|

Le marmitte dei giganti del Fiume Metauro |

|

La forra di San Lazzaro

Lungo il tratto vallivo compreso fra Calmazzo e Fossombrone, il Fiume Metauro taglia trasversalmente la dorsale dei Monti della Cesana, costituita da rocce calcareo-selcifere e calcareo marnose di età giurassico superiore-eocenica (formazioni della Maiolica, Marne a Fucoidi, Scaglia Bianca e Scaglia Rossa). Il fondovalle del tratto vallivo considerato è occupato da una piana alluvionale relitta, relativamente ampia e pensile sull'alveo attivo (terrazzo con deposito del Pleistocene superiore). Il corso attuale del Metauro si trova quindi più o meno infossato entro questa piana, dalla quale è separato da ripide scarpate di altezza variabile da 5-6 m a oltre 25 m.

All'altezza di S. Lazzaro di Fossombrone, nel tratto in cui il corso fluviale incontra i calcari selciferi biancastri della formazione della Maiolica, particolarmente resistenti all'erosione, le scarpate si avvicinano notevolmente e la loro altezza raggiunge quasi i 30 m. Il Metauro inizia qui a percorrere per circa 500 m una stretta e suggestiva forra dalle pareti strapiombanti, la cui ampiezza al livello del fiume non supera i 13,5 m; le acque sono piuttosto profonde, con punte massime superiori ai 17 m. La forra è attraversata dal Ponte dei Saltelli o di Diocleziano, che permette una suggestiva visione dall'alto sia della stessa che delle caratteristiche marmitte dei giganti in sponda sinistra.

Fig.1: Sezione geologica della Forra di S. Lazzaro

Fig.1: Sezione geologica della Forra di S. Lazzaro

La formazione della Forra di S. Lazzaro, così come la vediamo oggi, risale certamente all’Olocene in quanto si tratta una forma tuttora attiva che incide il terrazzo del Pleistocene superiore. La superficie di tale terrazzo, che corrisponde più o meno alla sede stradale lungo il tratto Fossombrone-Calmazzo, indica infatti la posizione più elevata raggiunta dal letto del Metauro durante l’ultimo glaciale (Pleistocene sup.), tra 20.000 e 30.000 anni fa circa. Le ghiaie alluvionali del terrazzo ricoprono e livellano un substrato roccioso con superficie estremamente irregolare, solcata da numerose depressioni sepolte. Una di queste depressioni, di forma e dimensioni paragonabili a quelle dell’attuale forra, rappresenta un antico percorso del Metauro sepolto dai sedimenti alluvionali. Durante la sua storia evolutiva, nel tratto vallivo considerato, il Metauro ha pertanto più volte inciso e colmato forre nei calcari della Maiolica.

In Fig.2 vediamo un’ipotesi sulla nascita ed evoluzione delle forre di S. Lazzaro:

- Riss-Wurm ― inizio Wurm: instaurazione del primitivo corso d'acqua che inizia ad incidere la roccia sino al Calcare Rupestre;

- Wurm inf. ― medio: il substrato roccioso è ricoperto dall'espansione della conoide del Fosso di S. Lazzaro;

- Wurm sup. ― Olocene: la ripresa dell'attività tettonica, a discapito della sedimentazione, determina la creazione di un altro canale parallelo a quello sepolto.

Fig.2: Ipotesi sulla nascita ed evoluzione delle forre di S. Lazzaro

Fig.2: Ipotesi sulla nascita ed evoluzione delle forre di S. Lazzaro

Le marmitte dei giganti

Le pareti della forra incisa nei pressi di S. Lazzaro di Fossombrone dal Fiume Metauro nei calcari selciferi della formazione della Maiolica presentano splendidi esempi di particolari forme d'erosione fluviale, le cosiddette "marmitte dei giganti". Queste forme, dette anche caldaie, caldaie di evorsione o semplicemente marmitte, sono state prodotte dall'erosione vorticosa (evorsione) della corrente. Si tratta di cavità tipicamente subcilindriche di diametro e profondità variabili da pochi centimetri a diversi metri. Le marmitte sono la forma dominante dell'erosione fluviale in alvei molto stretti e in presenza di flussi idrici anche occasionali, ma molto veloci e turbolenti. Il moto vorticoso dell'acqua a contatto col fondo o con le pareti dei canali fluviali fa roteare piccoli ciottoli che esercitano azione abrasiva (Fig.3―1); l'insistere di vortici in uno stesso punto può creare piccole concavità, che vanno a formare gli embrioni delle marmitte, all'interno dei quali possono venire intrappolati dei ciottoli (Fig.3―2). Questi, roteando spinti dal moto vorticoso della corrente, strisciano e urtano contro le pareti delle concavità e, accentuando così l'azione di trapanazione, vanno a incrementare via via le dimensioni della marmitta stessa (Fig.3―3).

Fig.3: Schema formazione marmitta

Fig.3: Schema formazione marmitta

Il processo prosegue fino a quando la forma si estingue, con l'apertura di varchi nelle pareti o per un eccessivo approfondimento che intrappolando troppi ciottoli e/o ciottoli troppo pesanti, rendendo inefficace l'azione evorsiva. Non sempre l'erosione è in grado di produrre marmitte, ma spesso produce concavità e solchi di varia forma e dimensioni, che si associano generalmente alle marmitte vere e proprie.

Nel caso della forra di S. Lazzaro, le marmitte sono particolarmente ben sviluppate sotto il ponte dei Saltelli o di Diocleziano, dove si sono potute produrre e preservare grazie alla notevole durezza dei calcari della Maiolica e all'alta velocità e turbolenza della corrente durante le fasi di piena. Sulla sponda sinistra si osservano quattro grandi marmitte, leggermente più a monte compaiono varie forme minori. Tutte queste forme giacciono in prossimità del livello del fiume e sono da considerare attive o, al massimo quiescenti. A quote più elevate, sulle pareti della forra si osservano numerose concavità ad asse verticale, che possono essere almeno in parte considerate come "paleomarmitte", quasi completamente smantellate dal progredire dell'erosione fluviale.

Le forme delle marmitte, anche durante le fasi iniziali del loro sviluppo, possono essere singole o raggruppate e, spesso, più marmitte si fondono fra loro. Nella forra di S. Lazzaro si osservano quasi ovunque forme minori, non ancora completamente sviluppate, di marmitte; gli esempi più numerosi e significativi e più facilmente raggiungibili, si trovano all'imbocco della gola, a monte del ponte di Diocleziano.

Durante le fasi di magra il Metauro scorre molto lentamente lungo la forra, dando quasi l’impressione di essere incapace di modellare ulteriormente il canyon. Durante le piene, invece, il livello dell’acqua aumenta talvolta anche di oltre 10 m e la corrente si fa impetuosa: è proprio in queste fasi che il Metauro esprime tutta la sua irruenza e forza erosiva, dimostrando con l’intenso mulinare dei vortici, spumeggiare e rimontare di grandi onde che la forra è viva e viene tuttora attivamente erosa.

LOG:

Puoi loggare immediatamente ed inviarmi le risposte in seguito.

Ricorda: se non invii le risposte entro un periodo di tempo accettabile il tuo log verrà cancellato senza preavviso.

Domande:

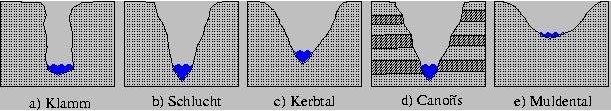

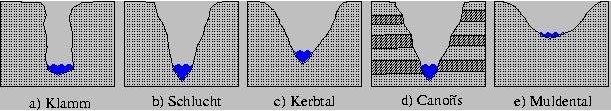

- Le valli fluviali sono suddivise in varie tipologie come per esempio:

a) Forra o orrido

b) Gola

c) Valle a V

d) Canyon

e) Valle a U

In base al grado di presenza dei seguenti fenomeni:

- Erosione in profondità (incisione)

- Erosione laterale (meandri)

- Denudazione sui versanti

Quale tra questi fenomeni è il più significativo in una forra?

-

Tipicamente le marmitte dei giganti nascono dall'erosione fluviale nelle località che erano ricoperte da ghiacciai. Secondo te (aiutati con la descrizione della cache) c’era anche qui un ghiacciaio che ha inciso la forra? Argomenta la tua risposta.

-

Al WP1, guardando giù dal ponte, puoi vedere delle grosse marmitte. Stima la lora grandezza. Secondo te sono paleomarmitte o sono ancora vive?

-

Al WP2 trovi un pannello informativo. Nella sezione “Carta d’identità” si legge: «Il fiume [...] Metauro, il più lungo corso d’acqua della regione Marche coi suoi XX km di lunghezza ed un bacino idrografico di YYYY chilometri quadrati». XX e YYYY?

-

Al WP3 (raggiungible solo quando il fiume non è in piena), guardandoti attorno puoi farti un’idea delle rocce che costituiscono la forra. Qui ci sono anche rocce stratificate inclinate. Che tipo di rocce sono secondo te? Misurane l’inclinazione (non scordarti a casa il goniometro! ;-) ).

-

Per raggiungere il WP3 hai incontrato qualche marmitta? Se si in che grado di evoluzione (es: giovani, vive, morte/paleomarmitte)? Pensa anche allo schema di Fig. 3.

-

Aggiungi una foto di te col tuo GPS ed una marmitta.

|

The giants' kettles of the Metauro River |

|

The Gorge of San Lazzaro

Along the valley between Calmazzo and Fossombrone, the Metauro River cuts across the ridge of the Monti della Cesana. This mountains are made up of calcareous-selcifying and calcareous-marly rocks of the Jurassic upper-Eocene age (Majolica formations, Marne a Fucoidi, Scaglia Bianca and Scaglia Rossa). The valley floor of the considered valley section is occupied by a relict alluvial plain, relatively large and hanging on the active riverbed (terrace with upper Pleistocene deposits). The current riverbed of the Metauro River is therefore more or less sunken within this plain, from which it is separated by steep escarpments of varying height from 5-6 m to over 25 m.

At S. Lazzaro di Fossombrone, in the stretch where the riverbed meets the whitish selciferous limestones of the formation of Majolica, particularly resistant to erosion, the slopes are very close and their height reaches almost 30 m. The Metauro River begins here to flow for about 500 m on a narrow and suggestive gorge with overhanging walls, whose width at river level does not exceed 13.5 m. The water are quite deep, with peaks higher than 17 m. The gorge is crossed by the a bridge called “Ponte dei Saltelli” or “Ponte di Diocleziano”. The bridge allows a superb view from above both of the gorge and of the giant's kettle on the left bank of the river.

Fig.1: Geological section of the Gorge of S. Lazzaro

Fig.1: Geological section of the Gorge of S. Lazzaro

The formation of the Gorge of S. Lazzaro, as we see it today, dates back to the Holocene because it is an active form that affects the upper Pleistocene terrace. The surface of this terrace, which corresponds more or less to the actual Fossombrone-Calmazzo roadway, in fact indicates the highest position reached by the Metauro riverbed during the last glacial period (Pleistocene sup.), Between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago . The alluvial gravels of the terrace cover and level a rocky substratum with an extremely irregular surface, furrowed by numerous buried depressions. One of these depressions, of shape and size comparable to those of the current gorge, represents an ancient bed of the Metauro river buried by alluvial sediments. During its evolutionary history, in the considered valley section, the Metauro river has therefore repeatedly carved and filled gorges in the Maiolica limestone.

In Fig.2 we can see a hypothesis on the birth and evolution of the Gorges of S. Lazzaro:

- Riss-Wurm - beginning of Wurm: primitive stream of water that started to carve the rock until the Rupestrian Limestone;

- Wurm inf. - medium: the rocky substratum is covered by the expansion of the Fosso di S. Lazzaro conoid;

- Wurm sup. - Holocene: the tectonic activity instead of sedimentation, determines the creation of another gorge parallel to the buried one.

Fig.2: Hypothesis on the origin and evolution of the Gorges of S. Lazzaro

Fig.2: Hypothesis on the origin and evolution of the Gorges of S. Lazzaro

The giants' kettles

The slopes of the gorge carved near S. Lazzaro di Fossombrone by the Metauro River in the calcareous limestone of the Maiolica formation present splendid examples of particular forms of river erosion, the so-called "giants' kettles". These forms, also known as giants’ cauldrons, moulin potholes, or simply potholes, have been drilled by the whirling erosion of the river stream. These are typically sub-cylindrical holes whose diameter and depth vary from a few centimeters to several meters. The potholes are the dominant form of river erosion in very narrow riverbeds and in the presence, even occasional, of very fast and turbulent water flows. The whirling movement of water, in contact with the bottom or with the walls of the fluvial channels, twirls small pebbles which exert abrasive action (Fig.3―1). The insistence of vortices in the same point can create small concavities, which form the embryos of the potholes, inside of them the pebbles can be trapped (Fig.3―2). These pebbles twirl pushed by the whirling movement of the river stream, brush the walls of the concavities and, thus accentuating the action of drilling, gradually increase the size of the pothole itself (Fig.3―3).

Fig.3: Pothole formation diagram

Fig.3: Pothole formation diagram

The process continues until the form is extinguished, with the opening of holes in the walls or for an excessive deepening that traps too many pebbles and/or too heavy pebbles, making the whirling action ineffective. Erosion is not always able to produce potholes, but often produces concavities and cracks of various shapes and sizes, which are generally associated with real pots.

In the case of the Gorge of S. Lazzaro, the potholes are particularly well developed under the Saltelli or Diocleziano bridge. Here the potholes was born and preserved thanks to the hardness of the Maiolica limestone and the high speed and turbulence of the water stream when the river is in flood. On the left bank there are four larger potholes, slightly further upstream there are various smaller kettles. All these formations lie near the river level and are to be considered active or at most quiescent. At higher altitudes, on the walls of the gorge, numerous concavities with vertical axis can be observed, which may at least partly be considered as old potholes, almost completely destroyed by the river erosion.

The shape of the potholes, even during the initial stages of their development, can be single or grouped and, often, more kettles can merge together to a single bigger one. In the gorge of S. Lazzaro, potholes not yet fully developed are observed almost everywhere; the most numerous and significant and most easily accessible examples are at the mouth of the gorge, upstream from the Diocletian bridge.

When the Metauro river is in low water the stream flows very slowly along the gorge, giving the impression of being unable to further model the canyon. During the floods, however, the water level sometimes increases even more than 10 m and the stream is impetuous: it is precisely in these phases that the Metauro expresses all its impetuousness and erosive force, demonstrating with the intense milling of the vortices, foaming and reassembling large waves that the gorge is alive and is still actively eroded.

LOGGING:

You can log immediately and send to me the answers to the below questions later.

Remember: your log will be deleted without notice if you don’t send any answer in an acceptable time frame.

Questions:

- The river valleys are divided into various types such as:

a) Ravine

b) Gorge

c) V-shaped valley

d) Canyon

e) U-shaped valley

According with the presence and intensity of the following phenomenon:

- Erosion in depth (degradation)

- Lateral erosion

- Denudation on the slopes

Which phenomenon is the most significant in a gorge?

-

Typically the giants' kettles are formed by a river erosion in places that were covered by glaciers. Do you think (read also the cache description) that there was also here a glacier that modelled the gorge? Explain your answer.

-

At WP1, looking down from the bridge, you can see some big potholes. Estimate their size. Are they dead or still alive?

-

At WP2 you will find an info panel. The "Carta d’identità" section says: «Il fiume [...] Metauro, il più lungo corso d’acqua della regione Marche coi suoi XX km di lunghezza ed un bacino idrografico di YYYY chilometri quadrati». XX and YYYY?

-

At WP3 (reachable only when river not in flood), looking around you can get an idea of the rocks of the gorge. Here there are also inclined stratified rocks. What kind of rocks arethey? Measure the inclination (don’t forget your own goniometer! ;-) ).

-

Did you meet any pothole while walking towards WP3? If yes, what degree of evolution are they in (ex: young, alive, dead)? Think also about the scheme of Fig. 3.

-

Add a picture of yourself, your GPS and a pothole.

Fonti/Resources: