As you walk along Davis Ponds trail in this area, you will see several rows of vertical poles about 5 feet tall going across the landscape, probably from peeled lodgepole pines harvested locally. The Park has removed the barbed wire fencing that was originally held up by these poles, but has left these century-old poles in place as a reminder of their purpose in the history of this place.

When the Staunton family and other settlers arrived in this area and wanted to acquire and develop property here, they were the beneficiaries of one of the great movements of the American Dream in U.S. history. Homesteading was the means by which most of the private land in the wide expanses of the Midwest and western United States came under private ownership. The historical meaning of the word Homesteading in the United States usually relates to acquisition of land through the Homestead Act of 1862 and similar acts before and after that facilitated land acquisition by citizens. In this sense, the definition of a Homestead is land acquired from U.S. public lands through a formal process of filing an application, living on the land, and making a living from it through farming or ranching.

The distribution of Government lands had been an issue since the Revolutionary War. At the time of the Articles of Confederation, the major controversy related to land measurement and pricing. Early methods for allocating unsettled land outside the original 13 colonies were arbitrary and chaotic. Boundaries were established by stepping off plots from geographical landmarks. As a result, overlapping claims and border disputes were common. The Land Ordinance of 1785 finally implemented a standardized system of Federal land surveys that eased boundary conflicts. Using astronomical starting points, territory was divided into a 6-mile square called a township prior to settlement. The township was divided into 36 sections, each measuring 1 square mile or 640 acres each. Sale of public land was viewed as a means to generate revenue for the Government rather than as a way to encourage settlement. Initially, an individual was required to purchase a full section of land at the cost of $1 per acre for 640 acres. The investment needed to purchase these large plots and the massive amount of physical labor required to clear the land for agriculture were often insurmountable obstacles.

In the mid-1800s, popular pressure to change policy arose from the evolving economy, new demographics, and shifting social climate of early 19th-century America. Rising prices for corn, wheat, and cotton enabled large, well-financed farms, particularly the plantations of the South, to force out smaller ventures. Displaced farmers then looked westward to un-forested country that offered more affordable development. Prior to the war with Mexico (1846–48), people settling in the West demanded “preemption,” an individual's right to settle land first and pay later (essentially an early form of credit). Eastern economic interests opposed this policy as it was feared that the cheap labor base for the factories would be drained. After the war with Mexico, a number of developments supported the growth of the homestead movement. Economic prosperity drew unprecedented numbers of immigrants to America, many of whom also looked westward for a new life. New canals and roadways reduced western dependence on the harbor in New Orleans, and England's repeal of its corn laws opened new markets to American agriculture.

Despite these developments, legislative efforts to improve homesteading laws faced opposition on multiple fronts. As mentioned above, Northern factories owners feared a mass departure of their cheap labor force and Southern states worried that rapid settlement of western territories would give rise to new states populated by small farmers opposed to slavery. Preemption became national policy in spite of these sectional concerns, but supporting legislation was stymied.

With the secession of Southern states from the Union and therefore removal of the slavery issue, finally, in 1862, the Homestead Act was passed and signed into law. The new law established a three-fold homestead acquisition process: filing an application, improving the land, and filing for deed of title. Any U.S. citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. Government could file an application and lay claim to 160 acres of surveyed Government land.

Physical conditions on the frontier presented even greater challenges. Wind, blizzards, and plagues of insects threatened crops. Open plains meant few trees for building, forcing many to build homes out of sod. Limited fuel and water supplies could turn simple cooking and heating chores into difficult trials. Ironically, even the smaller size of sections took its own toll. While 160 acres may have been sufficient for an eastern farmer, it was simply not enough to sustain agriculture on the dry plains, and scarce natural vegetation made raising livestock on the prairie difficult. As a result, in many areas, the original homesteader did not stay on the land long enough to fulfill the claim.

Homesteaders who persevered were rewarded with opportunities as rapid changes in transportation eased some of the hardships. Six months after the Homestead Act was passed, the Railroad Act was signed, and by May 1869, a transcontinental railroad stretched across the frontier. The new railroads provided easy transportation for homesteaders, and new immigrants were lured westward by railroad companies eager to sell off excess land at inflated prices. The new rail lines provided ready access to manufactured goods and catalog houses like Montgomery Ward offered farm tools, barbed wire, linens, weapons, and even houses delivered via the rails.

The act enabled anyone of at least twenty-one or the head of a family, including single women and freed slaves, to acquire up to 160 acres of land from the public domain. An entrant had to file a claim, reside on the land for five years, build a home, make improvements, and farm the land. He or she also had to be a citizen or acquire citizenship prior to satisfying the entry requirements. After six months, an entrant had the option of foregoing the five-year residency requirement and simply paying $1.25 per acre to acquire title. In return, the entrant would receive a patent transferring the property from the public domain to the private individual. Land acquisition under the act ended in the continental United States in 1976 and in Alaska in 1986.

Amendments and extensions to the original Homestead Act were put into law up until 1916, aimed at expanding the program to dry-land farming with irrigation, development of forested lands, development on non-irrigable dry lands for farming, and development of land not suitable for farming but could support animal grazing.

Homesteading had a tremendous impact on the settlement of Colorado. Between 1868 and 1961, it was reported that 107,618 successful land entries resulted in 22,246,400 acres of land entering private hands there. This does not include mineral lands acquired as Mineral Entry Patents. Despite fraudulent activities associated with some of the acquisitions, the ability of individuals and families to become owners of land through hard work has become a symbol of the promise of the American Dream, where anyone with drive and determination can improve their condition by taking advantage of available opportunities. Agricultural production and taxes on those lands stimulated economic development throughout the state. Today, we still see the impact of the Homesteading era in the rural historic landscapes that have endured.

Imagine yourself alongside Archibald and Rachael Staunton as they started the homesteading path in 1916 here in what was to become Staunton State Park. They were both medical doctors. Archie suffered from tuberculosis in West Virginia before moving west to Denver about 1900. There he established a medical practice, treating patients and reviewing insurance claims for medical treatment. He usually spent his work week in Denver and came to the “ranch” nicknamed Sherwood Forest on weekends. Rachael spent the summers (at least 6 months a year) at the ranch, and spent the winters in Denver, where they owned a house on Capital Hill. Rachael treated many patients at the ranch, delivering babies, for both Ute tribe members and other local settlers.

To be granted title to the property, they had to build a cabin of at least 12 x 14 feet, raise crops and livestock, and make other improvements to the land. The Staunton cabin was completed in 1918, and a kitchen was added a few years later. They terraced the land near their cabin for growing crops, and the stone walls of the terraces are still visible today. A ditch was also dug from Black Mountain Creek near the current intersection of SR and OM trails to the area of the terraces for irrigation purposes. Several other cabins were built on their property in the following decade, and they were rented out for the summer. They also had summer camps with tents for treating tuberculosis patients and for family vacations. They acquired additional land in this area as a result of deeds from patients they had treated.

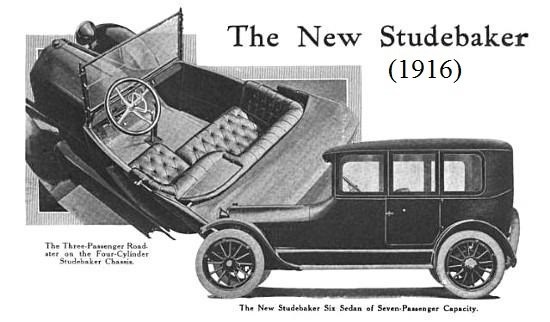

Think of the technology that they had available at that time. This cache has an example of the automobile technology, a model of a 1916 Studebaker truck, and we know that the Stauntons owned a 1928 Pierce Arrow car, and they later bought a used 1919 Pierce Arrow vehicle to use its engine for powering the sawmill, the ruins of which are still at the OM/MC trail intersection. Lumber was another way that they could finance some of the property improvements. Sales of automobiles in the U.S. rose from 8,000 in 1900 to over 9 million in 1920, producing a large increase in demand for gasoline. Oil production in Colorado began about 1880 near Florence and Canon City, and the near Boulder in 1900, and local refineries became available. Previously, wood and coal were used to power local industry and the railroads that developed in the late 19th century.

This cache is located within Staunton State Park, which has one public entrance along S. Elk Creek Road, six miles west of Conifer, about 1.5 miles off U.S. Highway 285. Parking along either side of S. Elk Creek Road and Upper Ranch Road adjacent to the park boundary is prohibited. All vehicles entering the park must have a daily park pass ($10) or a CO state park annual or special pass.

This cache is located within Staunton State Park, which has one public entrance along S. Elk Creek Road, six miles west of Conifer, about 1.5 miles off U.S. Highway 285. Parking along either side of S. Elk Creek Road and Upper Ranch Road adjacent to the park boundary is prohibited. All vehicles entering the park must have a daily park pass ($10) or a CO state park annual or special pass.

The Park is open year-round, and day use hours at 6:00 am to 10:00 pm. A walk-in campground (up to ¼ mile from parking) is open for public use, and overnight parking is currently permitted only for those staying in the campground. During summer and autumn weekends, the park may reach capacity, and cars are allowed to enter only if a parking space is available. Horse trailers are admitted if space is available for parking trailers, in the new, dedicated, unpaved parking lot. All Park trails are natural surface, some trails are hiker-only, but other trails are multiuse for bicycles and horses also. Information about the park can be found at Staunton State Park website

All visitors must follow park rules and regulations. These include dogs on leash at all times, clean up after pets, travel on developed trails to the extent feasible, leave no trace, respect areas closed for resource management, and be careful around wildlife (especially mountain lions, coyotes, and black bears). Fires are strictly prohibited, except for camp stoves with an on/off switch in the designated campsites and grilles found in the picnic areas. No motorized vehicles are allowed on trails within the Park. An exception is the special tracked chairs that the Park offers to visitors who cannot access selected trails on their own mobility. Pack your own trash out of the back country, and trash receptacles are located near the parking areas. Also, be prepared for changing weather, bring adequate water and footwear, and trails may be snow-covered or icy in winter.