Richard H. Jahns: True American Rock Star

This Earth Cache is dedicated to Professor Richard H. Jahns,1915-1983...

Beloved teacher, legendary field geologist, world expert on pegmatites, and humorist.

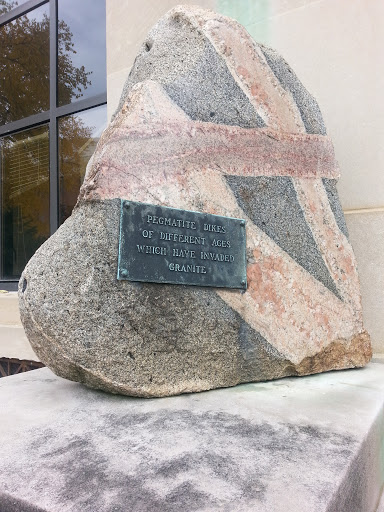

Here you will find some large slabs of Chelmsford Grey Granite Pegmatite from the Fletcher Quarry in Massachusetts. You'll need to observe these amazing rocks to claim credit for the cache (see below), but first... a little about the man himself. A more thorough biography can be found in the 1986 Memorial Issue of American Mineralogist.

Richard Henry Jahns, distinguished Fellow of the Society, passed away on New Year's Eve, December 31, 1983, at the age of 68. At the time of his death, he was Dean Emeritus of the School of Earth Sciences and Welton J. and Maud L'Anphere Crook Professor of Geology and Applied Earth Sciences at Stanford University. Dick will long be remembered in the fields of mineralogy and petrology for his fundamental contributions to the understanding of granitic pegmatites. Dick also made significant scientific contributions in other areas of the earth sciences, including engineering geology, the geology of southern California, the glacial geology of New England, economic geology, and earthquake hazards. His early work also involved studies of the stratigraphy and mammalian fauna of the Ventura Basin, California. Such diversity is quite rare in any scientist, but Dick Jahns was indeed a rare breed of scientist and human being. In addition to being an internationally respected and highly productive scientist with widely ranging interests, he was also a superb educator and administrator who helped shape the modern approach to earth science education and who served as Dean of colleges of earth sciences at two major U.S. universities over a twenty-year period. During the last decade of his career, he became increasingly involved in public policy decision making in areas such as earthquake safety and land use planning.

Richard Henry Jahns, distinguished Fellow of the Society, passed away on New Year's Eve, December 31, 1983, at the age of 68. At the time of his death, he was Dean Emeritus of the School of Earth Sciences and Welton J. and Maud L'Anphere Crook Professor of Geology and Applied Earth Sciences at Stanford University. Dick will long be remembered in the fields of mineralogy and petrology for his fundamental contributions to the understanding of granitic pegmatites. Dick also made significant scientific contributions in other areas of the earth sciences, including engineering geology, the geology of southern California, the glacial geology of New England, economic geology, and earthquake hazards. His early work also involved studies of the stratigraphy and mammalian fauna of the Ventura Basin, California. Such diversity is quite rare in any scientist, but Dick Jahns was indeed a rare breed of scientist and human being. In addition to being an internationally respected and highly productive scientist with widely ranging interests, he was also a superb educator and administrator who helped shape the modern approach to earth science education and who served as Dean of colleges of earth sciences at two major U.S. universities over a twenty-year period. During the last decade of his career, he became increasingly involved in public policy decision making in areas such as earthquake safety and land use planning.

What is Pegmatite?... the simple version

Pegmatites are extreme igneous rocks that form during the final stage of a magma’s crystallization. They are extreme because they contain exceptionally large crystals and they sometimes contain minerals that are rarely found in other types of rocks. To be called a “pegmatite,” a rock should be composed almost entirely of crystals that are at least one centimeter in diameter. The name “pegmatite” has nothing to do with the mineral composition of the rock. Most pegmatites have a composition that is similar to granite with abundant quartz, feldspar, and mica. These are sometimes called “granite pegmatites” to indicate their mineralogical composition. However, compositions such as “gabbro pegmatite,” “syenite pegmatite,” and any other plutonic rock name combined with “pegmatite” are possible. Complex pegmatites commonly contain tourmaline, lepidolite, topaz, cassiterite, fluorite, beryl, etc. Pegmatites are not rare rocks, but their overall volume is small. They form small marginal parts of large magma intrusions known as batholiths.

Large crystals in igneous rocks are usually attributed to a slow rate of crystallization. However, with pegmatites, large crystals are attributed to low-viscosity fluids that allow ions to be very mobile. During the early states of a magma’s crystallization, the melt usually contains a significant amount of dissolved water and other volatiles such as chlorine, fluorine, and carbon dioxide. Water is not removed from the melt during the early crystallization process, so its concentration in the melt grows as crystallization progresses. Eventually there is an overabundance of water, and pockets of water separate from the melt. These pockets of superheated water are extremely rich in dissolved ions. The ions in the water are much more mobile than ions in the melt. This allows them to move about freely and form crystals rapidly. This is why crystals of a pegmatite grow so large. Unusual minerals form because the fluid is enriched in exotic chemical elements like lithium, boron, beryllium, rare earth elements, etc. These elements are forced to form their own mineral phases because they are rejected by major rock-forming minerals like quartz, feldspar, and others.

What is Pegmatite?... the Richard Jahns version

These holocrystalline rocks are typically characterized by extreme variations in grain size, ranging from very coarse "giant" crystals to fine groundmass crystals, and have as their major constituents minerals commonly found in ordinary igneous rocks. Minor constituents of granitic pegmatites can include a variety of unusual minerals; some of the latter are of economic importance, and these provided much of the impetus for the early study of pegmatites in the United States. The estimated bulk composition of many granitic pegmatites corresponds to thermally low parts of the quaternary haplogranite system NaAlSi3O8- KAlSi3O8-SiO2-H2O.

These rocks have a wide age distribution, occurring in host rocks ranging in age from 3900 Ma (metamorphosed Precambrian Greenland shield rocks) to 20 Ma (rocks of the Alpine orogenic belts). As examples, the pegmatites in the Black Hills of South Dakota and most of the pegmatites of Colorado and New Mexico are of Precambrian age (1800-1600 Ma), whereas the well-known southern California pegmatites are hosted by Mesozoic (190-100 Ma) granitic to gabbroic rocks of the Southern California batholith. Granitic pegmatites are associated with many different rock types, including migmatites, metamorphic rocks ranging from granulites to greenschists, and igneous rocks ranging from gabbros to granites. Variation in the estimated depth of formation of granitic pegmatites has been used as the basis for a simple but useful, fourfold classification: greater than 11 km (pegmatites associated with granulites of shield areas); between 7 and 11 km (mica-bearing pegmatites commonly associated with metamorphic rocks of the almandine-amphibolite facies); between 3.5 and 7 km ("rare-element" pegmatites commonly associated with metamorphic rocks of the cordierite-amphibolite facies); and between 1.5 and 3.5 km (pegmatites that contain miarolitic cavities or "pockets" and that are commonly associated with granites or low-grade metamorphic rocks). Granitic pegmatites occur in a variety of shapes and sizes, ranging from veins several centimeters across to large tabular bodies tens of square kilometers in outcrop area. Jahns often stated that the average shape of granitic pegmatites is "about like a lima bean."

Many granitic pegmatite bodies are internally zoned, either symmetrically or asymmetrically, with respect to mineralogy, texture, and element distribution. It is the internal segregation of granitic pegmatites that has stimulated much of the pegmatite research since 1960, including that of Dick Jahns. The most important genetic controversy in pegmatite formation theory has involved igneous versus metamorphic origins for some of the deeper-seated pegmatites, that grade into migmatites. Most of the North American pegmatite specialists belong to the igneous camp; however, in certain cases, metamorphic origins, involving recrystallization, anatexis, or replacement, are clearly indicated by field relations and compositional data. Refinements of these genetic models have been primarily based on experimental work involving volatilecontaining silicate melts; development and application of equilibrium thermodynamic models derived from these experimental results; analytical studies of element-zonation patterns within and around pegmatite bodies; and the application of phase equilibria and mineral, fluid-inclusion, and stable isotope geothermometry and geobarometry.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Logging requirements:

(You can log your find as soon as the email is sent, but logs with insufficient answer may be deleted)

Send me a note through my caching profile with:

1. The text "GC Rock Star" on the first line

2. The number of people in your group (put in the log as well).

3. Take a look at the large slabs containing the pegmatite. How wide are the veins?

4. Look at the individual crystals. Are they large or small? Describe the largest individual crystals you see.

5. What colors do you see in the pegmatite? What does that tell you about its mineral make-up? Why? Would you consider this rare or regular?

6. Optional (yet encouraged) Post a photo of you and your party being Rock Stars!

| I have earned GSA's highest level: |

|

Sources:

Jahns Memorial Issue, American Mineralogist 1986, Volume 71

Pegmatite Basics at SandAtlas.org and Geology.com