English version below

Die große Kristallfrage

Mitten auf dem BTU-Gelände in Senftenberg steht ein unscheinbarer Granitstein. Bei näherer Betrachtung mag man auf den ersten Blick nichts Spektakuläres erkennen. Doch wenn man die Zusammensetzung der Minerale überprüft, die Größe der Kristalle der einzelnen Minerale betrachtet und sie mit dem aktuellen Wissensstand über die Kristallbildung vergleicht, kann man einige interessante Schlüsse ziehen. Dabei stoßen wir auf das faszinierende Frage bezüglich der Größe des Kristalls.

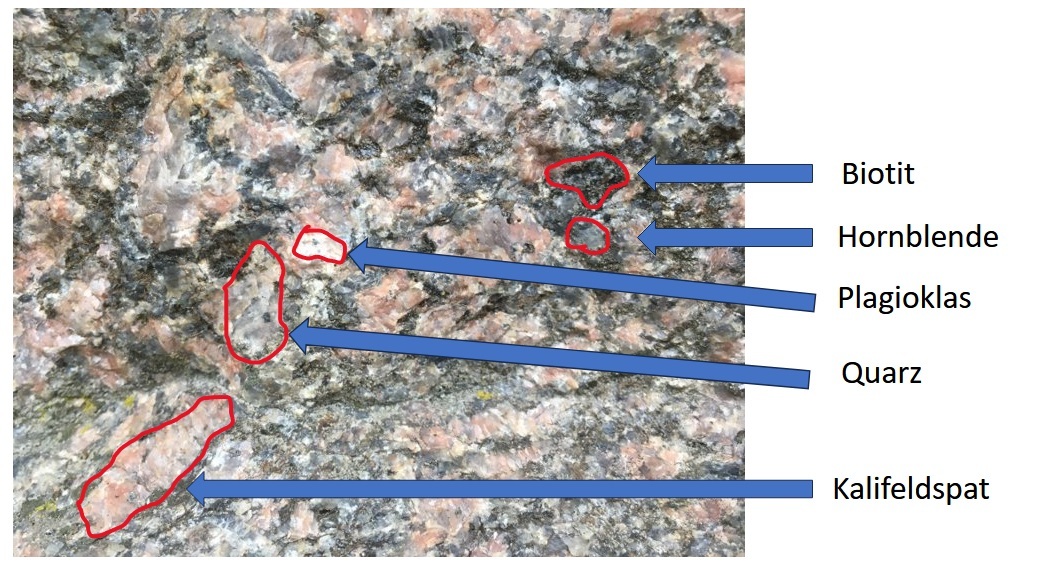

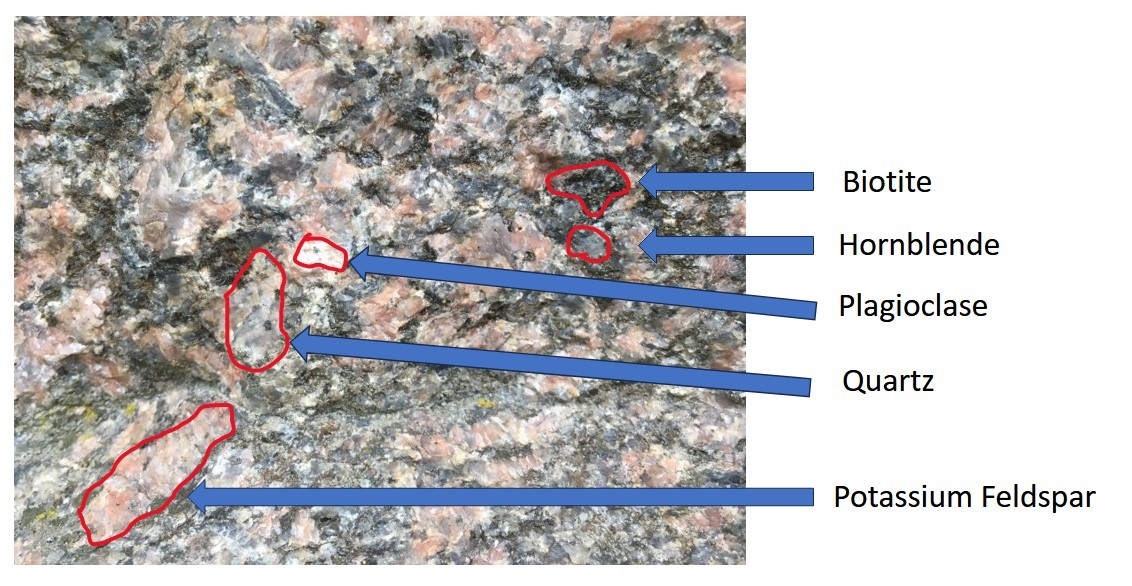

Mineralische Zusammensetzung unseres Gesteins

Leider gibt es keine Informationen über das Gestein auf dem BTU-Gelände. Um die mineralische Zusammensetzung zu bestimmen, müssen detaillierte Beobachtungen gemacht werden. Da es sich um plutonisches Gestein handelt, das lange Zeit unter der Erdoberfläche festgeworden ist, können wir mit bloßem Auge die Kristalle der einzelnen Mineralien erkennen. Da das Magma lange Zeit abkühlte, hatten die Kristalle viel Zeit zum Wachsen. Vielleicht sogar Millionen von Jahren.

Wie bilden sich Kristalle in plutonischem Gestein?

Das flüssige Magma, das sich unter der Erdoberfläche befindet, hat eine relativ hohe Temperatur. Wenn die Temperatur sinkt, beginnen sich im Magma Kristalle zu bilden. Jedes Mineral hat eine andere Kristallisationstemperatur. Unter Laborbedingungen war es möglich, die Kristallisationstemperatur einzelner Mineralien zu bestimmen. Der kanadische Wissenschaftler Norman Levi Bowen führte vor mehr als einem Jahrhundert eine Reihe von Experimenten durch und stellte zum ersten Mal die Reihenfolge der Kristallisation von Magmamineralen fest. Der Bowen'sche Reaktionszyklus findet auch heute noch Anwendung und ermöglicht es uns, die Bedingungen zu bestimmen, unter denen magmatische Gesteine entstanden sind. Je länger eine bestimmte Temperatur aufrechterhalten wird, desto mehr Zeit haben die entsprechenden Kristalle zum Wachsen.

Quelle: Open Geology

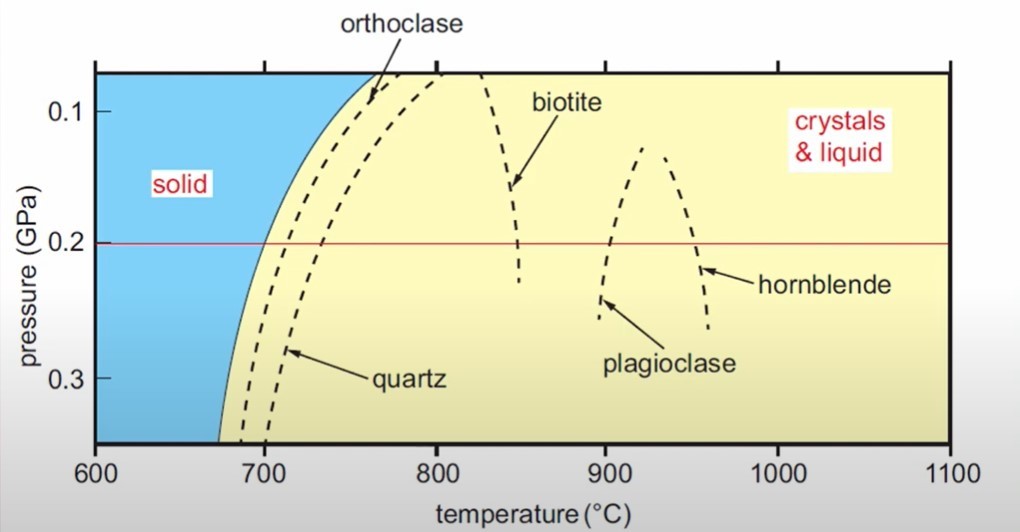

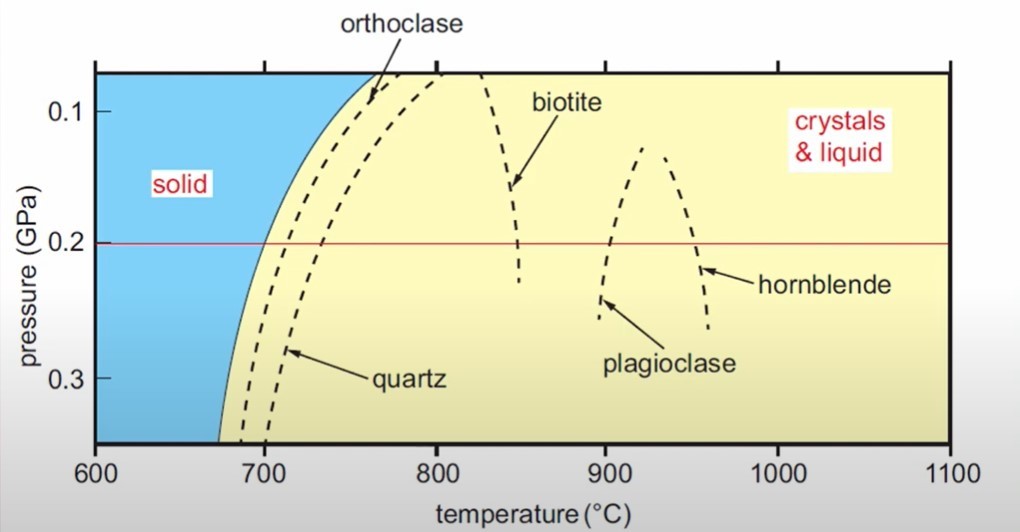

Ein weiteres wichtiges Hilfsmittel für Geologen sind die so genannten Phasendiagramme, die uns bereits genauer zeigen, unter welchen Bedingungen die Kristallisation von Mineralien stattfindet. Nachstehend füge ich ein Phasendiagramm für die Mineralien bei, aus denen unser BTU-Campusstein besteht.

Quelle: Geology at Cowbridge - Phasediagram for Shap granite minerals.

Das Phasendiagramm berücksichtigt nicht nur die Temperatur, sondern auch den Druck, der ebenfalls die Kristallisation beeinflusst. Da tief unter der Erde ein hoher Druck herrscht, muss auch ein entsprechend hoher Druck berücksichtigt werden. Das obige Phasendiagramm und die folgende Tabelle wurden von britischen Geologen für den so genannten Shap-Granit entwickelt, der eine sehr ähnliche Zusammensetzung wie unser BTU-Granit hat. In Tabellenform sieht die Kristallisationstemperatur wie folgt aus:

| Reihenfolge der Kristallisation |

|

Kristallisationstemperatur für Druck von 0,2 GPa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fragen:

1. Schau Dir die Kristalle des Steins im BTU-Innenhof genau an und betrachte dabei die mineralische Zusammensetzung unseres Gesteins. Bestimme die Reihnfolge der Größe von Kristallen vom kleinsten zum größten?

2. Die Kristalle welches Minerals sind die größten? Betrachte den Stein von allen Seiten. Wie groß ist der größte Kristall?

3. Welche Schlussfolgerungen können wir unter Berücksichtigung der Kristallisationstemperatur aus unserer Beobachtung ziehen? Unter welchen Bedingungen entstanden die größten Kristalle?

Quellen:

Michael D. Higgins, Geological Society, London, Special Publications Volume 168 Pages 207 - 219, Origin of megacrysts in granitoids by textural coarsening: a crystal size distribution (CSD) study of microcline in the Cathedral Peak Granodiorite, Sierra Nevada, California

https://www.youtube.com/@geologyatcowbridge5674/featured

https://de.geologyscience.com/geology/bowens-reaction-series

The Question of Big Crystal

There is an, at first glance, unremarkable granite stone in the middle of the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg (BTU) campus in Senftenberg. The casual eye might not see anything spectacular. But if you examine the composition of the minerals, look at the size of each mineral's crystals, and compare them with current knowledge about crystal formation, you can draw some interesting conclusions. By closer inspecting this granite stone we will come across the fascinating question regarding the crystal size.

Mineral composition of our rock

Unfortunately, there is no information about the rock on the BTU campus. To determine the mineral composition, detailed observations must be made. Because it is plutonic rock that has been solidified beneath the earth's surface for a long time, we can see the crystals of the individual minerals with the naked eye. Because the magma took a long time to cool, the crystals had plenty of time to grow. Maybe even millions of years.

How do crystals form in plutonic rocks?

The liquid magma that lies beneath the Earth's surface has a relatively high temperature. As the temperature drops, crystals begin to form in the magma. Every mineral has a different crystallization temperature. Under laboratory conditions it was possible to determine the crystallization temperature of individual minerals. Canadian scientist Norman Levi Bowen conducted a series of experiments more than a century ago and established for the first time the order of crystallization of magma minerals. Bowen's reaction cycle is still used today and allows us to determine the conditions under which igneous rocks were formed. The longer a certain temperature is maintained, the more time the corresponding crystals have to grow.

Source: Open Geology

Another important tool used by geologists are the so-called phase diagrams, which show us in more detail the conditions under which the crystallization of minerals takes place. Below I am including a phase diagram for the minerals that make up our BTU campus stone.

Source: Geology at Cowbridge - Phasediagram for Shap granite minerals.

The phase diagram takes into account not only the temperature, but also the pressure, which also influences crystallization. Since there is high pressure deep underground, a correspondingly high pressure must also be taken into account. The phase diagram and table below were developed by British geologists for what is known as Shap granite, which has a very similar composition to our BTU granite. In tabular form, the crystallization temperature looks like this:

| The crystallisation order |

|

Crystallization temperature for pressure of 0,2 GPa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Questions:

1. Look closely at the various crystals of the stone located on the BTU campus courtyard and consider its mineral composition. Determine the order of size of the crystals from smallest to largest?

2. Which mineral's crystals are the largest? Look at the stone from all sides. What size expressed in centimeres is the largest crystal you have found?

3. Taking the crystallization temperature into account, what conclusions can you draw from your observations? Under what conditions did the largest crystals form?

Sources:

Michael D. Higgins, Geological Society, London, Special Publications Volume 168 Pages 207 - 219, Origin of megacrysts in granitoids by textural coarsening: a crystal size distribution (CSD) study of microcline in the Cathedral Peak Granodiorite, Sierra Nevada, California

https://www.youtube.com/@geologyatcowbridge5674/featured

https://de.geologyscience.com/geology/bowens-reaction-series