For this EarthCache, you will be visiting Kitch-iti-kipi, also known as The Big Spring. Previous visits DO NOT COUNT! Your visit to Kitch-iti-kipi must be after the published date of this EarthCache. If you have visitied Kitch-iti-kipi in the past, GREAT! I'm sure you will be looking forward to another visit.

LOGGING REQUIREMENTS

In order to log this EarthCache, send me your answers to the following questions either through email or messaging from my profile page.

1(a): Look into the spring. Can you see clouds of dirt rising above the bottom of the spring?

1(b): What is causing these clouds of dirt?

2(a): Describe the color of the bottom of the spring.

2(b): What gives it this color?

3: Post a pic of you or a signature item either on the raft or with the raft in the background.

WHY HERE?

Kitch-iti-kipi is Michigan's largest natural freshwater spring. It is located in Palms Book State Park, a recreation passport is required for entry. There is an ADA-accessible, paved path from the parking lot to the observation deck and dock. The raft is ADA-accessible, too. The raft is O-shaped with a glass section in the center of the deck. From this center observation spot or from the sides of the raft, you can see the large trout swimming below, ancient tree trunks, lime-encrusted branches and clouds of sand pushed up by the bubbling water. It is a window into nature you will long remember.

LEGEND HAS IT...

Various legends about Kitch-iti-kipi have been handed down through the ages. One of the most popular legends claims that Kitch-iti-kipi was the name of a young Native American chieftain who resided in the region. Kitch-iti-kipi fell in love with a beautiful dark-haired maiden he spotted dancing near his birchbark wigwam. She insisted that he prove his devotion to her above all others by setting sail in his canoe out on The Big Spring and catching her in his arms as she leapt from an overhanging conifer bough.

Kitch-iti-kipi complied, taking his canoe across the frigid water, his eyes searching the treetops for his ladylove. Tragically, his canoe overturned, throwing Kitch-ti-kipi into the icy depths, never again to return to the surface. All the while, the story goes, the beautiful girl was in her village laughing with the other maidens about the chieftain’s foolish attempt to win her heart. The Big Spring was named Kitch-iti-kipi in honor of the young chieftain who went to his death in search of love.

It was also said that the indigenous people would travel to the spring in search of a name for their newborn child. The soon-to-be parents listened to the bubbling waters in order to the names the magical waters whispered to them. Still other tales claim that the spring has special healing powers.

HOW KITCH-ITI-KIPI CAME TO BE

Around 375 million years ago, during the Siurain Period, a warm clear sea covered what we now call Michigan.

Clear streams brought lime water to the sea where myriads of shelled creatures lived and died. Where they lived, the sea floor looked like a vast underwater garden. Clams, snails, and other shelled creatures lived, swam, fed, and died among the corals. All took lime from the water to build their shells and when they died the shells fell to the sea floor and mingled with lime muds chemically precipitated and together built up hundreds of feet, layer upon layer, of soft lime muds.

The Silurian seas withdrew, but other seas followed and other sediments were deposited on top of the Silurian

muds. Pressure compacted the muds to stone. The Silurian muds became limestones in which pressure and compaction

caused vertical cracks or joints. Each layer or stratum of mud became separated from the layers above and

below by a plane surface or horizontal crack and to the whole mass compacted into a stratified formation that sloped gently southward under the Lower Peninsula.

Millions of years later a great glacier filled with groundup rock debris spread over the area and in places

carved great grooves in the limestone. When the glacier melted it left the rock, clay, sand, and boulders, the glacial drift, plastered over the area. Ponding of the glacial melt waters made a lake that covered the Upper Peninsula. Nature started to fill the glacial lake with sediments, and spread layers of sand and clay on its floor. The ice left. The glacial lakes retreated into the basins of the Great Lakes, but much water remained in the sand below the surface, in surface depressions, as lakes, and as swamp remnants of the glacial lake.

Pure limestone is readily soluble and some of the Silurian limestones are pure lime. Water entered the cracks, dissolved the stone, made funnel-shaped depressions as it went dissolving down the joints, and made caves and caverns as it dissolved its way along the bedding planes. It made one cave above another with a thin cracked layer of stone between and the tops or roofs of the upper caves fell in, making funnel-shaped surface pits and hour-glass fashion carrying down the sands of the glacial drift through the cracks into the cave below. Two such caves

united below the surface, and their unsupported roofs collapsed making one oval depression loading to a crack in the floor. Waters from the lower cave bubbled up through the crack bringing a fountain of sands--lime, sand, shell fragments, and exquisitely formed microscopic shells of ostracods. The water-filled depression became a pool and vegetation gave its emerald color in reflection to the clear waters. The Big Spring was born. Dying and dead trees fell into the pool. Nature draped them with verdant mosses, making them eerie things of beauty in their watery graves. The Indians built their village Osawanimiki on the southeastern shore of Indian Lake and dreamed the legends of the wonder spring.

WHERE DOES THE WATER COME FROM?

The water at Kitch-iti-Kipi comes from fissures in the limestone bedrock at the bottom of the spring. Hydraulic pressure forces 10,000 gallons of spring water per minute to the surface at a constant temperature of 45°F year-round. The water's constant movement and recycling process help keep the spring from freezing, even in the coldest winters.

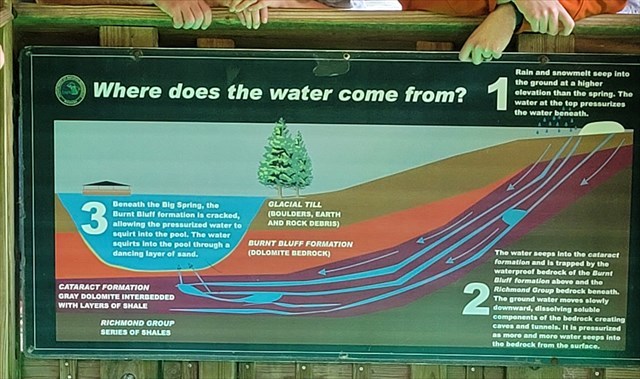

1: Rain and snowmelt seep into the ground at a higher elevation than the spring. The water at the top pressurizes the water beneath.

2: The water seeps into the cataract formation and is trapped by the waterproof bedrock of the Burnt Bluff formation above and the Richmond Group bedrock beneath. The ground water moves slowly downward, dissolving soluble components of the bedrock creating caves and tunnels. It is pressurized as more and more water seeps into the bedrock from the surface.

3: Beneath the Big Spring, the Burnt Bluff formation is cracked, allowing the pressurized water to squirt into the pool. The water squirts into the pool through a dancing layer of sand.

Sources:

https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/egle/Documents/Programs/OGMD/Catalog/04/GIMDL-GGKITCH.PDF?rev=4ee5117903ef474b8269922ee52fa4bb

https://www.inspirationaltraveladventures.com/legend-of-kitch-iti-kipi-near-manistique-michigan/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitch-iti-kipi

| I have earned GSA's highest level: |

|