| This cache has three locations

and four waypoints that you will need to locate. The material you

need to find the cache will be set like this text so that you can

skip all the history stuff if it doesn't interest you. If you

drive, this cache will probably take you less than an hour to

complete. If you walk, I'd allow about two hours. Church Hill has a

reputation in Richmond that greatly exceeds the reality. We spent a

great deal of time wandering the area looking for suitable

locations and never felt at risk in the slightest. I probably

wouldn't suggest going to the final cache location alone at night,

but otherwise you should be perfectly fine. In fact, the second

location offers one of the coolest views in the city at

night. |

In the years following the Civil War, the Shockoe Valley was the

hub of the city and trains were the key to commerce. When the

Chesapeake and Ohio railroad suggested a tunnel under Church Hill

would be the best way to go, Richmond's City Council came up with a

$300,000 bond in 1871. In February 1872, work started on the more

than half a mile long tunnel at both ends, with a force of more

than 400 men. This was the first effort to tunnel through

Richmond's many hills and there were many signs that the geology

wasn't well-suited to the attempts. In May, there were two separate

collapses in the vertical shafts dug to access the tunnels. By

January, cracks were appearing in the ground of Church Hill above

the tunnel. They became serious enough to evacuate residents on

January 13 and on January 14 a section between 24th and 25th

streets collapsed, ruining three houses and the Third Presbyterian

Church. In the end, the tunnel took almost a year longer than

expected and cost more than twice the original estimate.

Nonetheless, when it opened on December 11, 1873 it was hailed as

an engineering marvel and a great success. Until 1902, trains used

it as the regular route to the Main Street station. At that time,

the current route along the river on the high trestle (next to our

Ship, Lock and Key cache) was opened and the C&O stopped using

the tunnel. The primary reason for building this route was

apparently the delays in traffic when trains entered the tunnel at

the western portal. In 1913 the city extended the eastern end of

the tunnel, but serious efforts to reopen it didn't arrive until

1925.

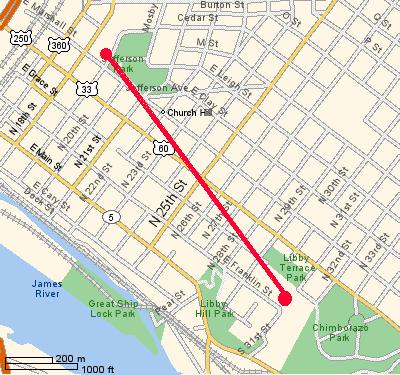

Map showing approximate path of the tunnel

C&O began serious efforts to repair and reopen the tunnel in

the Fall of 1925. In September, surface damage above the tunnel was

noted and railroad crews began inspecting and preparing the tunnel

to reopen. On October 2, 1925 engineer Thomas J. Moson drove a

locomotive pulling 10 flatcars nearly all the way through the

tunnel, parking around 100 to 150 feet from the western portal. As

workers were digging at the foundations, a brick or two rained down

from the roof. As the workman ran frantically to safety, the tunnel

collapsed completely burying Mason and crushing the train, sending

scalding steam in all directions. The fireman, Benjamin Mosby was

seriously burned by the steam, but managed to crawl under the train

and walk a mile or more to the other exit. Unfortunately, he died

in the hospital later than night. The conductor, G.C. McFadden,

escaped with a broken arm and the brakeman, C.S. Kelso suffered

head injuries. There is some controversy concerning the others

trapped in the collapse. C&O initially reported one

African-American laborer was unaccounted for and later amended the

list to two. One was Richard Lewis and the other was H. Smith.

There have been a variety of reports that claim variously that

Smith actually escaped and was later seen elsewhere or that as many

as 15 other African-Americans remain buried in the tunnel. Record

keeping was clearly not up to modern standards and most of the 200

or so laborers were hired day to day and no one really knows who

may have been trapped in the collapsed tunnel. A massive excavation

and rescue effort was halted once the body of Mason was located and

the rest of the collapsed section has never been excavated and

searched, so no one can say for sure.

| Proceed to the coordinates

posted for the cache. You will find yourself at the mouth of the

tunnel on the western end. You are probably facing a sign

memorializing the event above the entrance portal. On the (now

missing) sign, a section reads "75 years to this day". Call the

first digit A (7) and the second digit B (5). Proceed to the

entrance of the tunnel below and note that there is a year marked

on the tunnel mouth. Call that date CDEF. In other words, if the

date is 1987, C is 1, D is 9, E is 8 and F is 7. Your next waypoint

is 37° 3C.DFA 77° EB.(E+C)AB. You might reflect on the tragedy that

not only were these men not identified, but that their final

resting place has become a dump. If we each practice

cache-in/trash-out, maybe we can change that. |

If you like, you could walk 150 feet up the hill into the park

and stand near 37° 32.151 77° 25.374. That would be a spot very

close to where the train rests today directly under your feet. The

coordinates we've selected for the second location aren't quite

over the top of the tunnel, but it isn't far from it. It should

give you a very clear view of why the tunnel was needed. At the

point where you stand, the tunnel is about 100 feet below the

surface.

Proceed to the coordinates

noted in the first step. You should see another sign. Make a note

of the following numbers:

G = James River

H = Riverfront Towers

I = Main Street Station

J = Tyler Building

K = last digit of City Hall

LL = both digits of the Martin Luther King Bridge

The third location you need to go to is 37° HG.IKK 77°

LL.JKK |

You are now overlooking the other side of the tunnel. The train

tracks you see are essentially the same ones that were in place in

the 19th century. They just curved alongside the hill you are

standing on and went into the ground under the hill just to your

right. You can check your GPS to see how far you are from the first

location. It would have been a terrible walk in the dark after the

collapse of the tunnel. All of the men (variously reported as being

from 100 to 200 or more) who escaped from the collapse, escaped

this way.

The octagonal building you see to your left (as you face the

river!) also sits on a fairly well-known underground structure.

This is the site of a mid-1800s German brewery and they had six

massive brick vaults to store their beer buried just under the

building. The biggest vault is more than 500 square feet and they

have to be inspected periodically when they have earth slides here.

I am told there is no beer left.

As with almost any Richmond site, it is impossible to avoid

Civil War history. You are standing on the site of a large Southern

hospital during the war. It occupied 40 acres all around the area

where you stand. It could hold over 3,000 patients and treated more

than 76,000 during the war years. The mortality rate here was 10%

(some reports say 20%), which wouldn't make MCV very happy, but was

in fact quite extraordinary at the time. It was said to have been

the largest military hospital in the world at the time.

You are also loosely in the area of Powhatan's Seat, the

legendary home of the famous Indian leader who is perhaps best

known today as Pocahontas' father. There are interesting historical

markers along the ridge of this famous Hill.

| If you did this right, you

should be looking at another sign. Let the last two numbers on the

sign be MN. The last two digits of the first number on the sign

will be called OP. You will find the cache at 37° MG.NIM 77° LL.JPO

It should be a very short walk to the cache, but you'll probably

want to go down and around the octoganal building. Otherwise, you

might get to the cache a little faster than is safe. |

The way the cache is hidden is a bit of a joke. It is a very

common method, carried to a bit of an extreme. We may eventually

change it, but it amused us at the time.

Should you be interested, the other portal of the tunnel is

located near 77° 31.611 77° 24.892. You can continue on the trail

you took to the cache or you could start from the end of Franklin

Street (near 31st). The property is still owned by the railroad,

although clearly abandoned. It is an even more depressing dump than

the other portal. If you were especially adventurous and not too

concerned with the legal niceties, you might crawl through the hold

cut in the chain link fence into the tunnel itself. If you were

even more bold, you might find a place where you could crawl

through and go a surprisingly long way into the tunnel. Not that I

think it is a very good idea. I'd hate for it to collapse on

you.