This educational field puzzle cache is one of four Princeton Battlefield puzzle caches. Its recommended to complete the four field puzzles first, as all these cache final locations are in nearby Institute Woods property.

The American victory at the Battle of Princeton (January 3, 1777) was one of the most consequential of the American Revolution. George Washington and his soldiers marched north from Trenton and attacked a British force south of the town. Washington's victory bolstered American morale and provided great confidence to his soldiers.

On January 3, 1777, the peaceful winter fields and woods of Princeton Battlefield were transformed into the site of what is considered to be the fiercest fight of its size during the American Revolution. During this desperate battle, American troops under General George Washington surprised and defeated a force of British Regulars. Coming at the end of "The Ten Crucial Days" which saw the well-known night crossing of the Delaware River and two battles in Trenton, the Battle of Princeton gave Washington his first victory against the British Regulars on the field. The battle extended over a mile away to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Washington escaped from one enemy to attack another at Princeton

Despite their success in repulsing several frontal attacks at the Battle of Assunpink Creek (Battle of Second Trenton) on January 2, 1777, Gen. George Washington and his senior officers were filled with a sense of dread. Gen. Charles Cornwallis’ army of 8,000 veteran soldiers were poised to deliver a punishing blow the following morning. The fact that the British had discovered a ford that led to the vulnerable American right flank made the American position on the Assunpink Creek near Trenton all the more dangerous.

“Washington's night time plan to quietly march from Trenton to Princeton"

“Washington's night time plan to quietly march from Trenton to Princeton"

Rather than risk defeat in Trenton, Washington, in collaboration with his senior officers, agreed upon a bold and dangerous plan. That very night the Continental army would quietly leave its positions along the creek and march east, then north towards Princeton. With deceptive campfires still burning along the creek, Washington’s intrepid soldiers began their 18-mile march through the dark and bitterly cold night. By stealing a march on Cornwallis, Washington retained the all-important initiative and avoided any movement that smacked of retreat. Washington’s successful night march on January 2 and 3, 1777 is remembered as one of the great flank marches in American history.

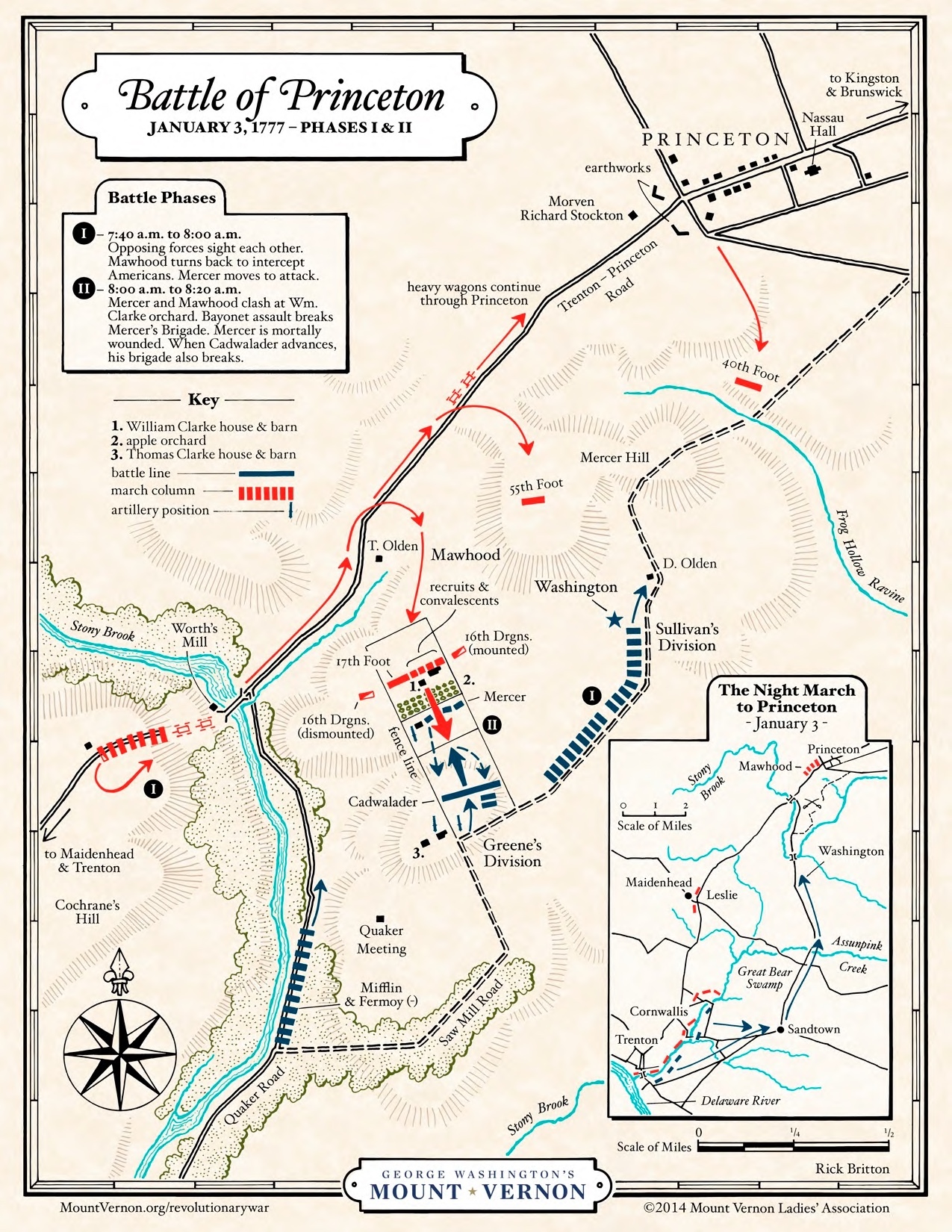

“Battle of Princeton from Trenton Phase I & II"

“Battle of Princeton from Trenton Phase I & II"

Opposing forces almost missed one another

>Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood, the British officer in command at Princeton, had been ordered by Cornwallis to bring reinforcements down to his position at Trenton. Leaving a small garrison in Princeton, Mawhood began his march down the Post Road towards Trenton just after dawn. Washington’s northward marching army was primarily traveling on a parallel and lesser-known road that crossed the Thomas Clark Farm – a road that was largely out of view from the Post Road. Behind schedule, Washington sent a small detachment under the command of Hugh Mercer to seize and destroy the Stony Brook bridge along the Post Road. It was this detachment that was viewed by scouts attached to Mawhood’s column. Mawhood, now aware of a new threat near Princeton, wheeled his force about and approached Mercer on the Clarke Farm.

One might imagine what would have occurred if this chance meeting had not occurred. Mawhood would have been well on his way to Trenton and Washington would have found but a small, vulnerable garrison at Princeton.

Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood rode into battle with springer spaniels at his side

Mercer’s American force soon beheld the advance of soldiers from two British regiments – the 17th and 55th Foot. Mawhood himself could soon be seen atop his “brown pony” and with a pair of his favorite spaniels bounding at his side. As David Hackett Fischer writes, “[Mawhood] delighted in the display of a highly developed air of nonchalance, especially on the field of battle.” Despite this strangely casual display, Mawhood was a veteran and highly capable officer who would more than prove his mettle on the fields at Princeton.

Many British soldiers believed they had killed Gen. Washington during the battle

“Mercer was bayonetted "

“Mercer was bayonetted "

During the opening phases of the battle, a bayonet charge by the British forces broke Hugh Mercer’s American line near an orchard fence line on the Clarke Farm. Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer, a friend of the Washingtons and a resident of Fredericksburg, Virginia, attempted to reform his command, but was soon surrounded by angry British regulars shouting “Surrender you damn rebel!” Mercer, a veteran of European wars and a fierce patriot, refused to lay down his arms. After a brief struggle, Mercer was bayonetted repeatedly and left for dead. Given that Mercer was well-attired (as opposed to the rags worn by most American soldiers), a high-ranking officer, and refused to surrender, many British soldiers believed they had killed Washington himself.

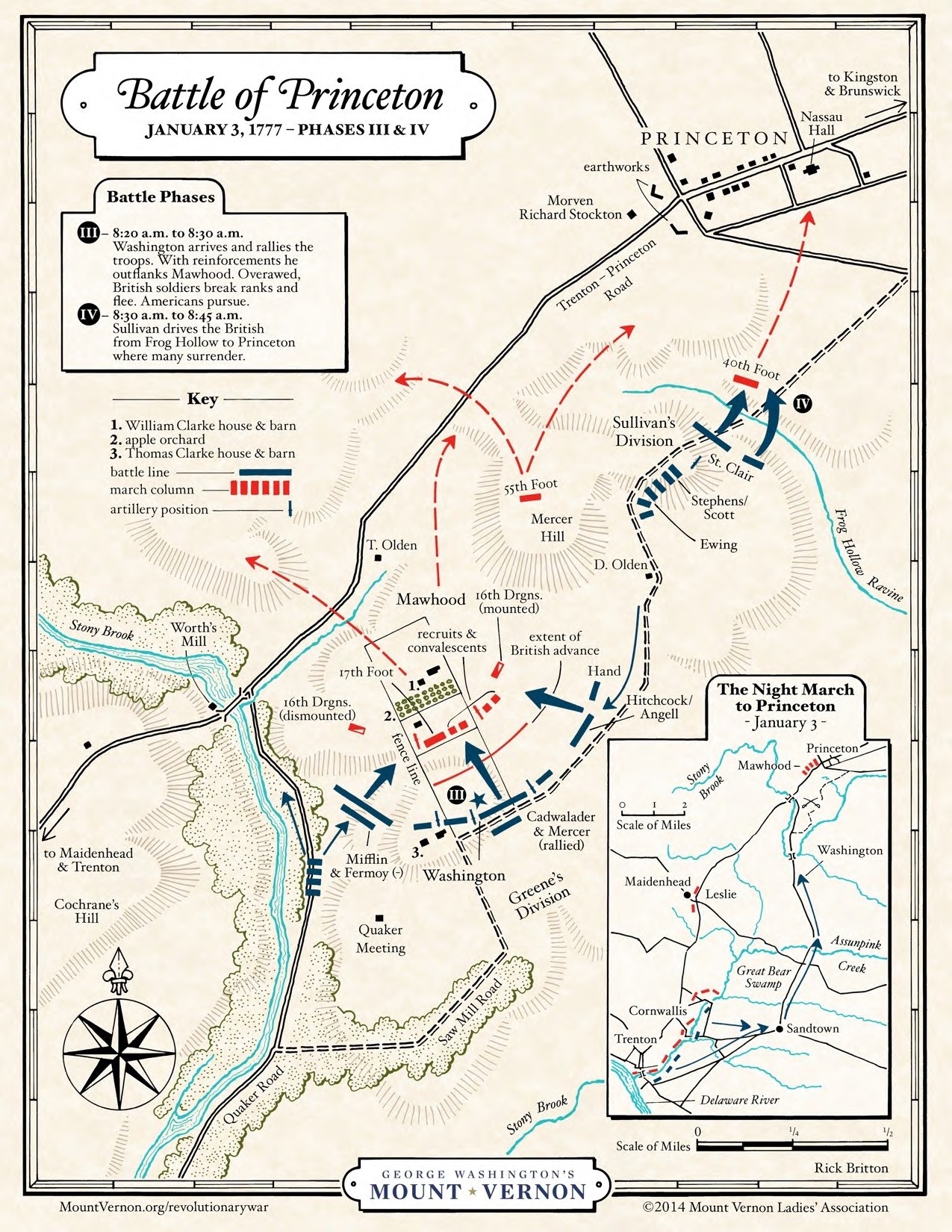

“Parade with us my brave fellows"

“Parade with us my brave fellows"

At one point, Washington was just 30 yards from the British line

Moving to reinforce Mercer’s broken line Cadwalader’s brigade of Pennsylvania militia, Delaware and Philadelphia light infantry, and a small unit of marines – all told about 1,500 men - moved towards the British. Despite their numerical superiority, the inexperienced Americans began to fall back under the steady fire from the British regulars. As Cadwalader reformed his line, up rode Washington astride a magnificent white horse. Amidst the flying musket balls, Washington coolly assured his soldiers, “Parade with us my brave fellows"! There is but a handful of the enemy and we shall have them directly!” Washington then proceeded to lead the militiamen forward from the front. He at one point was only 30 yards from the British line – easy musket range.

“Parade with us my brave fellows"

“Parade with us my brave fellows"

John Fitzgerald, one of Washington’s officers, reportedly pulled his hat over his eyes, expecting to see the General shot from the saddle at any moment. Before removing it moments later to see Washington wreathed in smoke but unscathed and still in full command.Despite his proximity, Washington remained uninjured and his galvanizing presence stabilized the American line at a critical moment in the battle. Soon Washington, along with fresh reinforcements, were chasing the remnants of Mawhood’s broken force through the fields and woods.

Marines fought alongside Washington at Princeton

After his arrival upon the Pennsylvania shore of the Delaware River, Washington sent out an urgent plea for reinforcement. One of the first contingents of soldiers to respond to this request were roughly 600 marines from the Philadelphia area. This force of marines had been recruited for duty aboard the various Continental warships now anchored near Philadelphia and were generally considered to be excellent fighters. The marine officers had seen active duty against the British onboard various vessels and their men had been occupied in daily drill and frequent skirmishes with British forces operating in the area.

Three companies of marines accompanied Washington’s army on its nighttime march to Princeton. Moving with Cadwalader’s Brigade into the fight, a few marines under the command of Major Samuel Nicholas, engaged Manhood’s troops on the Clarke Farm. During the fierce fighting the Regulars several of the marines were killed in battle, including Captain William Shippin. These casualties were some of the first to be suffered by marines on any battlefield.

“Battle of Princeton Phase III & IV"

“Battle of Princeton Phase III & IV"

The final actions of the battle occurred on the Princeton campus

After the American victory on the Clarke Farm, the final military actions of the Battle of Princeton shifted towards the town itself. Roughly 200 British Regulars had fortified Nassau Hall at the center of what is Princeton University today. From this stout building, the British intended to use firing positions to hold off the Americans until a relief party arrived. The Americans positioned cannon around the building and soon began firing on the building and its occupants. Legend has it that one of the American cannonballs decapitated the portrait of King George II hanging inside the building – a fearful omen that further spurred the British garrison to surrender.

The victory at Princeton rescued the Patriot cause from one of its darkest hours

The disastrous defeats in the 1776 New York Campaign and the precipitous retreat across the Delaware River had left the prospects for American independence in tatters. Rather than retreat to winter quarters as most on both sides of the Delaware River expected, Washington chose to attack in the dead of winter. Washington’s victories at Trenton, Assunpink Creek, and at Princeton completely reversed the fortunes of the Continental Army and the prospects for the young United States. Washington’s victories and the effective guerrilla war waged in the New Jersey countryside forced Sir William Howe to retract the British lines back towards New York City - giving up much of the Jersey countryside that had been captured earlier.

Many look at the battles of Trenton and Princeton as small affairs, but these battles, combined with the tough winter campaigning sliced Howe’s once mighty army in half. Howe’s further requests for reinforcement left many in London aghast.

Washington’s bold gambles and effective leadership had delivered the very sort of public confidence that Washington was keen to produce. Not only were the British and the Loyalists discouraged, but his own soldiers found newfound confidence that they could beat the very best that the British could put into the field.

”Bar Code Puzzle"

The posted coordinates take you the the "The Site of Moulder's Battery PLAQUE" where you will use your smart phone to scan the bar code to watch the video and find answers on the plaque for the following clues;

N40 19. AB W074 40.CD

The Video Clues

A = "What year was Letter from the Officer?"

1776 = (6) 1780 = (3) 1777 = (5)

B = How many men attacked Princeton by Daylight?

500 = (21) 300 = (32) 1000 = (27)

C = On the Plaque, Moulder's Battery consisted of boys from where?

New York = (1) New Jersey = (2) Philadelphia = (0)

D = What year did Artist James Peale illustrate the painting on the plaque?

1778 = (15) 1780 = (10) #1784 = (02)

This cache is one of "The American Revolution Geo~Trail" caches throughout New Jersey. These special geocaches are hidden at many historic locations which have a connection to important New Jersey's American Revolutionary War history. To participate in the optional Geo-Trail, after you find the geocache, locate the secret code and record it into your passport which you will print from this website. Information at njpatriots.org

”njpatriots.org"

”njpatriots.org"

The Northern New Jersey Cachers, NNJC is about promoting a quality caching experience in Northern New Jersey. For information on The Northern New Jersey Cachers group you can visit: www.nnjc.org.

nnjc.org & metrogathering.org, & njpatriots.org

nnjc.org & metrogathering.org, & njpatriots.org