Road to Revolution ~ Five men signed the Declaration of Independence for

New Jersey.

”Signers"

This cache is located at the Abraham Clark Gravesite.

”Signers"

This cache is located at the Abraham Clark Gravesite.

In the fall of 1776, a wealthy Princetonian named Richard Stockton traveled to upstate New York to inspect troops in General George Washington’s army. These were the dark days of the American Revolution, when the Continental Army seemed to be doing more retreating than fighting. Stockton, an urbane attorney, was appalled to find many troops, among them his fellow New Jerseyans, “barefooted and barelegged.” In a heartfelt letter to his friend Abraham Clark, who lived in what is now Roselle, Stockton wrote, “There is not a single shoe or stocking to be had in this part of the world, or I would ride a hundred miles through the woods to purchase them with my own money.”

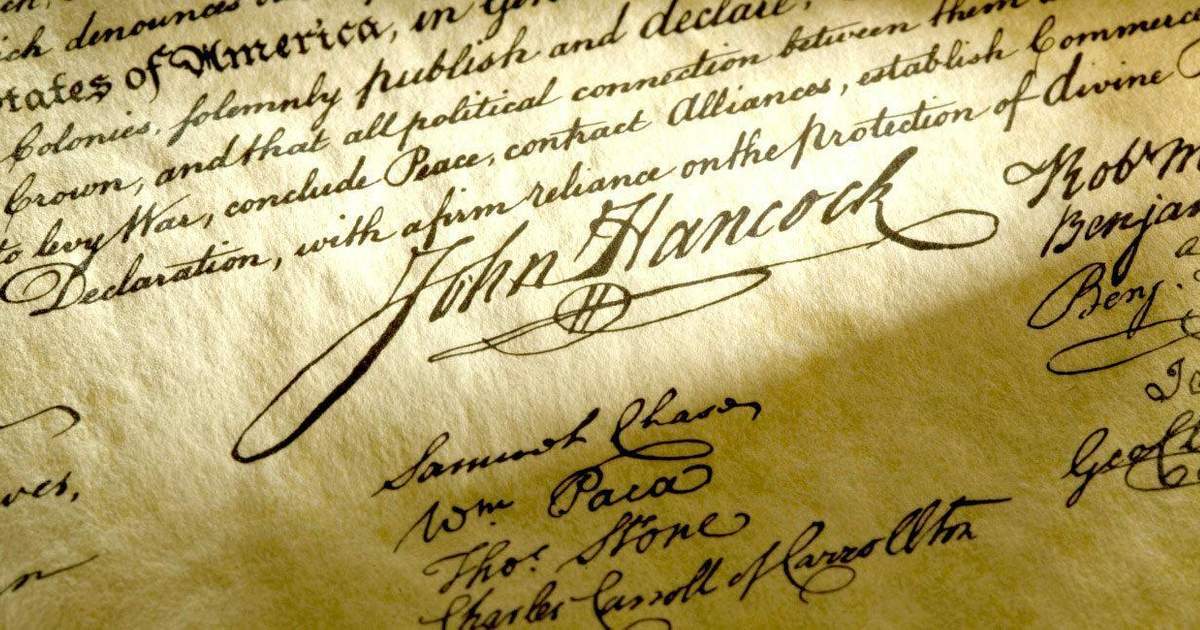

Earlier that same year, 56 men put their lives on the line by signing the Declaration of Independence. Stockton was one of five who signed on behalf of New Jersey. Their stories are often overshadowed by those of other, more famous founding fathers—named Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, and Washington. But the stories of the New Jersey signers are fascinating just the same and offer a chance to slip back in time, learn more about New Jersey, and visit sites associated with the signers.

The 5 signers of the Declaration of Independence from New Jersey are; Abraham Clark, John Hart, Francis Hopkinson, Richard Stockton, and John Witherspoon. There were a total of 56 Patriots from the 13 Colonies who signed the Declaration of Independence below is what happened to these brave Patriots.

Abraham Clark (1726-1794)—Abraham Clark was a farmer, surveyor and politician who spent most of his life in public service. He was a member of the New Jersey state legislature, represented his state at the Annapolis Convention in 1786, and was opposed to the Constitution until it incorporated a bill of rights. He served in the United States Congress for two terms from 1791 until his death in 1794.

John Hart (1711-1779)—John Hart became the Speaker of the Lower House of the New Jersey state legislature. His property was destroyed by the British during the course of the Revolutionary War, and his wife died three months after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. During the ravaging of his home, Hart spent time in the Sourland Mountains in exile.</p>

Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791)—Francis Hopkinson was a judge and lawyer by profession but also was a musician, poet and artist. When the Revolutionary War was over, he became one of the most respected writers in the country. He was later appointed Judge to the U.S. Court for the District of Pennsylvania in 1790.</p>

Richard Stockton (1730-1781)—Richard Stockton was trained to be a lawyer and graduated from the College of New Jersey. He was elected to the Continental Congress in 1776 and was the first of the New Jersey delegation to sign the Declaration of Independence. In November 1776 he was captured by the British and was eventually released in 1777 in very poor physical condition. His home at Morven was destroyed by the British during the war and he died in 1781 at the age of 50.</p>

John Witherspoon (1723-1794)—John Witherspoon was the only active clergyman among the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He was elected to the Continental Congress from 1776-1782, elected to the state legislature in New Jersey from 1783-1789 and was the president of the College of New Jersey from 1768-1792. In his later years he spent a great deal of time trying to rebuild the College of New Jersey (Princeton).</p>

History of New Jersey’s Five Who Signed.

Abraham Clark THE PRICE OF FREEDOM

Born in Elizabethtown in 1726, Abraham Clark worked as a surveyor and the local go-to guy for legal advice. He was known as the Poor Man’s Counselor due to his willingness to help folks with their land disputes, mortgages, and other small legal matters, often for no payment. But this hero of the middle class paid a horrible price during the Revolutionary War. Clark had two sons, Aaron and Thomas, captured during battle. It’s believed Thomas was tossed aboard the prison ship Jersey. Such ships made on-land prisons look like palaces. A veritable cesspool of dysentery, small pox, and any other contagion imaginable, the Jersey was like a floating morgue, with scores of prisoners dying and being dumped overboard daily to clear the putrid decks.

Clark’s other son was thrown into a New York dungeon called the Sugar House, where his fellow prisoners—themselves in dire straits—felt so bad for his condition and lack of nourishment that they passed him food through a keyhole. Both sons were eventually freed, probably as part of a prisoner exchange.

After the war, Clark served New Jersey as a representative to the Continental Congress. In 1794, he suffered sunstroke while watching some men build a bridge on his property and died hours later. A replica of his birthplace, owned by the local chapter of the New Jersey State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, stands today on part of Clark’s old property at 101 West Ninth Avenue in Roselle and is open one day each fall as part of Union County’s Four Centuries in a Weekend home tour. The Union County town of Clark is named for the signer, who is buried with his sons in nearby Rahway Cemetery (1670 Saint Georges Avenue, Rahway). Look for a 10-foot-tall obelisk engraved with the signer’s name.

Francis Hopkinson design for a U.S. flag

Philadelphia-born Francis Hopkinson married one of patriot Joseph Borden’s daughters, who hailed from—where else?—Bordentown. Hopkinson was trained in law but excelled in multiple fields, including chemistry, music, engineering, writing, and art. He wrote operas, songs, and satires. During the early meetings of the Continental Congress, Hopkinson often drew caricatures of his fellow congressmen. His biggest claim to fame? He is credited in congressional records as having conceived a design for a U.S. flag, though, like many a long-suffering artist, Hopkinson never got the recognition he craved. For his flag design, he asked Congress for “a quarter cask of the public wine.” Congress told him to take a hike. Furious, Hopkinson quit his government job. His original design is believed to have included stars and stripes. The stars had six points, resembling those on Hopkinson’s family crest.

Like many of the Founding Fathers, Francis Hopkinson was a man of many talents. An artist, a musician, a poet, a lawyer, a businessman, and a politician, he seemed to do just about everything. Included in his skillset was a knack for artistic design. This led to his involvement in a number of design projects for the United States.

Hopkinson developed many seals and symbols during the US’s infancy, including the Grand Seal of the United States. However, there’s no doubt that his most important project was the national flag. He designed it while serving on the Continental Marine Committee, in a position known today as the Secretary of the Navy. In 1777, the flag was adopted as the US’s official national flag, and Hopkinson became the creator of the Stars and Stripes.

Hopkinson’s home in Bordentown—where he settled with his wife—was ransacked during the Revolutionary War, though he was unharmed. In a letter to his friend, mentor, and fellow inventor, Ben Franklin, he wrote of the event, “I have suffered much by the invasion of the Goths and Vandals. I was obliged to fly from my home at Bordentown with my family and leave all my effects in statu quo. The savages plundered me to their heart’s content—but I do not repine, as I really esteem it an honour to have suffered in my Country’s Cause and in Support of the Rights of Human Nature and of Civilized Society. I have not the abilities to assist our righteous cause by personal Prowess and Force of Arms, but I have done it all the service I could with my pen.”

You can visit the house at 101 Farnsworth Avenue, Bordentown. Occupied by various businesses today, it’s partially open to the public, and includes wall displays in tribute to the signer. Hopkinson, who died in 1791 at age 53, is buried at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia (admission: $2 admission), though the precise location of his grave is unknown. A modern stone, usually marked with a colonial flag, indicates the approximate spot.

John Witherspoon PRINCETON’S REVEREND

Scottish-born John Witherspoon was a minister recruited by wealthy Jerseyans to become president of the college that later became Princeton University. Reverend Witherspoon first declined the post because his wife was afraid of sea voyages and believed that Scotland was far more civilized than New Jersey in the 1760s. But Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, who would eventually join Witherspoon in signing the Declaration, persuaded her to change her mind.

Witherspoon ended up heading the college and became the only active church minister out of 56 men to sign the Declaration of Independence. He was 53. Witherspoon, who coined the word “Americanism”—meaning a phrase or manner of speaking that is distinctly American—lost his son to the Revolutionary War and saw the precious library that he donated to the school ransacked and burned.

The Reverend has received good press in recent years because of the achievements of a descendant—Reese Witherspoon. If you visit Princeton today, you can stroll along Witherspoon Street near the university campus, lift a glass in his memory at the Witherspoon Grill (57 Witherspoon Street), and inspect his grave in the President’s Lot on the southwest edge of Princeton Cemetery (29 Greenview Avenue; 609-924-1369).

Witherspoon lived in two Princeton homes. One, dubbed Tusculum, is a private residence and not open to the public. The other, known as the President’s House or Maclean House, stands on the campus facing Nassau Street and is home to the university’s alumni offices.

Honest John Hart

“Honest” John Hart was a New Jersey farmer who owned about 400 acres of land and a couple of grist and saw mills. Though not highly educated, Hart interested himself in the affairs of the world outside his Hunterdon County farm. He even served as a judge.

The year 1776 was difficult for Hart. In October, his wife fell sick and died. By December, the British were in Hart’s neck of the woods. When troops drew near his home, the still-grieving widower sent his young children to stay with friends, then hid out in the nearby hills. Legend says Hart slept in caves, doghouses, and snowy fields while the British hunted him—as one historian says—“like a noxious beast.” Historians think he sought shelter in a rock formation in the region. Although he probably spent no more than a month on the run, it was undoubtedly stressful for a man in his 60s.

Hart’s house and farm were probably plundered or damaged, but he wasn’t ruined. A year and a half after his runaway adventure, Hart generously hosted George Washington at his place and allowed 12,000 of the general’s troops to camp in his fields. His grave is marked with an obelisk in First Baptist Church Cemetery on West Broad Street in Hopewell. The tombstone incorrectly reports the date of Hart’s death as 1780. He died in 1779.

Richard Stockton endured suffering

And what of poor Richard Stockton? It’s arguable that he endured greater physical suffering than any of the other 56 signers of the Declaration. Because of his support of the patriotic cause, he was yanked from bed in Monmouth County, where he was hiding from the British, and flung into prison in Perth Amboy (and later moved to New York City). There he languished for months without food and adequate shelter until his release on parole. (The terms of his release are unclear; it’s possible he recanted his patriotic ideals to gain his release. No other signer was forced to make such a concession.)

Devastated physically, he returned to his pillaged home, Morven, where he recovered his health but died from cancer in 1781 at age 50. Morven endured and was the official residence of the New Jersey governor until 1982. It serves as a museum today (historicmorven.org). Stockton was buried in Stony Brook Quaker Meeting House Cemetery (470 Quaker Road, Princeton), where you’ll find a marker instead of a modern gravestone in his memory.

How does the state commemorate Stockton’s sacrifice today? With a charming hamlet named Stockton in Hunterdon County, Stockton College in Pomona, and, of course, a rest area in his honor on the New Jersey Turnpike in Mercer County.

Fate of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

The following is often published and cited concerning the fate of the Signers, but its accuracy is doubtful, and should only be taken as "traditional" rather than historical. See the end for links to other sources on the subject.

Five signers were captured by the British as traitors, and tortured before they died.

Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Two lost their sons serving in the Revolutionary Army; another had two sons captured.

Nine of the 56 fought and died from wounds or hardships of the Revolutionary War.

They signed and they pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor. What kind of men were they?

Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists. Eleven were merchants, nine were farmers and large plantation owners; men of means, well educated. But they signed the Declaration of Independence knowing full well that the penalty would be death if they were captured.

Carter Braxton of Virginia, a wealthy planter and trader, saw his ships swept from the seas by the British Navy. He sold his home and properties to pay his debts, and died in rags.

Thomas McKeam was so hounded by the British that he was forced to move his family almost constantly. He served in the Congress without pay, and his family was kept in hiding. His possessions were taken from him, and poverty was his reward.

Vandals or soldiers looted the properties of Dillery, Hall, Clymer, Walton, Gwinnett, Heyward, Ruttledge, and Middleton.

At the battle of Yorktown, Thomas Nelson, Jr., noted that the British General Cornwallis had taken over the Nelson home for his headquarters. He quietly urged General George Washington to open fire. The home was destroyed, and Nelson died bankrupt.

Francis Lewis had his home and properties destroyed. The enemy jailed his wife, and she died within a few months.

John Hart was driven from his wife's bedside as she was dying. Their 13 children fled for their lives. His fields and his gristmill were laid to waste. For more than a year he lived in forests and caves, returning home to find his wife dead and his children vanished. A few weeks later he died from exhaustion and a broken heart.

Norris and Livingston suffered similar fates. Such were the stories and sacrifices of the American Revolution. These were not wild-eyed, rabble-rousing ruffians. They were soft-spoken men of means and education. They had security, but they valued liberty more. Standing tall, straight, and unwavering, they pledged: "For the support of this declaration, with firm reliance on the protection of the divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other, our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor."

They gave you and me a free and independent America. The history books never told you a lot about what happened in the Revolutionary War. We didn't fight just the British.

We were British subjects at that time and we fought our own government!

Some of us take these liberties so much for granted, but we shouldn't. So, take a few minutes while enjoying your 4th of July holiday and silently thank these patriots. It's not much to ask for the price they paid. Remember: freedom is never free!

Abraham Clark Gravesite

Abraham Clark was one of five signers of the Declaration of Independence representing New Jersey Rahway Cemetery is the resting place of Declaration of Independence signer Abraham Clark (February 15, 1726 – September 15, 1794).

A large gravestone in the cemetery marks the burial site of Abraham Clark and his wife Sarah. Abraham Clark served in the Continental Congress 1776-1778, 1780-1783 and 1786-1788. He later served in the United States House of Representatives in the Second and Third Congresses (during the presidency of George Washington) from March 4, 1791, until his death. [1] Clark was born in nearby Roselle, and Clark Township is named for him.

Abraham Clark was born into the life of a farmer at what is now Elizabeth, New Jersey. His father saw an aptitude for mathematics and felt that he was too frail for the farm life and so young Abraham was tutored in mathematics and surveying. He continued his own study of the Law while working as a surveyor.

”plaque"

”plaque"

He later practiced as an attorney and in this role is said to have been quite popular because of his habit of serving poor farmers in the community in cases dealing with title disputes. In succeeding years he served as the clerk of the Provincial Assembly, High Sheriff of Essex (now divided into Essex and Union) County.

Elected to the Provincial Congress in 1775, he then represented New Jersey at the Second Continental Congress in 1776, where he signed the Declaration of Independence. He served in the congress through the Revolutionary War as a member of the committee of Public Safety.

He retired and was unable to attend the Federal Constitutional Convention in 1787, however he is said to have been active in community politics until his death in 1794. Clark Township, New Jersey, is named in his honor.