As tensões geradas por alterações de aquecimento e arrefecimento foram considerados suficientes para causar fragmentação. Além disso, as rochas são maus condutores de calor, de modo que as rochas expostas ao sol seria aquecida e iria expandir, enquanto setores mais profundas não iria, e considerou-se que como resultado a pele exterior se separar do interior, resultando em descamação e fragmentação. Há muito que se compreendeu que granito expande sobre aquecimento.

Alteraçao química

Há alguma sugestão que as reações químicas ocorrem nos contornos de grão em condições secas, mas a infiltração de umidade e gases produz uma alteração acentuada e generalizada por processos tais como oxidação, redução, carbonatação, solução, hidratação e hidrólise. Devido à sua estrutura molecular, a água é um solvente ideal. Nenhum outro líquido pode dissolver uma variedade e volume de solutos. Foi alegado que a solução é essencial para intemperismo químico, não só por causa de seus efeitos diretos generalizadas, para todos os minerais são solúveis em certa medida, mas também porque se prepara estruturas cristalinas para mais reações. Hidratação implica dissociação da água ea liberação de íons de hidrogênio. Devido à sua elevada energia e pequeno raio iónico, eles são activos em substituição e eles prontamente entran e perturbam a estrutura cristalina

Formas de duas fases

Em um senso imediato, dois processos distintos, meteorisaçao e erosão, estão envolvidos na formação de pedras, rochas equilibradas e, juntos, eles são frequentemente referidos como o processo de duas fases ou mecanismo, embora os dois não estão necessariamente separadas e distintas na hora .

A primeira fase refere-se ao período de desgaste subsuperficial diferencial controlado por fractura, da segunda para a fase de erosão diferencial durante o qual grus é evacuada e as corestones são expostos como pedras.

Se a erosão supera a meteorisaçao, o regolito é erodido, enquanto "corestones" (o nucleo da rocha) permanecem como pedras. Se, no entanto, a meteorisaçao prossegue mais rapidamente do que a erosão, a maioria dos "corestones" localizados na zona próximo da superfície, são reduzidos a grus. Aqueles que persistem emergem à superfície, como pedras. Uma vez expostos eles já não estão em constante contato com a umidade, e tornar-se estáveis, enquanto a meteorisaçao continua no regolito, levando a uma situação comum de pedras sendo sustentada por espessuras consideráveis de grus

Em encostas íngremes ,o grus cai por gravidade. A maioria dos "corestones" são demasiado grande para ser transferidos e são deixados in situ, embora em algumas áreas alguns dos pedregulhos constituintes, falta de apoio, máquina de secar até formar uma massa caótica de pedras.

Mas seja qual for o resultado preciso, a exposição dos "corestones" por erosão diferencial é a segunda etapa no desenvolvimento de pedras.

TOR

Um tor normalmente aparece como uma pilha de lajes de rocha ou como uma série de placas na posição vertical, dependendo se o sistema de diaclasing dominante é horizontal ou vertical. O intemperismo age melhor ao longo dos planos planos, reduzindo assim a massa, originalmente sólida, primeiro para pilhas de placas e depois para uma pilha de blocos soltos. A maioria do tor do sudoeste da Inglaterra é encontrada nas massas de granito de Devon e Cornwall, embora sejam localmente chamadas de formas não-graníticas. É claro que nas massas de granito as tochas representam regiões de granito não caulinizado (processos hidrotermais) e são resíduos resultantes de desnudação diferencial de materiais duros e moles.

O termo também foi aplicado a vários tipos de massa rochosa residual de formas não graníticas; algumas delas são apenas remotamente relacionadas a torques típicos e deve-se ter cuidado para expandir o uso desse termo.

.

.

Para registrar este earthcache, envie-me um correio eletrónico com a resposta para as seguintes perguntas:

1) ¿Que foi mais rápida a eroçao o a meteorisaçao? Explique

2) ¿Cantos blocos forman o Tor? ¿Esta isolado, ou tem outros a beira?

3) Num dos blocos podese ver un furo, ¿É natural ou artificial?¿en cual dos blocos se atopa?

- Se acredita ter concluído com sucesso os objetivos desta Earthcache e já me enviou todos os requisitos conforme solicitado, por favor, sinta-se à vontade para a registar como encontrada. Posteriormente verificarei os requisitos enviados e, caso seja necessário, contacta-lo no sentido de efetuar as devidas correções ao seu registo.

-Todos os logs sem respostas, serão apagados sem aviso prévio.

-Imagens são opcionais, mas elas são bem-vindas e serão úteis para verificar a sua visita

English

The PNPG area is integrated in the Hesperian Massif or Iberian Massif which constitutes one of the structural units of the Iberian Peninsula and a segment of the Varisca Range of Europe. The construction of this structure, by the action of compressive forces, begins in the Devonian, about 380 Ma (millions of years), and has extended to the Permian (280 Ma) - Hercynic or Varisca orogeny.

The Iberian Massif is zoned, usually defining five zones with distinct paleogeographic, tectonic, magmatic and metamorphic characteristics. The PNPG area is located in the Central-Iberian Zone (the inner zone of the Varisca Chain). This zone is generally characterized by the existence of rocks that are very deformed and affected by a high degree of metamorphism and also by the predominance of granite rocks.

The action of the atmospheric agents on the granite rocks, in combination with the network of fractures, gives rise to a landscape typical of the granitic regions, sometimes constituted by curious forms (cliffs, balls, block chaos, pedunculated blocks, sinks)

Geomorphology

Weathering may be defined as the disintegration or decay of rocks in situ and in the range of ambient temperatures found at and near the Earth’s surface (Winkler, 1965). Some weathering processes are physical or mechanical and result in the break down or fragmentation of the rock. Others are chemical and involve the alteration of one or more of the constituent minerals. Biota also make important contributions to both types of weathering, and indeed, several processes, of various kinds, commonly work together to produce a weathered mantle or regolith, which with the addition of organic materials becomes a soil.

Weathering is an essential precursor to erosion: without preliminary weathering of the rock, there would be little erosion.

PHYSICAL DISINTEGRATION

Earlier investigators set great store by physical processes, and temporal variations in insolation, involving alternations of heating and cooling (Griggs, 1936), for example, were widely held responsible for granular disintegration and for flaking and spalling (widely referred to as exfoliation) in granite. The argument is plausible. Granite consists of minerals of different colours with different coefficients of heating and therefore of expansion. The stresses generated by alternations of heating and cooling were considered sufficient to cause fragmentation. In addition, rocks are poor conductors of heat, so that rocks exposed to the Sun would be heated and would expand, whereas deeper sectors would not, and it was considered that as a result the outer skin would separate from the inner, resulting in flaking and spalling. It has long been realised that granite expands on heating.

CHEMICAL ALTERATION

There is some suggestion that chemical reactions take place at grain boundaries in dry conditions, but infiltration by moisture and gases produces pronounced and widespread alteration by such processes as oxidation, reduction, carbonation, solution, hydration and hydrolysis. Because of its molecular structure, water is an ideal solvent. No other liquid can dissolve such a variety and volume of solutes. It has been claimed that solution is essential to chemical weathering, not only because of its widespread direct effects, for all minerals are soluble to some extent, but also because it prepares crystal structures for further reactions. Hydration implies dissociation of water and the release of hydrogen ions. Because of their high energy and small ionic radius they are active in substitution and they

readily enter and disrupt crystal lattices.

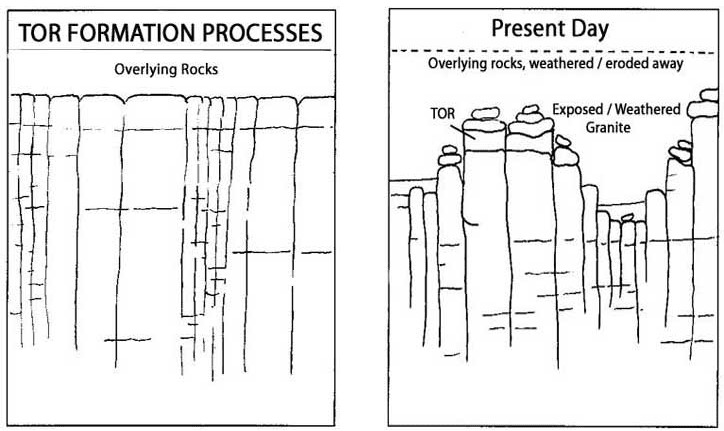

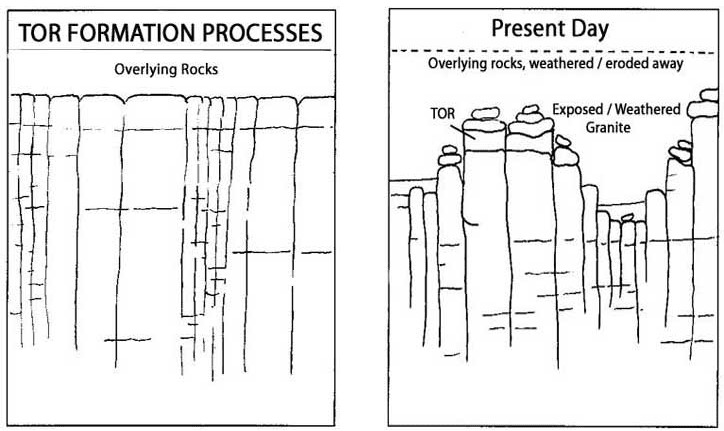

Two-stage forms

In an immediate sense, two distinct processes, weathering and erosion, are involved in the formation of boulders, balanced rock and together they are frequently referred to as the two-stage process or mechanism, though the two are not necessarily separate and distinct in time.

The first stage refers to the period of differential fracture-controlled subsurface weathering, the second to the phase of differential erosion during which grus is evacuated and the corestones are exposed as boulders.

If erosion outpaces weathering, the regolith is eroded, while corestones remaining as boulders. If, however, weathering proceeds more rapidly than erosion, most corestones located in the near surface zone are reduced to grus. Those that persist emerge at the surface as boulders. Once exposed they are no longer in constant contact with moisture, and become stable, while weathering continues in the regolith, leading to the common situation of boulders being underlain by considerable thicknesses of grus

On steep slopes the grus falls away under gravity. Most of the corestones are too massive to be moved and are left in situ, though in some areas some of the constituent boulders, lacking support, tumble down to form a chaotic mass of boulders.

But whatever the precise result, the exposure of the corestones by differential erosion is the second stage in the development of boulders.

TOR

A tor normally appears as a pile of rock slabs or as a series of plates in vertical position, depending on whether the dominant diaclasing system is horizontal or vertical. The weathering acts best along the flat planes, thus reducing the mass, originally solid, first to stacks of slabs and then to a pile of loose blocks. Most of the tor of southwestern England are found in the granite masses of Devon and Cornwall, although they are locally termed non-granite forms. It is clear that in the granite masses the torches represent regions of un-kaolinised granite (hydrothermal processes) and are residues resulting from differential denudation of hard and soft materials.

The term tor has also been applied to various types of residual rock mass of non-granite forms; some of these are only remotely related to typical torques and care must be taken to expand the use of this term.

.

.To log this earthcache, send me an email/message with the answer to the following questions:

1) What was the fastest process, weathering or erosion? Explain

2) How many blocks form or Tor? Is it isolated, or there are others in the area?

3) In one of two blocks you can see a hole, Is it natural or artificial? In which of the blocks it´s placed?

-If you believe you have successfully completed this Earth Cache goals and has already sent to me all the requirements as requested, Please, feel free to log it as found. Later i will verify the requirements sent and, if necessary, contact you in order to make the necessary corrections to your log.

-Logs without answers, will be deleted without notice.

-Pictures are optional, but they are welcome and will be usefull to verify you visit