This cache will take you to an old Dutch well on Tanjung Tuan.

Type of EarthCache: Permeability (Porosity).

The Old Dutch Well

Tanjung Tuan is home to at least four artesian wells. Three of these wells appear rather recent, they are similar in appearance and their walls are fully supported by concrete sections similar to those used for modern sewer systems. From these three, two are located fairly close to the Dutch well; one is located right across it, hidden under foliage mere metres away, the second is located near the footprint of Hang Tuah, with the third located on the southern end of the cape on Treasure Hunters Beach. For this cache, however, we focus on the oldest and most interesting well on the cape.

The Dutch arrived at Malaysia in early 17th century, and after a fierce battle wrested nearby Melaka from the Portuguese in 1641. They created outposts on several islands, and would have several people stationed at or near Tanjung Tuan as they sourced laterite from a nearby quarry to rebuild the fort in Melaka. This suggests the well might date back a respectable 380 years. However, it is not unthinkable that the Dutch merely upgraded a preexisting Portuguese well, in which case its age would increase significantly by about another 100 to 130 years. However, at the moment of writing there is no reason to assume the well predates the Dutch era.

This well was probably used to supply the people stationed here as well as supplying ships sailing through the Malacca Strait. It has long since lost its purpose and its age and years of neglect are clearly visible. However, despite everything it still functions perfectly, as if it was built yesterday, serving as a testament to the engineering skills of the time.

The old Dutch well is a classic example of an artesian well. If you are visiting after a spell of rain, you might be in for a treat. Though currently in desperate need of attention, the water remains very clear. If it were maintained would certainly be able to provide fresh and clean drinking water.

The 17th century Dutch well at Tanjung Tuan.

(Source: Barnyard Dawg, July 2017)

What is groundwater?

Ground water is simply water that is below the surface of the ground upon which we stand. One sees a source of ground water each time it rains. Often, the thought is that rain just provides life sustaining moisture to fauna and flora, the excess, however, filters down through the soil and rock.

What is an aquifer?

Groundwater drains through surface layers of soil and rock until it reaches a layer of material through which it cannot pass, or can pass only very slowly. This results in the accumulation of water in the rock layers above this impermeable layer. The water is stored in an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock, rock fractures or unconsolidated materials (gravel, sand, or silt) from which it can be extracted using a water well1. Simply put, the material that holds the water is an aquifer.

An aquifer may be as little as 30m from the surface, or as much as 300m. It costs more to pump water from the deeper aquifer but the water quality in the deeper one may be better than the shallower since contaminants, which the water may be carrying, are removed as the water moves through the rock. Historically, groundwater has been naturally very clean because of this filtering effect.

What is an artesian aquifer?

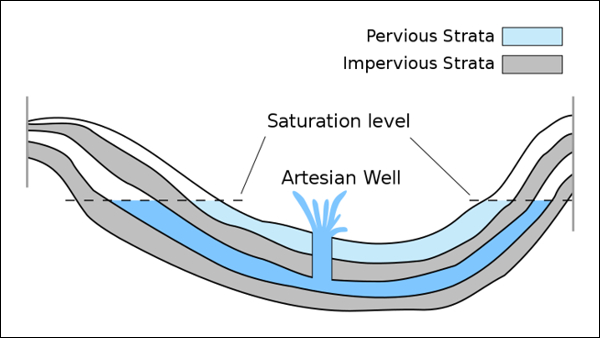

An artesian aquifer is a confined aquifer containing groundwater under positive pressure. This causes the water level in a well to rise to a point where hydrostatic equilibrium has been reached. A well drilled into such an aquifer is called an artesian well. If water reaches the ground surface under the natural pressure of the aquifer, the well is called a flowing artesian well2, 3. An artesian aquifer is confined between impermeable rocks or clay, which causes this positive pressure. Not all the aquifers are artesian (i.e. water table aquifers occur where the groundwater level at the top of the aquifer is at equilibrium with atmospheric pressure). The recharging of aquifers happens when the water table at its recharge zone is at a higher elevation than the head of the well.

An aquifer feeding a flowing artesian well.

How does an aquifer work?

An aquifer is filled with moving water and the amount of water in storage in the aquifer can vary from season to season and year to year. Ground water may flow through an aquifer at a rate of 50 feet per year or 50 inches per century, depending on the permeability. However, no matter how fast or slow, water will eventually discharge or leave an aquifer and must be replaced by new water to replenish or recharge the aquifer. Thus, every aquifer has a recharge zone or zones and a discharge zone or zones. For the Dutch well at Tanjung Tuan, the recharge zone(s) are located at higher altitudes.

The amount of water in storage in an aquifer is reflected in the elevation of its water table. If the rate of recharge is less than the natural discharge rate plus well production, the water table will decline and the aquifer's storage will decrease. A perched aquifer's water table is usually highly sensitive to the amount of seasonal recharge so a perched aquifer typically can go dry in summers or during drought years.

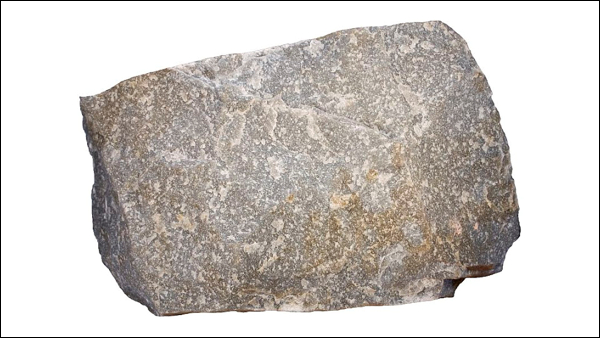

The underlying bedrock at this stretch of coast is metaquartzite, or simply quartz. Quartz is a rather impermeable rock unless highly fractured. It is however likely that the aquifer that serves the Dutch well is made up from metaquartzite fine gravels just below the surface, changing quickly into coarse metaquartzite gravels and cobbles, which provides a fairly high permeability. The Dutch well seems to have been placed ideally, as it has yet to run dry during prolonged dry spells. However, during the monsoon season, the aquifer reaches its saturation point quickly. As the old well is no longer in use, the lack of discharge from the well fails to relieve the pressure from the aquifer. The positive pressure on the aquifer results in excess groundwater being pushed out of the well and through the surrounding topsoil, allowing the formation of shallow pools in the immediate surrounding of the Dutch well (hence the slightly elevated wooden walkway).

Metaquartzite is greyish rock with only one dominating mineral — quartz.

Saltwater intrusion

Aquifers near the coast, such as the Dutch well, have a lens of freshwater near the surface and denser seawater under freshwater. If too much ground water is pumped near the coast, seawater may intrude into freshwater aquifers causing contamination of potable freshwater supplies. Seawater penetrates the aquifer diffusing in from the sea and is denser than freshwater. For porous (i.e., sandy) aquifers near the coast, the thickness of freshwater atop saltwater is about 12 metres (40 feet) for every 0.30 metres (1 foot) of freshwater head above sea level. This relationship is called the Ghyben-Herzberg equation4.

A fun optional experiment

For an easy practical example, I would like to invite you to continue down the path from the Dutch well and proceed to the beach. The beach will provide a model to help visualize an aquifer. You might recognise what will happen next if as a child you have spent some time digging holes on the beach. For this example, stand near the waterline and dig a hole in the sand. Very wet or saturated sand will be located at a shallow depth. The hole acts as a crude well, the wet sand represents an aquifer, and the level to which the water rises in this hole represents the water table.

How to claim this EarthCache?

Send me the following;

1. The text "GC7C74V The Old Dutch Well" on the first line.

2. The answers to the following questions;

- Why is groundwater so clean?

- Do you consider the Dutch well to be an artesian well or a flowing artesian well?

- Knowing how the well behaves during the monsoon season, what does this tell you about the speed of the recharge process, and in extension the size and composition of the aquifer?

- How can you quickly tell the difference between permeable and impermeable rock?

3. Provide a photo of yourself or a personal item to prove you have visited the site.*

References

1 FWR, Foundation For Water Research, UK. 2 Wheeler, H. W (1980), Artesian bores of South Australia: an annotated photographic record, 1939-1948. 3 Federal Water Resources Assistance Program (Australia); New South Wales. Department of Water Resources. Technical Services Division; Australian Water Resources Council. Interstate Working Group on the Great Artesian Basin (1990), Specification for construction, reconditioning or plugging of bores tapping recognised aquifers of the Great Artesian Basin in New South Wales (1st ed.), Dept. of Water Resources, Technical Services Division. 4 Verrjuit, Arnold (1968). "A note on the Ghyben-Herzberg formula" (PDF). Bulletin of the International Association of Scientific Hydrology. Delft, Netherlands: Technological University. 13 (4): 43–46. Retrieved 2009-03-21. A Idaho State University, USA.

* Effective immediately from 10 June 2019, photo requirements are permitted on EarthCaches. This task is not optional, it is an addition to existing logging tasks! Logs that do not meet all requirements posed will no longer be accepted.

For additional information, visit; Geosociety.org, Geocaching.com Help Center and Geocaching.com Forum.

Finding the answers to an EarthCache can often be challenging, and many people tend to shy away from these caches because of this. However, it is my opinion that geocaching is also meant to be a fun family experience that simply aims to introduce interesting and unique locations such as this one. Flexibility on logging requirements, however, can only be applied if it can be established that you have actually taken the time to visit the site. For this reason, a proper log describing your adventure accompanied by a good number of photos would be much appreciated.

Join us at Geocaching Malaysia