The River Mekong

The Mekong is a trans-boundary river in Southeast Asia. It is the world’s 12th-longest river and the 7th-longest in Asia. Its estimated length is 4,350 km, and it drains an area of 795,000 km2, discharging 457 km3 of water annually.

From the Tibetan Plateau this river runs through China’s Yunnan province, Burma (Myanmar), Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

The extreme seasonal variations in flow and the presence of rapids and waterfalls in this river have made navigation difficult. The river is a major trading route linking China’s southwestern province of Yunnan to Laos, Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand to the south, an important trade route between western China and Southeast Asia.

The Mekong rises as the Lancang (Lantsang) in the “Three Rivers Area” on the Tibetan Plateau in the Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve. The reserve protects the headwaters of, from north to south, the Yellow (Huang He), the Yangtze and the Mekong Rivers. It flows southeast through Yunnan Province, and then through the Three Parallel Rivers Area in the Hengduan Mountains, along with the Yangtze to its north and the Salween River (Nujiang in Chinese) to its south.

The Mekong then meets the tripoint of China, Burma (Myanmar) and Laos. From there it flows southwest and forms the border of Burma and Laos for about 100 kilometres (62 mi) until it arrives at the tripoint of Burma, Laos, and Thailand. This is also the point of confluence between the Ruak River (which follows the Thai-Burma border) and the Mekong.

From the Golden Triangle tripoint, the Mekong turns southeast to briefly form the border of Laos with Thailand. It then turns east into the interior of Laos, flowing first east and then south for some 400 kilometres (250 mi) before meeting the border with Thailand again. Once more, it defines the Laos-Thailand border for some 850 kilometres (530 mi) as it flows first east, passing in front of the capital of Laos, Vientiane, then turns south. A second time, the river leaves the border and flows east into Laos soon passing the city of Pakse. Thereafter, it turns and runs more or less directly south, crossing into Cambodia.

At Phnom Penh the river is joined on the right bank by the river and lake system the Tonlé Sap. When the Mekong is low, the Tonle Sap is a tributary; water flows from the lake and river into the Mekong. When the Mekong floods, the flow reverses; the floodwaters of the Mekong flow up the Tonle Sap.

Immediately after the Sap River joins the Mekong by Phnom Penh, the Bassac River branches off the right (west) bank. The Bassac River is the first and main distributary of the Mekong; thus, this is the beginning of the Mekong Delta. The two rivers, the Bassac to the west and the Mekong to the east, enter Vietnam very soon after this. In Vietnam, the Bassac is called the Hậu River (Sông Hậu or Hậu Giang); the main, eastern, branch of the Mekong is called the Tiền River or Tiền Giang. In Vietnam, distributaries of the eastern (main, Mekong) branch include the Mỹ Tho River, the Ba Lai River, the Hàm Luông River, and the Cổ Chiên River.

Drainage Basin

The Mekong Basin can be divided into two parts: the ‘Upper Mekong Basin’ in Tibet and China, and the ‘Lower Mekong Basin’ from Yunnan downstream from China to the South China Sea. From the point where it rises to its mouth, the most precipitous drop in the Mekong occurs in Upper Mekong Basin, a stretch of some 2,200 km (1,400 mi). Here, it drops 4,500 metres (14,800 ft) before it enters the Lower Basin where the borders of Thailand, Laos, China and Burma (Myanmar) come together in the Golden Triangle. Downstream from the Golden Triangle, the river flows for a further 2,600 km (1,600 mi) through Laos, Thailand and Cambodia before entering the South China Sea via a complex delta system in Vietnam.

Upper Mekong Basin

The Upper Basin makes up 24% of the total area and contributes 15 to 20% of the water that flows into the Mekong River. The catchment here is steep and narrow. Soil erosion has been a major problem and approximately 50% of the sediment in the river comes from the Upper Basin.

In Yunnan province in China, the river and its tributaries are confined by narrow, deep gorges. The tributary river systems in this part of the basin are small. Only 14 have catchment areas that exceed 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi), yet the greatest amount of loss of forest cover in the entire river system per square kilometer has occurred in this region due to heavy unchecked demand for natural resources. In the south of Yunnan, in Simao and Xishuangbanna Prefectures, the river changes as the valley opens out, the floodplain becomes wider, and the river becomes wider and slower.

Lower Mekong Basin

Major tributary systems develop in the Lower Basin. These systems can be separated into two groups: tributaries that contribute to the major wet season flows, and tributaries that drain low relief regions of lower rainfall. The first group are left bank tributaries that drain the high-rainfall areas of Lao PDR. The second group are those on the right bank, mainly the Mun and Chi rivers, that drain a large part of Northeast Thailand.

Laos lies almost entirely within the Lower Mekong Basin. Its climate, landscape and land use are the major factors shaping the hydrology of the river. The mountainous landscape means that only 16% of the country is farmed under lowland terrace or upland shifting cultivation. With upland shifting agriculture (slash and burn), soils recover within 10 to 20 years but the vegetation does not. Shifting cultivation is common in the uplands of Northern Laos and is reported to account for as much as 27% of the total land under rice cultivation. As elsewhere in the basin, forest cover has been steadily reduced during the last three decades by shifting agriculture and permanent agriculture. The cumulative impacts of these activities on the river regime have not been measured. However, the hydrological impacts of land-cover changes induced by the Vietnam War were quantified in two sub-catchments of the Lower Mekong River Basin.

Loss of forest cover in the Thai areas of the Lower Basin has been the highest in all the Lower Mekong countries over the past 60 years. On the Korat Plateau, which includes the Mun and Chi tributary systems, forest cover was reduced from 42% in 1961 to 13% in 1993. Although this part of Northeast Thailand has an annual rainfall of more than 1,000 mm, a high evaporation rate means it is classified as a semi arid region. Consequently, although the Mun and Chi Basins drain 15% of the entire Mekong Basin, they only contribute 6% of the average annual flow. Sandy and saline soils are the most common soil types, which makes much of the land unsuitable for wet rice cultivation. In spite of poor fertility, however, agriculture is intensive. Glutinous rice, maize and cassava are the principal crops. Drought is by far the major hydrological hazard in this region.

Mekong Geology

The internal drainage patterns of the Mekong are unusual when compared to those of other large rivers. Most large river systems that drain the interiors of continents, such as the Amazon, Congo, and Mississippi, have relatively simple dendritic tributary networks that resemble a branching tree.

Typically, such patterns develop in basins with gentle slopes where the underlying geological structure is fairly homogenous and stable, exerting little or no control on river morphology. In marked contrast, the tributary networks of the Salween, Yangtze, and particularly the Mekong, are complex with different sub-basins often exhibiting different, and distinct, drainage patterns. These complex drainage systems have developed in a setting where the underlying geological structure is heterogeneous and active, and is the major factor controlling the course of rivers and the landscapes they carve out.

The elevation of the Tibetan Plateau during the Tertiary period was an important factor in the genesis of the south-west monsoon, which is the dominant climatic control influencing the hydrology of the Mekong Basin. Understanding the nature and timing of the elevation of Tibet (and the Central Highlands of Viet Nam) therefore helps explain the provenance of sediment reaching the delta and the Tonle Sap Great Lake today. Studies of the provenance of sediments in the Mekong Delta reveal a major switch in the source of sediments about eight million years ago (Ma). From 36 to 8 Ma the bulk (76%) of the sediments deposited in the delta came from erosion of the bedrock in the Three Rivers Area. From 8 Ma to the present, however, the contribution from the Three Rivers Area fell to 40%, while that from the Central Highlands rose from 11 to 51%. One of the most striking conclusions of provenance studies is the small contribution of sediment from the other parts of the Mekong Basin, notably the Khorat Plateau, the uplands of northern Lao PDR and northern Thailand, and the mountain ranges south of the Three Rivers Area.

The last glacial period came to an abrupt end about 19,000 years ago (ka) when sea levels rose rapidly, reaching a maximum of about 4.5 m above present levels in the early Holocene at about 8 ka. At this time the shoreline of the South China Sea almost reached Phnom Penh and cores recovered from near Angkor Borei contained sediments deposited under the influence of tides, and salt marsh and mangrove swamp deposits. Sediments deposited in the Tonle Sap Great Lake about this time (7.9–7.3 ka) also show indications of marine influence, suggesting a connection to the South China Sea. Although the hydraulic relationships between the Mekong and the Tonle Sap Great Lake systems during the Holocene are not well understood, it is clear that between 9,000 and 7,500 years ago the confluence of the Tonle Sap and the Mekong was in close proximity to the South China Sea.

The present river morphology of the Mekong Delta developed over the last 6,000 years. During this period, the delta advanced 200 km over the continental shelf of the South China Sea, covering an area of more than 62,500 km2. From 5.3 to 3.5 ka the delta advanced across a broad embayment formed between higher ground near the Cambodian border and uplands north of Ho Chi Minh City. During this phase of its development the delta was sheltered from the wave action of long-shore currents and was constructed largely through fluvial and tidal processes. At this time the delta was advancing at a rate of 17–18 m per year. After 3.5 ka, however, the delta had built out beyond the embayment and became subject to wave action and marine currents. These deflected deposition south-eastwards in the direction of the Cà Mau Peninsula, which is one of the most recent features of the delta.

For much of its length the Mekong flows through bedrock channels, i.e. channels that are confined or constrained by bedrock or old alluvium in the bed and riverbanks. Geomorphologic features normally associated with the alluvial stretches of mature rivers, such as meanders, oxbow lakes, cut-offs, and extensive floodplains are restricted to a short stretch of the mainstream around Vientiane and downstream of Kratie where the river develops alluvial channels that are free of control exerted by the underlying bedrock.

The Mekong Basin is not normally considered a seismically active area as much of the basin is underlain by the relatively stable continental block. Nonetheless, the parts of the basin in northern Laos, northern Thailand, Burma (Myanmar) and China do experience frequent earthquakes and tremors. The magnitude of these earthquakes rarely exceeds 6.5 on the Richter scale and is unlikely to cause material damage.

Source: www.geologypage.com/2014/05/mekong-river.html

Waterfall Geology

Waterfall, area where flowing river water drops abruptly and nearly vertically. Waterfalls represent major interruptions in river flow. Under most circumstances, rivers tend to smooth out irregularities in their flow by processes oferosion and deposition. In time, the long profile of a river (the graph of its gradient) takes the form of a smooth curve, steepest toward the source, gentlest toward the mouth. Waterfalls interrupt this curve, and their presence is a measure of the progress of erosion. A waterfall may also be termed a falls or sometimes a cataract, the latter designation being most common when large volumes of water are involved. Waterfalls of small height and lesser steepness are called cascades; this term is often applied to a series of small falls along a river. Still gentler reaches of rivers that nonetheless exhibit turbulent flow and white water in response to a local increase in channel gradient are called rapids.

The highest waterfall in the world is Angel Falls in Venezuela (807 m [2,650 feet]). Arguably the largest waterfall is the Khone Falls on the Mekong River in Laos: the volume of water passing over it has been estimated at 11,600 cubic m (410,000 cubic feet) per second, although its height is only 70 m (230 feet).

There are several conditions that give rise to waterfalls. One of the most common reasons for a waterfall’s existence is difference in rock type. Rivers cross many lithological boundaries, and, if a river passes from a resistant rock bed to a softer one, it is likely to erode the soft rock more quickly and steepen its gradient at the junction between the rock types. This situation can occur as a river cuts and exhumes a junction between different rock beds. The riverbed of Niagara Falls, which forms part of the boundary between the United States and Canada, has a blocky dolomite cap overlying a series of weaker shales and sandstones.

A related cause of waterfalls is the presence of bars of hard rock in the riverbed. A series of cataracts has been created on the Nile where the river has worn its bed sufficiently to uncover the hard crystalline basement rock.

Erosion and geology are not the only factors that create waterfalls. Tectonic movement along a fault may bring hard and soft rocks together and encourage the establishment of a waterfall. A drop in sea level promotes increased downcutting and the retreat upstream of a knickpoint (sharp change of gradient indicating the change of a river’s base-level). Depending on the change of sea level, river flow, and geology (among other factors), falls or rapids may develop at the knickpoint. Many waterfalls have been created by glaciation where valleys have been over-deepened by ice and tributary valleys have been left high up on steep valley sides.

Within a river’s time scale, a waterfall is a temporary feature that is eventually worn away. The rapidity of erosion depends on the height of a given waterfall, its volume of flow, the type and structure of rocks involved, and other factors. In some cases the site of the waterfall migrates upstream by headward erosion of the cliff or scarp, while in others erosion may tend to act downward, to bevel the entire reach of the river containing the falls. With the passage of time, by either or both of these means, the inescapable tendency of rivers is to eliminate any waterfall that may have formed. The energy of rivers is directed toward the achievement of a relatively smooth, concave upward, longitudinal profile.

Even in the absence of entrained rock debris, which serve as an erosive tool of rivers, the energy available for erosion at the base of a waterfall is great. One of the characteristic features associated with waterfalls of any great magnitude, with respect to volume of flow as well as to height, is the presence of a plunge pool, a basin that is scoured out of the river channel beneath the falling water. In some instances the depth of a plunge pool may nearly equal the height of the cliff causing the falls. Plunge pools eventually cause the collapse of the cliff face and the retreat of the waterfall. Retreat of waterfalls is a pronounced feature in some places.

Source: www.britannica.com/place/Khone-Falls

There are the different types or classifications of waterfalls:

• Block – Water descends from a relatively wide stream or river.

• Cascade - Water descends a series of rock steps.

• Cataract - A very large and powerful waterfall.

• Fan – Water spreads horizontally as it descends while remaining in contact with bedrock.

• Horsetail – Descending water maintains some contact with bedrock.

• Chute: A large quantity of water forced through a narrow, vertical passage.

• Plunge - Water descends vertically, losing contact with the bedrock surface.

• Punchbowl – Water descends in a constricted form, then spreads out in a wider pool.

• Segmented – Distinctly separate flows of water form as it descends.

• Tiered – Water drops in a series of distinct steps or falls

• Multi-step - A series of waterfalls one after another of roughly the same size each with its own sunken plunge pool.

The Mekong Waterfalls

Khon Phapheng Waterfalls (Mainland) & Somphamit / Liphi Waterfalls (Don Khone)

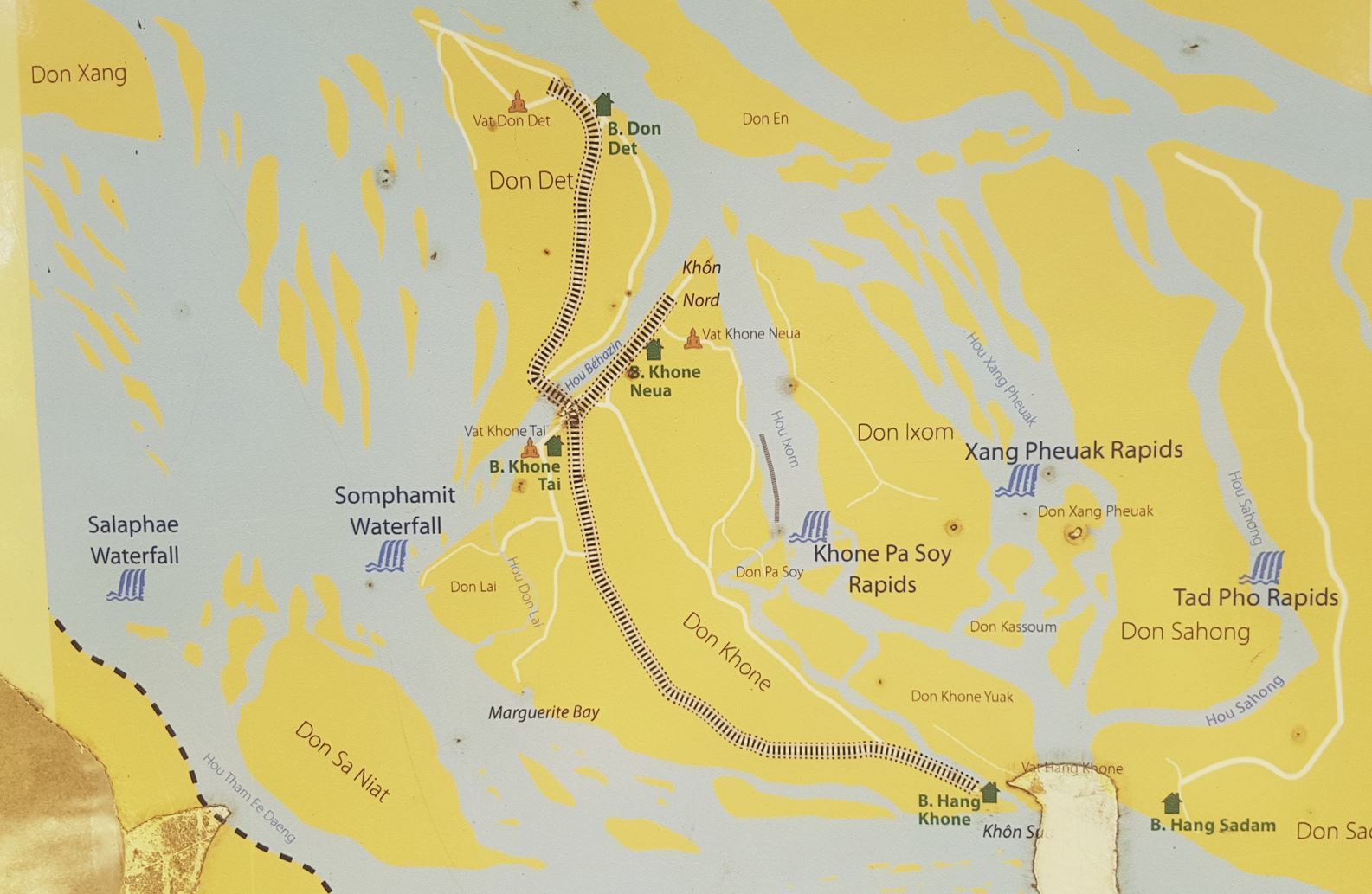

Near the border with Cambodia, the Khon Phapheng Falls (or the "big falls") are the largest in southeast Asia and they are the main reason that the Mekong is not fully navigable from Cambodia into China. The highest falls reach to 21 meters, and the succession of rapids stretch 9.7 km of the river's length. In the late 19th century French colonialists made repeated attempts to navigate the falls but their efforts failed. This difficulty led to the construction of the Don Det / Don Khon narrow gauge railway. The railway was a 7-kilometre (4.3 mi)-long railway on the islands of Don Det and Don Khon, part of the Ssi Phan Don (Four Thousand Islands) archipelageo in Champasak Province of southern Laos. Built by the Mekong Exploration Commissioning, the railway was operated by the Lao State Railway. It opened in 1893, and closed in 1940 or 1949. The railway facilitated the transportation of vessels, freight and passengers along the Mekong River. The Don Det–Don Khon islands railway was the only railway built, opened and operated in Laos until 2009, when a line was opened between Nong Khai in Thailand and the Thanaleng railway station in Dongphosy (near Vientiane).

Log Requirements

Send the answers to following questions to me via e-mail or messanger. You don't have to wait for my answer. In case of something is wrong, I will get in contact with you.

1) What is the name of the Natural Nature Reserve where the Mekong rises?

2) How long defines the Mekong the border between Laos and Thailand (km)?

3) What was the main source of sediments 36 to 8 million years ago?

4) Beside geology and erosion which important factor is responsible for encouraging the establishment of a waterfall?

5) When you look at the waterfall from the platform at the header coordinates, which type/classification of waterfall do you see and explain with your own words how it developed.

6) Make a photo from the header coordinates with the waterfall in the background with you and/or your GPS?