WMT #13: Holey Post? No More Commons!

The cache, a small, camo-taped, screw-capped pot, is hidden just off a corner of the trail as it starts the descent back down to the starting point.

Next to the cache is a tall vertical gritstone with a large hole through the top - an old gate post. Such posts which may have one (as here) or more holes either passing completely or partially through the stone are a familiar sight in the countryside throughout the UK. Many are very old and may well be over 300 years old.

Gateposts usually last a remarkably long time - partly because they need to be installed securely and strong enough to support heavy gates and more recently because they are used as tensioning points for fences.

Traditionally the materials used would have been whatever was available, strong and affordable, so in the days of cheap labour stone was often the obvious choice. In order to be effective a stone gatepost would have to be sunk deep into the ground and ways of attaching fences and gates were necessary.

Traditionally the materials used would have been whatever was available, strong and affordable, so in the days of cheap labour stone was often the obvious choice. In order to be effective a stone gatepost would have to be sunk deep into the ground and ways of attaching fences and gates were necessary.

Commonly, stone gateposts had a couple of holes in them which carry the hinges for a swinging gate. These allow a gate to be opened more easily and avoid the need to lift the weight of the gate.

A relatively rare arrangement is where the gatepost has several holes drilled out to take the horizontal rails of the gate - these are sometimes called 'heave gates' for obvious reasons. This arrangement totally avoids the need for hinges but only works where there the horizontal holes are deep enough for the gate to be moved enough to one side to release the rails from the similar gatepost at the other side.

of the gate - these are sometimes called 'heave gates' for obvious reasons. This arrangement totally avoids the need for hinges but only works where there the horizontal holes are deep enough for the gate to be moved enough to one side to release the rails from the similar gatepost at the other side.

Old stone gateposts with only one hole (as here) are more difficult to explain. This photoblog has the following (albeit difficult to comprehend!) explanation for the arrangement used to support such a gate . . .

'Anciently, the Gates in the Peak Hundreds were formed and hung without any iron-work, even nails, as I have been told; and some yet remain in Birchover and other places, where no iron-work is used in the hanging: a large mortise-hole is made thro’ the hanging-post, perpendicular to the plane of the Gate, at about four feet and a half high, into which a stout piece of wood is firmly wedged, and projects about twelve inches before the Post; and in this piece of wood, two augur holes are made, to receive the two ends of a tough piece of green Ash or Sallow, which loosely embraces the top of the head of the Gate (formed to a round), in the bow so formed : the bottom of the head of the Gate is formed to a blunt point, which works in a hole made in a stone, set fast in the ground, close to the face of the Post. It is easy to see, by the mortise-holes in all old Gate-Stoops, that this mode of hanging Gates was once general'.

General View of the Agriculture of Derbyshire (Vol 2. 1813) by John Farey Snr

Mineral Surveyor of Upper Crown Street, Westminster.

At least it is clear that iron latches and hinges were later additions to stone gate posts. Other materials used for gateposts are metal and wood. Metal is becoming fairly standard on farms as it has a high strength to weight ratio and can be very flexible in what is attached to it - but it is always susceptible to rust especially at the base even when galvanised.

In this modern era, a well functioning gate is assumed to be a good thing – guarding property, keeping out vagrants and cold callers. But this notion of privately controlled land is fairly new.

In this modern era, a well functioning gate is assumed to be a good thing – guarding property, keeping out vagrants and cold callers. But this notion of privately controlled land is fairly new.

See here and here for a couple of fascinating photoblogs about similar gate posts in Derbyshire, one of which also provides some interesting background on the history and development of (agricultural) land ownership - with progressive enclosure of commons* over centuries (see link below) necessitating the installation of boundary walls/fences and (often locked) access gates. This has sadly deprived most of the British people of access to most agricultural land.

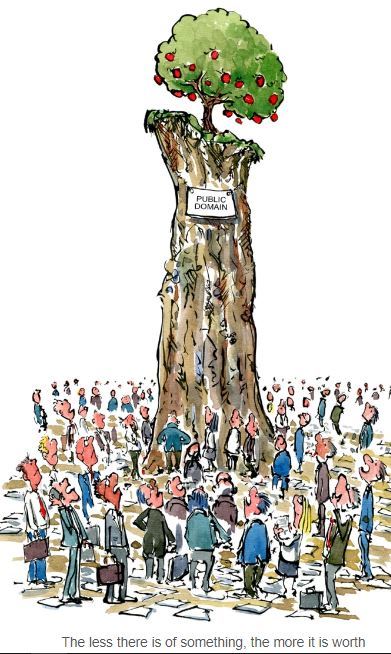

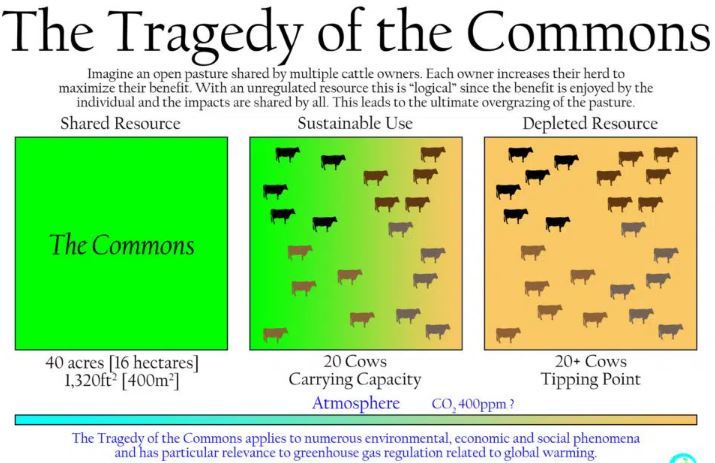

*land or resources belonging to or affecting the whole community.

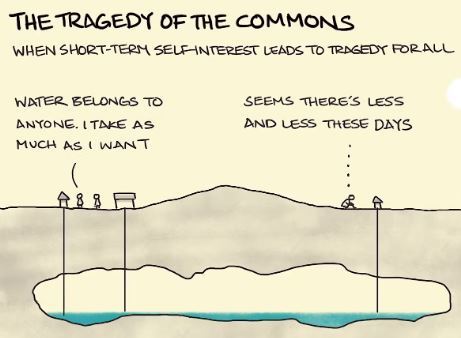

See here for an explanation of the Tragedy of the Commons - 'a metaphoric label for a concept widely discussed in economics, ecology and other sciences, the widespread application of which has had a fundamental - and mostly detrimental - effect on society and the environment.

According to the concept, if numerous independent individuals enjoy unlimited access to a finite, valuable resource. eg. a pasture, they will tend to overuse it, and may end up by destroying its value altogether. To exercise voluntary restraint is not a rational choice for any one individual - if he did, the others would merely supplant him - yet the predictable result is a tragedy for all.

In other words . . . The Tragedy of the Commons 'describes the conflict between short-term self-interest and long-term common good. It proposes that self-interested decisions made by the rational individual are almost guaranteed to cause detriment to the well-being of the wider community. These decisions allow the individual to benefit themselves whilst simultaneously distributing the adverse effects on the larger population. Often this leads to [serious] social and environmental problems'.

The openness of social networks enables creativity but invites exploitation

Fortunately, something can (indeed must) be done about it . . . see here and here for short explanatory videos of the issue and possible solutions

'Far from being profoundly destructive, we humans have deep capacities for sharing resources with generosity and foresight' (from The Miracle of the Commons, in Aeon 4 May 2021).