Megali Grava - Die Höhle von Loutses

Korfu besteht wie viele Inseln im Mittelmeer zu großen Teilen aus Kalkstein. Die Geomorphologie ist entsprechend durch schroffe Felslandschaften und Karstlandschaften geprägt.

Das nördliche Bergland

Das nördliche Bergland nimmt den gesamten Norden der Insel ein. Der Ostteil wird durch das Kalkmassiv des Pantokrators (906 m) gebildet. Diese mesozoischen Kalke reichen nach Westen als ausgeprägter Rücken bis nach Trompeta. Während es sich bei den Ablagerungen im Nordosten um Flysch-Schichten handelt, wird der Nordwesten aus molassischen Kalken und Mergeln des Miozän und Pliozän gebildet. An die Gebirgszone schließt sich nach Norden eine alluviale Küstenebene an. In dem sich nach Westen anschließenden Küstenbereich erstrecken sich die pliozänen Mergel wieder bis ans Meer. Von hier reichen sie dann bis zur Westküste, wo sie teilweise Kliffküsten bilden. Die Unterschiedlichkeit der Gesteine spiegelt sich auch in der Oberflächengestalt deutlich wider. So fällt das Pantokratormassiv steil zum Osten und Süden hin ab. Auf dem Massiv des Pantokrators befindet sich ein Plateau mit deutlichen Verkarstungserscheinungen, während der eigentliche Gipfel am Ostrand des Plateaus kegelförmig ca. 100 m herausragt. Im Gegensatz dazu stehen die Teile südlich davon. Diese sind hauptsächlich aus miozänen Kalkbrekzien gebildet. Es überwiegen schroffe Formen und an der Küste steile, manchmal sogar überhängende Kliffs. Die pliozänen Gebiete des Nordwestens sind dem mergeligen Material entsprechend hügelig mit weichen Formen und Höhen zwischen 100 und 200 m Höhe.

Nördliches Bergland

Die Höhle von Loutses

Die Höhle befindet sich am nördlichen Rand des Pandokratormassiv. Sie ist eine typische Karsthöhle. Sie befindet sich in der Nähe des Dorfes Loutses am Pantokrator. Am Ende des Dorfes Loutses gibt es einen Abzweig nach links mit der Aufschrift „Cave“. Fährt man diesen bis zum Ende, erreicht man eine kleine Parkmöglichkeit. Dort führt ein Weg direkt zur Höhle hinab. Hier ist festes Schuhwerk nötig, da der Weg sehr steil nach unten führt. Die Höhle besteht aus einem flachen Boden, sowie einer sehr schönen Decke mit Tropfsteinen. Es ist ein erhebendes Gefühl, dort zu stehen.

Verkarstung und Höhlenentstehung

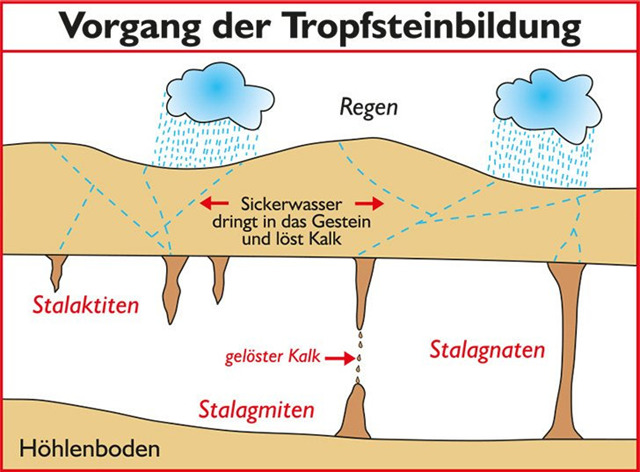

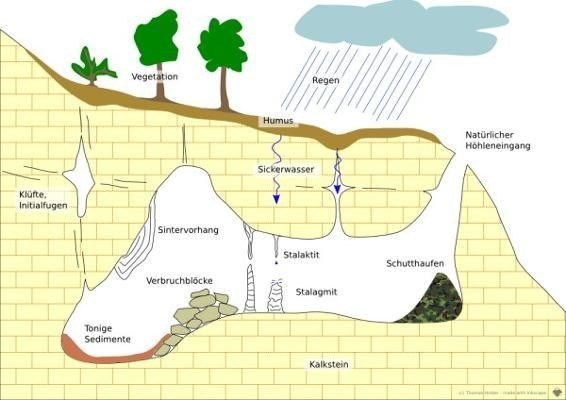

Voraussetzung für die Bildung von Tropfsteinhöhlen ist ein hoher Gehalt an gelösten Mineralien – in der Regel Kalk – im Wasser, die sich in der Höhle ablagern. Kalk ist in saurem Wasser löslich. Versickerndes Regenwasser besitzt die notwendige Säure in Form von Kohlensäure. Sie ist aus der Reaktion des Wassers mit dem Gas Kohlendioxid aus der Luft entstanden. Das Wasser dringt durch Klüfte in den Boden ein und bahnt sich fortan unterirdisch seinen Weg, bis es entfernt wieder an das Tageslicht kommt. Damit eine Karsthöhle entstehen kann, braucht es wasserlösliches Gestein mit einer gewissen Anzahl Klüfte oder Spalten, Wasser und einen Höhenunterschied zwischen der Eintritt- und Austrittsstelle des Wasserlaufes. Nach vielen Jahren werden die Spalten im Gestein größer. Sobald sie eine gewisse Größe erreicht haben, bildet das Wasser einen Wirbel und kann den Kalk wesentlich schneller lösen. Dann hilft auch die Erosion mit: eingeschwemmter Sand und andere Sedimente schleifen die Wände wie Sandpapier ab. Es entstehen unterirdische Hohlräume. An der Decke dieser Hohlräume können sich Tropfsteine bilden. Sie sind Ausfällungen von Calcit (CaCO3). Wenn das im Gestein nach abwärts sickernde und mit gelöstem Kalk gesättigte Wasser an der Höhlendecke tropfenweise austritt, gibt es CO2 an die Höhlenluft ab und kann daher nicht mehr so viel Kalk in Lösung halten wie vorher. Das überschüssige Calciumcarbonat wird daraufhin an der Austrittsstelle des Wassers in Form des Minerals Calcit ausgefällt. Wiederholte Ausfällungen an derselben Stelle der Höhlendecke erzeugen einen Calcitzapfen (Stalaktit), welcher ähnlich wie ein Eiszapfen wächst, da das kalkhaltige Wasser an ihm herunterläuft. Der Durchmesser und die Form des Stalaktiten hängt vom Kalkgehalt und der Wassermenge ab. Kommt nur sehr wenig Wasser oder hat es einen sehr geringen Kalkgehalt, wird der Kalk bevorzugt nahe der Decke abgelagert und der Stalaktit bekommt eine gedrungene Form. Steht viel Wasser zur Verfügung, wird über den gesamten Stalaktiten Kalk abgelagert und er wird deutlich schlanker. Stalaktiten sind immer deutlich schlanker, als Stalagmiten und laufen nach unten dünn aus. Sie sind sehr gerade und weisen keine Verdickungen auf. Vom Ende des Stalaktiten tropft das Wasser auf den Höhlenboden. Die Erschütterung beim Aufschlag des Tropfens bewirkt eine weitere Freisetzung von CO2, wodurch auch am Höhlenboden Calcimcarbonat ausgefällt wird. Langzeitliche Wiederholung des Vorgangs an derselben Stelle führt zum Aufbau eines meist steilen Calcitkegels (Stalagmit). Stalagmiten können auch mit Stalaktiten zu einer Tropfsteinsäule (Stalagnat) zusammenwachsen. Das Material, das die Tropfsteine formt, nennt man Sinter.

Abb. https://www.afrika.de

Abb. https://hoehlen.sonnenbuehl.de

Beantwortet bitte folgende Fragen, um den Earthcache loggen zu können:

- Messe/Schätze die Höhe, Breite und Tiefe der Höhle!

- In der Höhle gibt es Tropfsteine. Welche Arten (Stalagtiten, Stalagmiten, Stalagnate) könnt Ihr in der Höhle entdecken?

- Aus welchem Grund sind nicht alle Arten hier zu finden?

- Betrachtet nun die Höhlendecke genauer. Welche Form haben die Tropfsteine? Sind sie lang und schmal oder haben sie eine eher gedrungene Form. Wie ist das zu erklären?

- Füge dem Logeintrag ein Foto von Dir, Deinem GPS oder Deinem Maskottchen vor oder in der Höhle bei.

Schickt eine Mail mit Euren Antworten an uns! Nach dem Absenden der Antworten könnt Ihr gleich loggen. Ihr braucht nicht unsere Logfreigabe abwarten! Falls etwas nicht in Ordnung ist, melden wir uns. Wir wünschen euch viel Spaß bei dieser geologischen Erkundung!

English version

Megali Grava - The Cave of Loutses

Like many Mediterranean islands, Corfu consists largely of limestone. The geomorphology is accordingly characterized by rugged rocky landscapes and karst landscapes.

The northern mountain country

The northern mountains cover the entire north of the island. The eastern part is formed by the limestone massif of the Pantokrator (906 m). These Mesozoic limestone reaches to the west as a pronounced ridge as far as Trompeta. While the deposits in the northeast are flysch layers, the northwest is formed from Molassian limestone and marls from the Miocene and Pliocene. An alluvial coastal plain joins the mountain zone to the north. In the coastal area adjoining to the west, the Pliocene marls extend back to the sea. From here they then extend to the west coast, where they partly form cliff coasts. The diversity of the rocks is also clearly reflected in the shape of the surface. The Pantocrator massif drops steeply to the east and south. On the Pantocrator massif there is a plateau with clear karstification phenomena, while the actual summit on the eastern edge of the plateau protrudes in a conical shape approx. 100 m. In contrast to this are the parts south of it. These are mainly formed from Miocene calcareous breccias. Craggy shapes predominate and steep, sometimes even overhanging cliffs on the coast. The Pliocene areas of the northwest are hilly according to the marly material with soft shapes and heights between 100 and 200 m.

The cave of loutses

The cave is located on the northern edge of the Pandocrator massif. It is a typical karst cave. It is located near the village of Loutses on the Pantokrator. At the end of the village of Loutses there is a branch to the left with the inscription "Cave". If you drive this to the end, you will reach a small parking space. There a path leads directly down to the cave. Sturdy shoes are necessary here, as the path leads down very steeply. The cave consists of a flat floor and a very nice ceiling with stalactites. It's an uplifting feeling to stand there.

Karstification and cave formation

The prerequisite for the formation of stalactite caves is a high content of dissolved minerals - usually lime - in the water, which are deposited in the cave. Lime is soluble in acidic water. Rainwater that seeps away has the necessary acidity in the form of carbonic acid. It was created from the reaction of water with the gas carbon dioxide in the air. The water penetrates through gaps into the ground and from then on paves its way underground until it comes back to daylight in a distance. In order for a karst cave to arise, it needs water-soluble rock with a certain number of crevices or gaps, water and a difference in height between the point of entry and exit of the watercourse. After many years the crevices in the rock get bigger. As soon as they have reached a certain size, the water forms a vortex and can dissolve the lime much faster. The erosion is helping: washed-in sand and other sediments grind the walls like sandpaper. There are underground cavities. Stalactites can form on the ceiling of these cavities. They are precipitates of calcite (CaCO3). When the water, which seeps down in the rock and is saturated with dissolved lime, escapes drop by drop from the cave ceiling, it releases CO2 into the cave air and can therefore no longer hold as much lime in solution as before. The excess calcium carbonate is then precipitated at the outlet point of the water in the form of the mineral calcite. Repeated precipitations in the same place on the cave ceiling produce a calcite cone (stalactite), which grows like an icicle, as the calcareous water runs down it. The diameter and shape of the stalactite depends on the lime content and the amount of water. If there is very small amount of water or if it has a very low amount of lime content, the lime is preferably deposited near the ceiling and the stalactite takes on a compact shape. If there is a lot of water available, lime is deposited over the entire stalactite and it becomes significantly thinner. Stalactites are always significantly slimmer than stalagmites and run thin towards the bottom. They are very straight and do not have any bulges. From the end of the stalactite, the water drips onto the cave floor. The vibration when the drop hits the ground causes a further release of CO2, which also causes calcium carbonate to precipitate on the cave floor. Long-term repetition of the process at the same point leads to the build-up of a mostly steep calcite cone (stalagmite). Stalagmites can also grow together with stalactites to form a dripstone column (stalagnate). The material that forms the dripstones is called sinter.

Please answer the following questions in order to log the Earthcache:

- Measure / guess the height, width and depth of the cave!

- There are dripstones in the cave. Which species (stalagmites, stalagtites, stalagnates) can you find in the cave?

- Why can’t all 3 types of dripstones be found in the cave? Please give reasons!

- Now take a closer look at the cave ceiling. What shape are the dripstones? Are they long and slim or are they more compact in shape? How can this be explained?

- Add a photo of you, your GPS or your mascot to the log entry in front of or in the cave.

Send us an email with your answers! After submitting the answers, you can log immediately. You don't need to wait for our response! If something is wrong, we will contact you. We wish you a lot of fun with this geological exploration!

Quellen: