Notice: "Cache seekers assume all risks and responsibilities involved in seeking this earthcache." “Just because it is there, doesn’t mean you have to seek the cache!” Don’t let earthcaching control you, but rather you control earthcaching.

Kennewick: Granodiorite

Much of the rocks which underlie the Tri-Cities, the Columbia basin and plateau is basalt laid down between 6-17.5 million years ago from volcanic fissures in Southeast Washington. These basalt flows are part of the Columbia River Basalt Group.

There are some rocks scattered throughout the sloping hills set within the loess soil that are not native to this area. They vary in size from pebbles to large boulders. They are mostly granitic in nature. There are literally thousands of these ice rafted granitic rocks found on the Iowa Flats between the east side of Rattlesnake Ridge and Washington County Road 240 and just north of the Rattlesnake Mountain Shooting Facility on WA CO RD 225. (See Earthcache: Rattlesnake Mountain: Red Rock Ravine GCA1MDC )

While driving around the anticline hills of Kennewick, Richland and step of the Horse Heaven Hills, these isolated granitic boulders may be spotted. They are especially easy to spot after grass wildfire. Most of them are on private property. These rocks were moved here during the devastating ice age floods between 13-15,000 years ago from northern Idaho part of the Kaniksu Batholith.

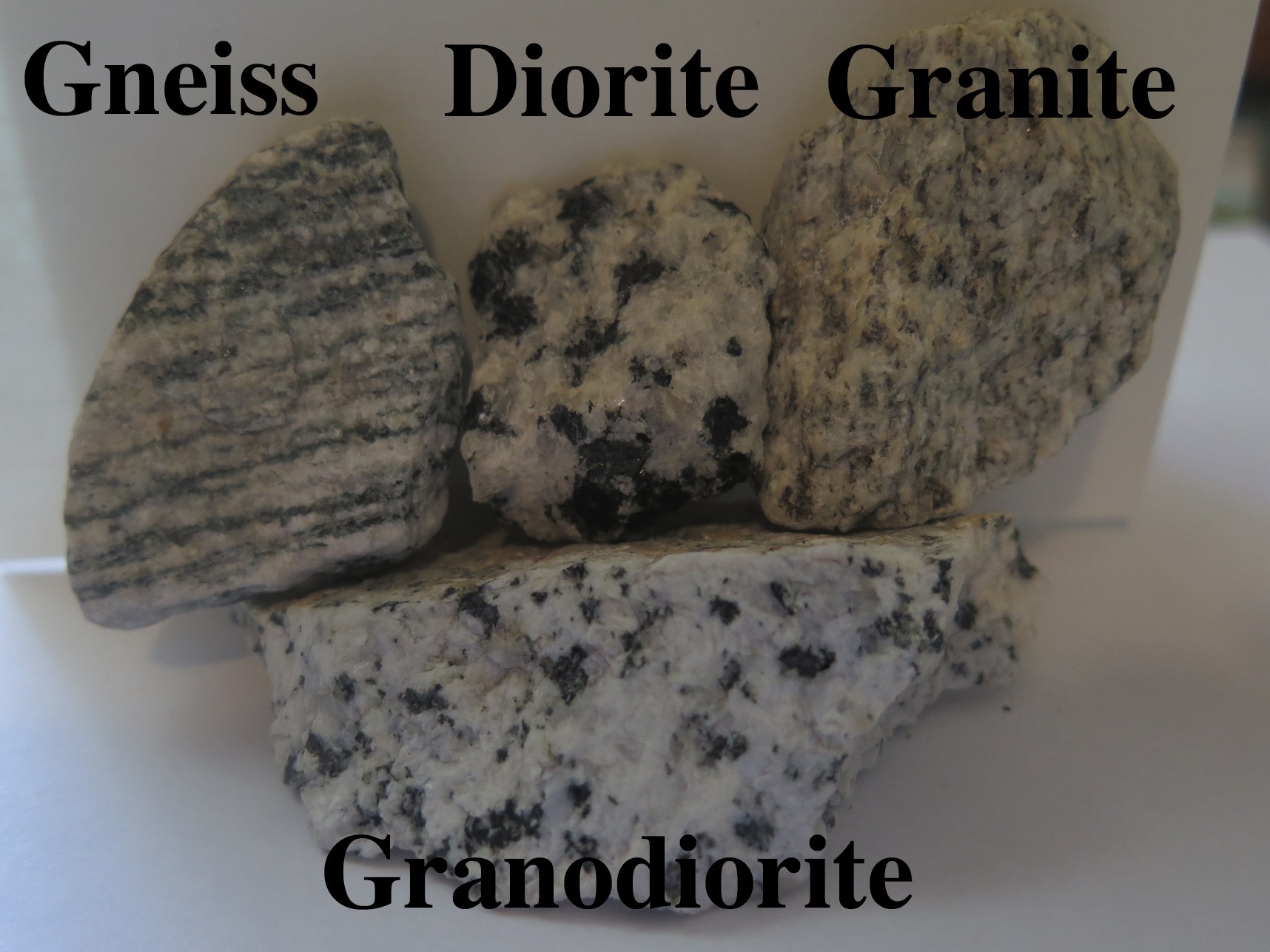

With some exceptions, most of the isolated boulder in the Tri-Cities area are granite and granodiorite. There is some gneiss and diorite.

Photo of Granite taken at Granite Point on the Snake River, Northwest of Clarkston, Washington

Granite rocks are intrusive (hot melted magma which slowly cools) that was extruded from below the surface of the earth during the Cretaceous era. Granite contains mostly quartz (Silica) with feldspar (Alumina) and Plagioclase (Sodium and Calcium).

Photo of Newman Lake Gneiss taken at Minnehaha Climbing Wall, Upriver Drive, Spokane, Washington

Gneiss (pronounced “nice”) rocks are metamorphic (forms without completely melting) with a similar make up of granite but because of the extremely high temperature and pressure deep below the earth surface bands within the rock are created. Gneiss is also made up of quartz, feldspar, along with mica (Biotite: Iron and Magnesium which forms sheets) and amphibole (Hornblende a mixture of silica, aluminum, calcium, and sodium).

Photo of Granodiorite taken outside of the “Museum at Keewaydin” Kennewick, Washington

Granodiorite rocks are also igneous, formed by intrusion with silica rich magma and cools in batholites below the earth surface. With erosion granodiorite batholites are exposed. Granodiorite is made up of quartz, feldspar, biotite, and hornblende.

Photo of small Diorite sample taken from Columbia River, Kennewick, Washington

Diorite is a coarse-grained igneous rock created by slow cooling magma. Diorite is made up of silica, feldspar, hornblende and biotite.

Identification of minerals within Granitic Rocks: In general, clear Quartz crystals in rock samples in sunlight are reflective whereas other quartz is dull. Both Hornblende and Biotite are black in color. Hornblende is dull and softer than Biotite which is harder, shiny and layered in sheets. Titling the rock sample back and forth with sunlight will reveal biotite reflectivity. Potassium feldspar (light pink) or Plagioclase feldspar (white) are dull and non-reflective.

How to Identify: granite, gneiss, granodiorite and diorite

Gneiss is the easiest to spot. Just look for banding. These bands are dark and made up of biotite and hornblende.

Diorite is also easy to spot. Just look for large coarse grained hornblende spots.

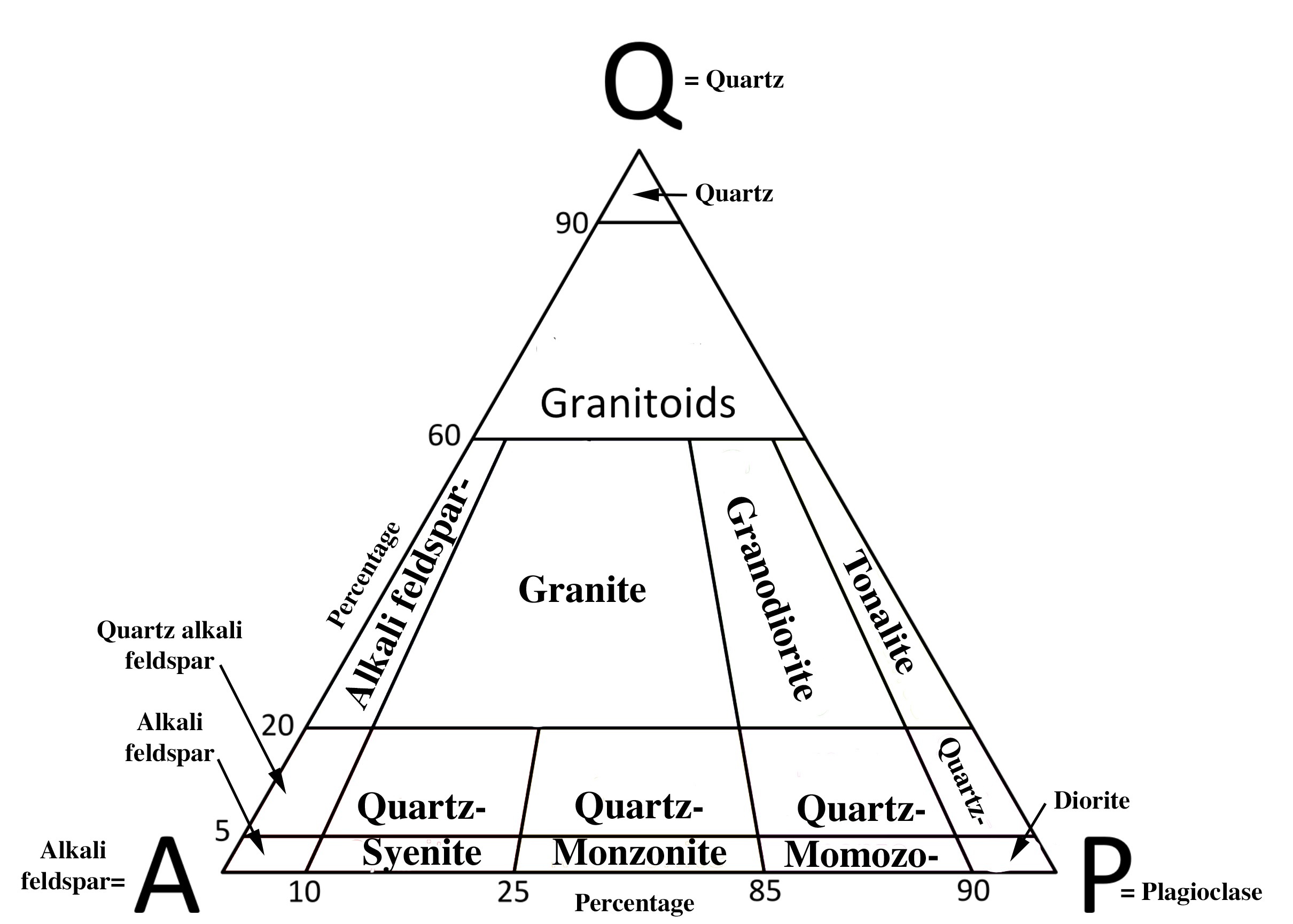

Granite and Granodiorite: Figuring out the difference between granite and granodiorite is a little harder and in some cases a microscope is needed or chemical and x-ray examination must be done to determine which kind of rock it is. The upper portion of a “QAPF” (Quartz, Alkali Feldspar, Plagioclase, and Feldspathoids) diagram may also be helpful in the identification. In general, but not always true, granite has more potassium feldspars which is a light salmon pink color. Granodiorite has more plagioclase and tends to have more peppered specks of hornblende and biotite.

QAPF Diagram

This is a simplified upper portion of a QAPF Diagram

Study the diagram. The diagram represent the percentage amount of Quartz, Alkali Feldspar, Plagioclase that each classified rock contains. Moving right, left or up the chart, the amount of minerals contained in each rock increases. First, notice Gneiss is not on the chart because it is a metamorphic rock and this chart is for intrusive-igneous-plutonic rocks. Second, notice Diorite is down in the bottom right-hand corner and contains lots of plagioclase. Lastly, notice where granite and granodiorite are located right next to each other in the center. This is why as both rock move to the middle of the diagram, it becomes extremely difficult to identify them visually. When it doubt, just call the sample a granitoid.

Granitic Rock Samples from the Columbia River, Kennewick, Washington

The traffic circle at West Tenth Avenue and South Steptoe St. (formerly Clofelter Rd.) contains 9 granodiorite boulders. These boulders were removed from the hillside some 500 feet south of the roundabout. They most likely ice rafted to this location during the ice age floods from Montana or northern Idaho13-15,000 years ago. These boulders are light in color with small peppered specks of hornblende and biotite. These boulders are the same as the one found outside the “Museum at Keewaydin” Park at Reference Point 1.

To Log this Earthcache

Step 1: Travel to Reference Point 1 located outside the “Museum at Keewaydin” Park. 205 West Keewaydin Drive, Kennewick, WA. There you will see a plaque dedicated to the Kennewick Man, native American petroglyphs and a granodiorite boulder and its signage. This granodiorite boulder is of the same classification as the granodiorite boulders you will find at the final. Take time to inspect the granodiorite boulder here because at the final you will not be able to get a close-up view. If possible, take a close-up photo of the grain structure and the sign information for future reference.

Step 2: Travel to designated parking area south of the final posted coordinate, using the crosswalks make your way around the traffic circle to the northeast knoll and walk up to the view point of the earthcache and the 9 granodiorite boulders. At the final, take note of the two large darken basalt boulders and a light-colored granitic boulder.

Safety Note: Do not access the center circle of the roundabout. This earthcache is not in the roundabout. All observation are made from the knoll which overlooks the roundabout and is easily accessible via the cross walks from the parking area. Please use common sense. The best time to find this earthcache is mid-morning or mid-afternoon and not during morning or late afternoon-evening rush hour.

Step 3: Please send me the answers to the following questions via email or the geocaching.com message center.

1. At reference point one, where does the sign say the granodiorite was originally located?

2. What is the main difference between a granite and granodiorite rock?

3. What is the difference between a rock that is intrusive and one that is metamorphic?

4. Using the photos, diagram on this earthcache page and your observation at Reference Point I, identify the light-colored granitic boulder at the final posted coordinate.

Optional: You may upload a photo to the page of any local wildlife, unique vegetation or geology in the area.

Additional study and sources:

QAPF Diagram of Classification of Igneous Rocks

What Experts Will Tell You about Granodiorite Rock

Diorite: Composition, Properties, Occurrence, Uses

Granite and Granodiorite FAQ

Granite vs Gneiss: The Difference Between Gneiss and Granite

Digital Geology of Idaho